Origins and Beginnings PART 1

The Two Texts of Ethelbert [1]

When we think of origins and beginnings in relation to Textus Roffensis, the obvious place to start is with the two texts connected to King Ethelbert of Kent: his law code and his foundation charter for the church at Rochester. The law code (which you can read in translation at the end of part 1) is now positioned as the opening text of our medieval book, though it was not so originally. The charter introduces us to the book’s cartulary (its collection of charters); its beautiful decorated initial would have been the first thing to greet the reader when the cartulary was originally a separate volume. (I explore the charter in part 2 of 'Origins and Beginnings'.)

The idea of origins is, however, far more than a matter of where these two texts appear in the codex. The law code of Ethelbert, dated to about the year 600, is the earliest English text in existence! Its writing marks the very moment English became a language of the book. It is Textus Roffensis alone which captures this historic event, preserving as it does the only extant copy of the document. Moreover, Ethelbert’s law should be understood more broadly as the document that sets the foundation for English law and society. Though arguably a relatively unsophisticated set of rules when compared to later Anglo-Saxon law codes, it is fundamentally important in helping us to understand society and culture in the earliest stages of English history.

The relationship of Ethelbert’s foundation charter to the concept of origins is perhaps a more complex one, for this document is a forgery or, more precisely, a copy of a forgery. Though it purports to have been originally written by Ethelbert in the year 604, experts today are in no doubt that the charter is a fabrication; indeed, one scholar has recently made the case that charters were not introduced into England until 670.[2]

The foundation charter’s dubious heritage should not, however, put us off from exploring its association with the idea of beginnings and origins. In fact, when we take a close look at the document, examining it both textually and visually, we can begin to appreciate how vital it must have been for the bishop and monks of Rochester to assert their claim to an ancient genesis for their church.

First, however, let us explore in greater detail the story behind Ethelbert and his law code. What do we know about this early English king? And why was it so important to get his law into writing?

When we think of origins and beginnings in relation to Textus Roffensis, the obvious place to start is with the two texts connected to King Ethelbert of Kent: his law code and his foundation charter for the church at Rochester. The law code (which you can read in translation at the end of part 1) is now positioned as the opening text of our medieval book, though it was not so originally. The charter introduces us to the book’s cartulary (its collection of charters); its beautiful decorated initial would have been the first thing to greet the reader when the cartulary was originally a separate volume. (I explore the charter in part 2 of 'Origins and Beginnings'.)

The idea of origins is, however, far more than a matter of where these two texts appear in the codex. The law code of Ethelbert, dated to about the year 600, is the earliest English text in existence! Its writing marks the very moment English became a language of the book. It is Textus Roffensis alone which captures this historic event, preserving as it does the only extant copy of the document. Moreover, Ethelbert’s law should be understood more broadly as the document that sets the foundation for English law and society. Though arguably a relatively unsophisticated set of rules when compared to later Anglo-Saxon law codes, it is fundamentally important in helping us to understand society and culture in the earliest stages of English history.

The relationship of Ethelbert’s foundation charter to the concept of origins is perhaps a more complex one, for this document is a forgery or, more precisely, a copy of a forgery. Though it purports to have been originally written by Ethelbert in the year 604, experts today are in no doubt that the charter is a fabrication; indeed, one scholar has recently made the case that charters were not introduced into England until 670.[2]

The foundation charter’s dubious heritage should not, however, put us off from exploring its association with the idea of beginnings and origins. In fact, when we take a close look at the document, examining it both textually and visually, we can begin to appreciate how vital it must have been for the bishop and monks of Rochester to assert their claim to an ancient genesis for their church.

First, however, let us explore in greater detail the story behind Ethelbert and his law code. What do we know about this early English king? And why was it so important to get his law into writing?

Ethelbert according to Bede

Our best source of historical detail about Ethelbert is the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum) written by the Father of English history, Bede. [3] Though Bede is generally a reliable historian it is important to remember that his account, as with all historical narratives, is written from a particular angle or perspective, in this case one that emphasises the spiritual over the political.

The story of Ethelbert is used by Bede as a dramatic apostolic narrative: the king’s conversion by the missionary monk Augustine, sent by Pope Gregory the Great, is conceived of as the sprouting and blossoming of English Christianity. Ethelbert’s political motives are not Bede’s (nor should they be his readers’) chief concern, though it is possible to glean from Bede’s cited sources, principally letters from the pope, that something more than the spreading of the gospel was a driving force for the king.

Perhaps the best note of caution sounded for readers of Bede’s conversion narrative is that by the historian Nick Higham who reminds us that ‘Bede’s story of an English nation eager for conversion by Roman missionaries is both simplistic and overly optimistic’.[4] We must remember, too, that the Ecclesiastical History was completed about the year 731, more than a century after Ethelbert’s death around 616 and is heavily reliant on Bede's Canterbury contemporary, Abbot Albinus, with whom Bede shared a great deal of interest in Rome and the Gregorian mission.

These circumstances should prompt us to interpret Bede’s story of Ethelbert with a degree of caution. It is, nevertheless, helpful to see what Bede did write about King Ethelbert of Kent, and in doing so we may gain an insight into why he produced England’s first set of written laws.

Ethelbert’s reign over the Kentish folk was summed up by the venerable monk and scholar as ‘a glorious earthly reign of fifty-six years’, finishing at his death in the year 616, though there is considerable doubt over his reign being that long.[5] It may be that Bede is conflating his total years on earth with his years as king.

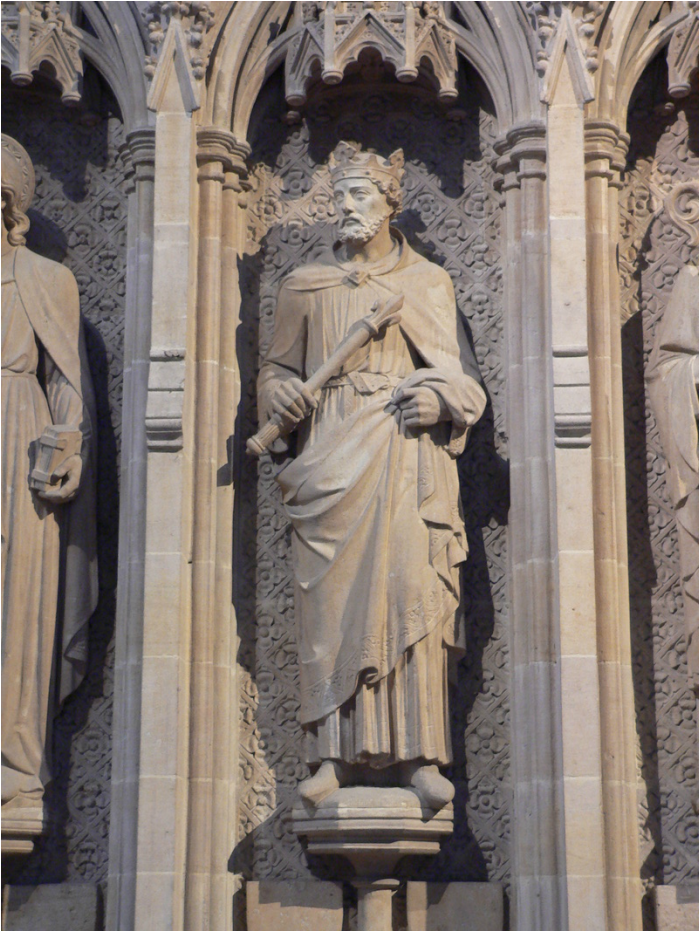

Though we typically refer to Ethelbert as a king of Kent, he was in reality overlord of a much larger area of England. Bede informs us that ‘He was the third English king to hold sway over all the provinces south of the river Humber’, adding with passion, ‘but he was the first to enter the kingdom of heaven’![6] Bede’s self-conscious prioritising of the spiritual over the worldly is actually key to understanding not only Ethelbert’s place in history but the importance of the two Ethelbert texts in Textus Roffensis. It is his position as the first Christian king in England that is most relevant when we consider the importance of his contribution to the evolution of both England and Englishness.

Our best source of historical detail about Ethelbert is the Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Historia ecclesiastica gentis anglorum) written by the Father of English history, Bede. [3] Though Bede is generally a reliable historian it is important to remember that his account, as with all historical narratives, is written from a particular angle or perspective, in this case one that emphasises the spiritual over the political.

The story of Ethelbert is used by Bede as a dramatic apostolic narrative: the king’s conversion by the missionary monk Augustine, sent by Pope Gregory the Great, is conceived of as the sprouting and blossoming of English Christianity. Ethelbert’s political motives are not Bede’s (nor should they be his readers’) chief concern, though it is possible to glean from Bede’s cited sources, principally letters from the pope, that something more than the spreading of the gospel was a driving force for the king.

Perhaps the best note of caution sounded for readers of Bede’s conversion narrative is that by the historian Nick Higham who reminds us that ‘Bede’s story of an English nation eager for conversion by Roman missionaries is both simplistic and overly optimistic’.[4] We must remember, too, that the Ecclesiastical History was completed about the year 731, more than a century after Ethelbert’s death around 616 and is heavily reliant on Bede's Canterbury contemporary, Abbot Albinus, with whom Bede shared a great deal of interest in Rome and the Gregorian mission.

These circumstances should prompt us to interpret Bede’s story of Ethelbert with a degree of caution. It is, nevertheless, helpful to see what Bede did write about King Ethelbert of Kent, and in doing so we may gain an insight into why he produced England’s first set of written laws.

Ethelbert’s reign over the Kentish folk was summed up by the venerable monk and scholar as ‘a glorious earthly reign of fifty-six years’, finishing at his death in the year 616, though there is considerable doubt over his reign being that long.[5] It may be that Bede is conflating his total years on earth with his years as king.

Though we typically refer to Ethelbert as a king of Kent, he was in reality overlord of a much larger area of England. Bede informs us that ‘He was the third English king to hold sway over all the provinces south of the river Humber’, adding with passion, ‘but he was the first to enter the kingdom of heaven’![6] Bede’s self-conscious prioritising of the spiritual over the worldly is actually key to understanding not only Ethelbert’s place in history but the importance of the two Ethelbert texts in Textus Roffensis. It is his position as the first Christian king in England that is most relevant when we consider the importance of his contribution to the evolution of both England and Englishness.

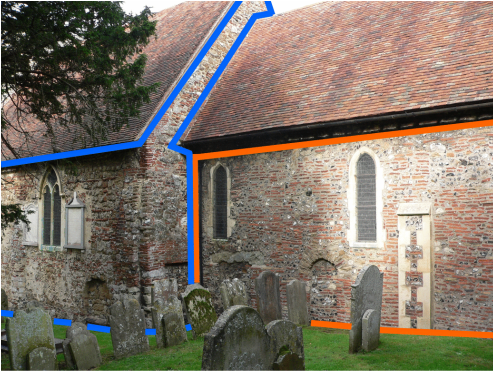

Even before the arrival of the Christian mission to England in 597, led by Augustine under the direct authority of Pope Gregory, Ethelbert was no stranger to Christianity. His wife Bertha, a Merovingian Frankish princess, was a devout Christian at the time of their marriage. According to Bede, her parents – and probably Bertha herself – laid down the prenuptial condition that Bertha would ‘have freedom to hold and practise her faith unhindered’.[7] Bede informs us that the parents had arranged Bishop Liudhard to travel with her to Kent, where he would serve ‘as her helper in the faith’, her personal chaplain.[8] Ethelbert fulfilled his promise, granting the use of the ‘old church’ in Canterbury, which had been dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours during the time of the Roman occupation of Britain.[9] Thus renovated, St Martin’s became Bertha’s private chapel, and subsequently Ethelbert, though not adopting his wife’s faith, was exposed to this new religion of hers.

Bede’s account of Ethelbert’s conversion reads like one of the mini dramas from The Acts of the Apostles. It is a narrative designed to show how a truly noble ruler, even though a heathen, will inevitably be won over by the comforting and edifying message of Christianity.

And so it was that Augustine, apostle of the English, along with forty fellow brothers in Christ, arrived in Ethelbert’s realm. Thanet, at the north-eastern tip of Kent, is the precise landing point provided by Bede. In Ethelbert’s time, it was an island separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, and thus it happens to work well, for Bede’s dramatic purposes, as a metaphor for the king’s initial distrust of his monk visitors.

Go to: MAP: KENT AT THE COMING OF THE SAXONS

Ethelbert’s response to the pope’s men is best described as one of watchful hospitality, for the translators whom Augustine sent to meet the king were told to remain and wait on the island where they had landed, and that their necessities would be met there.

Despite, then, his wife being Christian, or rather perhaps because he was more immediately familiar with Frankish churchman rather than the more distant authority of Rome, Ethelbert is depicted as peculiarly wary of these servants of Christ. So much so that Bede has the king, on arriving some days later on Thanet, holding his meeting with the missionaries out of doors to counter any attempts by them to overpower him with ‘magical arts’.[10]

In order to soothe the king’s anxieties, Augustine’s team deployed its best suite of audio-visual effects, approaching Ethelbert with a shining silver cross as their standard along with a painting of the Lord and Saviour himself, whilst also singing a petition to God in liturgical Latin. It seemed to do the trick, for Ethelbert commanded them to sit and preach to him and his court.

The words of the gospel clearly had an impact on the king, great enough to mollify any courtly bent toward pre-emptive violence against the magic-practicing missionaries, though not sufficiently powerful for Ethelbert to hand himself over to Augustine there and then for baptism. On the contrary, Bede records the king’s declaration that though the missionaries’ words and promises were fair indeed, they were also rather new and uncertain, and for that reason, we are told, Ethelbert also proclaimed, “I cannot accept them and abandon the age-old beliefs that I have held together with the whole English nation”.[11] A slightly stubborn Pagan, it would seem.

Nonetheless, Ethelbert proved to be a truly hospitable fellow. Perceiving Augustine’s sincerity, he promised the monks not to harm them and even granted them a house in his chief city of Canterbury, where not only would they be supplied with all their physical needs, but their desire to preach and convert would not be interfered with.

Bolstered by the king’s kindness, Augustine led his team into Canterbury, still bearing the silver cross and the painting of Christ, but now, according to a tradition rehearsed by Bede, singing a litany that petitioned the Lord to withhold his wrath and anger from the city and his holy house. Perhaps it was a wise move to sing in Latin.

It was the manner of life that the missionaries adopted in Canterbury that made the greatest impact on those to whom they preached. Emulating the life of the apostles and the primitive Church – not abusing the hospitality of their host city – Augustine and his brothers soon won over ‘a number of the heathen’ who admired the simplicity of their holy way of life.[12] Before long, the comforting message of Christianity moved these heathens to belief and baptism, and to sharing with their queen in worship at the church of St Martin’s.

Add to the mix of exemplary life and ‘gladdening promises’ of these holy men the performing of ‘many miracles’, and it comes as no surprise that, with the passing of time, Ethelbert and others were edified and prompted to accept the new faith and get baptized.[13] Once that happened, according to Bede, ‘great numbers gathered each day to hear the word of God, forsaking their heathen rites and entering the unity of Christ’s holy Church as believers’.[14]

Bede reports that it was said that Ethelbert did not compel his people to accept Christianity, having learned from his instructors that the service of Christ must be entered upon freely. Though if we accept the claims within one of Pope Gregory’s letters, that as many as ten thousand accepted the faith, then it’s quite possible that the peer pressure among the Kentish folk to take on the king’s faith may have been pronounced.

What the king did do, quite clearly, was promote Christianity. ‘It was not long,’ continues Bede, ‘before he granted his teachers in his capital of Canterbury a place of residence appropriate to their station, and gave them possessions of various kinds to supply their wants.’[15] And it was not long before Pope Gregory appointed Augustine as the first archbishop of Canterbury – in the same year as the mission arrived, in fact (597) – and in turn Augustine, with the king’s support, founded in Canterbury both his cathedral of Christ Church and the renowned St Augustine’s monastery which became a centre for great learning.

For Ethelbert, had the success of the Roman mission created an impact beyond the spiritual, beyond his personal conversion? It would seem so. In Augustine, a lettered man and biblical scholar, there stood an embodiment of Roman knowledge, wisdom and authority. He brought with him the vehicle to increased prestige and even the prospect of immortalisation. For not only did the Roman mission establish a new belief system in his realm, but it also brought to the English a new technology: writing!

And so it was that Augustine, apostle of the English, along with forty fellow brothers in Christ, arrived in Ethelbert’s realm. Thanet, at the north-eastern tip of Kent, is the precise landing point provided by Bede. In Ethelbert’s time, it was an island separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel, and thus it happens to work well, for Bede’s dramatic purposes, as a metaphor for the king’s initial distrust of his monk visitors.

Go to: MAP: KENT AT THE COMING OF THE SAXONS

Ethelbert’s response to the pope’s men is best described as one of watchful hospitality, for the translators whom Augustine sent to meet the king were told to remain and wait on the island where they had landed, and that their necessities would be met there.

Despite, then, his wife being Christian, or rather perhaps because he was more immediately familiar with Frankish churchman rather than the more distant authority of Rome, Ethelbert is depicted as peculiarly wary of these servants of Christ. So much so that Bede has the king, on arriving some days later on Thanet, holding his meeting with the missionaries out of doors to counter any attempts by them to overpower him with ‘magical arts’.[10]

In order to soothe the king’s anxieties, Augustine’s team deployed its best suite of audio-visual effects, approaching Ethelbert with a shining silver cross as their standard along with a painting of the Lord and Saviour himself, whilst also singing a petition to God in liturgical Latin. It seemed to do the trick, for Ethelbert commanded them to sit and preach to him and his court.

The words of the gospel clearly had an impact on the king, great enough to mollify any courtly bent toward pre-emptive violence against the magic-practicing missionaries, though not sufficiently powerful for Ethelbert to hand himself over to Augustine there and then for baptism. On the contrary, Bede records the king’s declaration that though the missionaries’ words and promises were fair indeed, they were also rather new and uncertain, and for that reason, we are told, Ethelbert also proclaimed, “I cannot accept them and abandon the age-old beliefs that I have held together with the whole English nation”.[11] A slightly stubborn Pagan, it would seem.

Nonetheless, Ethelbert proved to be a truly hospitable fellow. Perceiving Augustine’s sincerity, he promised the monks not to harm them and even granted them a house in his chief city of Canterbury, where not only would they be supplied with all their physical needs, but their desire to preach and convert would not be interfered with.

Bolstered by the king’s kindness, Augustine led his team into Canterbury, still bearing the silver cross and the painting of Christ, but now, according to a tradition rehearsed by Bede, singing a litany that petitioned the Lord to withhold his wrath and anger from the city and his holy house. Perhaps it was a wise move to sing in Latin.

It was the manner of life that the missionaries adopted in Canterbury that made the greatest impact on those to whom they preached. Emulating the life of the apostles and the primitive Church – not abusing the hospitality of their host city – Augustine and his brothers soon won over ‘a number of the heathen’ who admired the simplicity of their holy way of life.[12] Before long, the comforting message of Christianity moved these heathens to belief and baptism, and to sharing with their queen in worship at the church of St Martin’s.

Add to the mix of exemplary life and ‘gladdening promises’ of these holy men the performing of ‘many miracles’, and it comes as no surprise that, with the passing of time, Ethelbert and others were edified and prompted to accept the new faith and get baptized.[13] Once that happened, according to Bede, ‘great numbers gathered each day to hear the word of God, forsaking their heathen rites and entering the unity of Christ’s holy Church as believers’.[14]

Bede reports that it was said that Ethelbert did not compel his people to accept Christianity, having learned from his instructors that the service of Christ must be entered upon freely. Though if we accept the claims within one of Pope Gregory’s letters, that as many as ten thousand accepted the faith, then it’s quite possible that the peer pressure among the Kentish folk to take on the king’s faith may have been pronounced.

What the king did do, quite clearly, was promote Christianity. ‘It was not long,’ continues Bede, ‘before he granted his teachers in his capital of Canterbury a place of residence appropriate to their station, and gave them possessions of various kinds to supply their wants.’[15] And it was not long before Pope Gregory appointed Augustine as the first archbishop of Canterbury – in the same year as the mission arrived, in fact (597) – and in turn Augustine, with the king’s support, founded in Canterbury both his cathedral of Christ Church and the renowned St Augustine’s monastery which became a centre for great learning.

For Ethelbert, had the success of the Roman mission created an impact beyond the spiritual, beyond his personal conversion? It would seem so. In Augustine, a lettered man and biblical scholar, there stood an embodiment of Roman knowledge, wisdom and authority. He brought with him the vehicle to increased prestige and even the prospect of immortalisation. For not only did the Roman mission establish a new belief system in his realm, but it also brought to the English a new technology: writing!

Immortalising the law maker

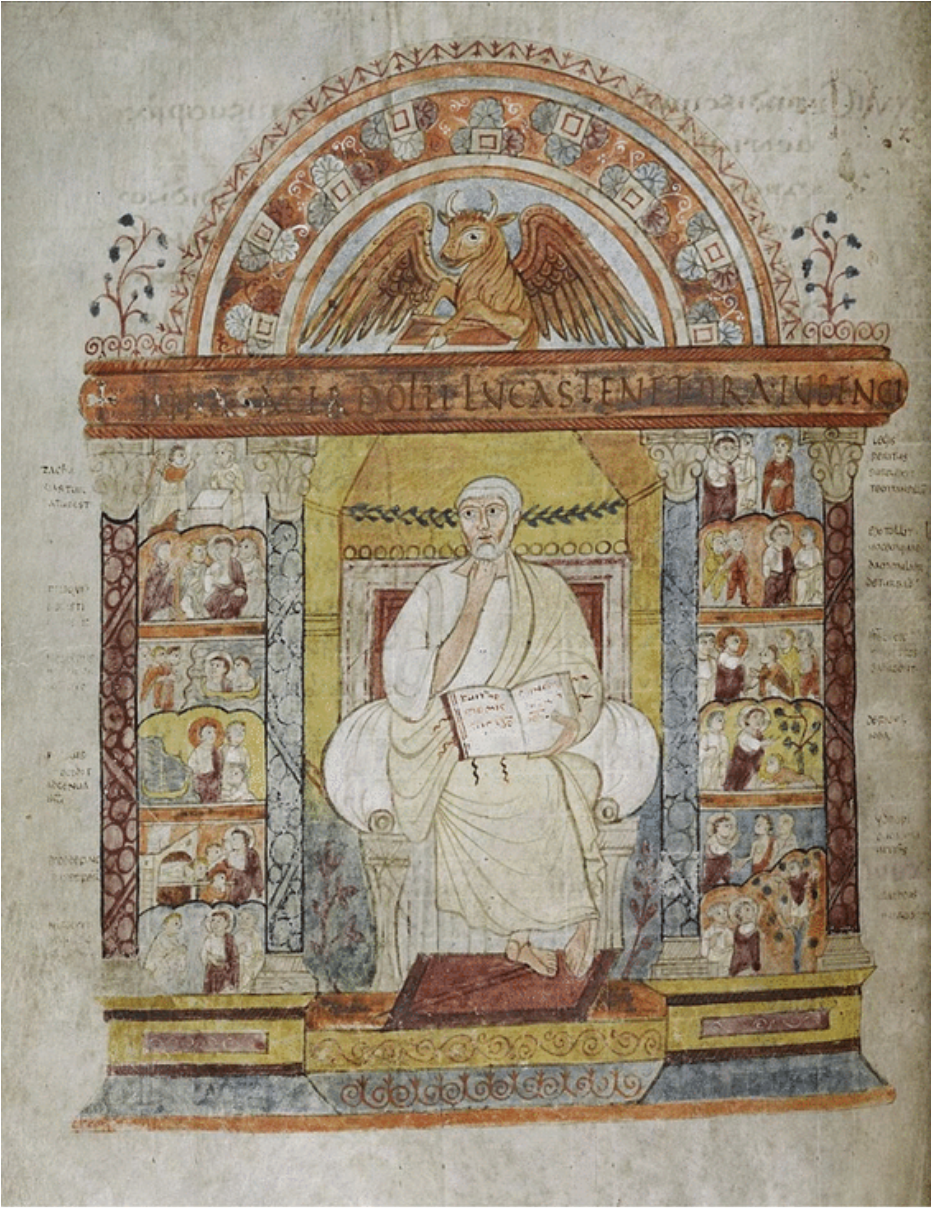

Christianity is a religion of the book. This would have been vividly impressed upon Ethelbert when he looked upon the splendidly illuminated gospel book, known today as the St Augustine Gospels, which the missionaries probably brought with them from Rome (see image above).

This treasure has survived more than 1,400 years and is still used today at Canterbury Cathedral as part of the enthronement ceremony for archbishops. I imagine Ethelbert feeling the heft of the book, carefully turning its calf-skin pages, being captivated by the workings of the pen, enthralled by the gold and the spectrum of colours within its narrative scenes and evangelist portraits. Unfortunately for us, only one of the four portraits survive, that of Luke, but it is this very image that may well have held great import for this English king.

Impossible as it is to know exactly what Ethelbert felt, it is nevertheless a powerful image: Luke, the writer about this new god, Christ, sits on an elegant throne, surrounded by exquisite architectural framing, contemplative like a philosopher and, most intriguingly, holding a book. Written words are thus intrinsically intertwined with the regal and the wise. Authority is written. Words, it seems, live forever on the page.

We have no way of knowing exactly the path of inspiration that lead to Ethelbert’s creation of a written law code, but evidently the stimulus was at least in part external. Bede, after acknowledging that the king’s own wisdom conferred many benefits on the nation, highlights Ethelbert’s code of law as the outstanding example of this, and suggests too that the king was ‘inspired by the example of the Romans’.[16]

By this Bede may have meant Ethelbert was motivated to imitate Roman law, though in fact, there is little resemblance in the structure and content of Ethelbert’s code that would indicate this was the king’s direct concern. Rather, I would suggest that Bede simply meant that Ethelbert wanted to be like the Romans in having a written system of laws, and that this would elevate him and his kingdom beyond those rulers, past and present, who relied solely upon oral tradition. In having his law code written down, Ethelbert was staking his claim to Romanitas; in having it written in English, he was also asserting the validity of his own world.

For Ethelbert, the inspiration for the Roman way of doing things is most directly traceable to those men who had travelled to his kingdom from Rome, Augustine and the rest of the missionary delegation, whom of course he met face to face. However, the influence of the pope in Rome should not be underestimated.

Ethelbert’s motivations for writing his laws down can be at least intimated from the contents of the letter he received from Pope Gregory within a few years of his baptism. Appealing to Ethelbert as a glorious ruler over ‘the English nation’, Gregory urged the king to extend the Christian Faith among his people, following the example of Emperor Constantine who ‘in his day turned the Roman State from its ignorant worship of idols’ to submission to Christ.

The rewards for Ethelbert would ultimately, of course, be heavenly, but Gregory made it equally clear that his earthly majesty was also at stake. Constantine’s ‘glorious reputation has excelled that of all his predecessors’, the pope expounds, ‘and he has outshone them in reputation as greatly as he surpassed them in good works’. What king could resist that? In bringing to his subjects knowledge of the One God – Father, Son and Holy Spirit – the pope persuades Ethelbert that his ‘own merit and repute may excel that of all the former kings of [his] nation’.[17]

I am not suggesting that King Ethelbert wanted to model his entire realm on Rome. Rather, in adopting specifically the Roman model of a written system of laws, he was in his own mind laying a foundation for earthly immortality. Alongside his support for Augustine in establishing Christianity within his nation, his own written law was the proof, we might say, that he, like Emperor Constantine, ‘outshone’ his predecessors. The preservation of Ethelbert’s law code in Textus Roffensis is a unique witness to that.

Christianity is a religion of the book. This would have been vividly impressed upon Ethelbert when he looked upon the splendidly illuminated gospel book, known today as the St Augustine Gospels, which the missionaries probably brought with them from Rome (see image above).

This treasure has survived more than 1,400 years and is still used today at Canterbury Cathedral as part of the enthronement ceremony for archbishops. I imagine Ethelbert feeling the heft of the book, carefully turning its calf-skin pages, being captivated by the workings of the pen, enthralled by the gold and the spectrum of colours within its narrative scenes and evangelist portraits. Unfortunately for us, only one of the four portraits survive, that of Luke, but it is this very image that may well have held great import for this English king.

Impossible as it is to know exactly what Ethelbert felt, it is nevertheless a powerful image: Luke, the writer about this new god, Christ, sits on an elegant throne, surrounded by exquisite architectural framing, contemplative like a philosopher and, most intriguingly, holding a book. Written words are thus intrinsically intertwined with the regal and the wise. Authority is written. Words, it seems, live forever on the page.

We have no way of knowing exactly the path of inspiration that lead to Ethelbert’s creation of a written law code, but evidently the stimulus was at least in part external. Bede, after acknowledging that the king’s own wisdom conferred many benefits on the nation, highlights Ethelbert’s code of law as the outstanding example of this, and suggests too that the king was ‘inspired by the example of the Romans’.[16]

By this Bede may have meant Ethelbert was motivated to imitate Roman law, though in fact, there is little resemblance in the structure and content of Ethelbert’s code that would indicate this was the king’s direct concern. Rather, I would suggest that Bede simply meant that Ethelbert wanted to be like the Romans in having a written system of laws, and that this would elevate him and his kingdom beyond those rulers, past and present, who relied solely upon oral tradition. In having his law code written down, Ethelbert was staking his claim to Romanitas; in having it written in English, he was also asserting the validity of his own world.

For Ethelbert, the inspiration for the Roman way of doing things is most directly traceable to those men who had travelled to his kingdom from Rome, Augustine and the rest of the missionary delegation, whom of course he met face to face. However, the influence of the pope in Rome should not be underestimated.

Ethelbert’s motivations for writing his laws down can be at least intimated from the contents of the letter he received from Pope Gregory within a few years of his baptism. Appealing to Ethelbert as a glorious ruler over ‘the English nation’, Gregory urged the king to extend the Christian Faith among his people, following the example of Emperor Constantine who ‘in his day turned the Roman State from its ignorant worship of idols’ to submission to Christ.

The rewards for Ethelbert would ultimately, of course, be heavenly, but Gregory made it equally clear that his earthly majesty was also at stake. Constantine’s ‘glorious reputation has excelled that of all his predecessors’, the pope expounds, ‘and he has outshone them in reputation as greatly as he surpassed them in good works’. What king could resist that? In bringing to his subjects knowledge of the One God – Father, Son and Holy Spirit – the pope persuades Ethelbert that his ‘own merit and repute may excel that of all the former kings of [his] nation’.[17]

I am not suggesting that King Ethelbert wanted to model his entire realm on Rome. Rather, in adopting specifically the Roman model of a written system of laws, he was in his own mind laying a foundation for earthly immortality. Alongside his support for Augustine in establishing Christianity within his nation, his own written law was the proof, we might say, that he, like Emperor Constantine, ‘outshone’ his predecessors. The preservation of Ethelbert’s law code in Textus Roffensis is a unique witness to that.

The Laws of Ethelbert[18]

Translated from the Old English by Christopher Monk

1. God’s property and the Church’s, one should make good with a 12-fold compensation.

2. A bishop’s property, an 11-fold compensation.

3. A priest’s property, a 9-fold compensation.

4. A deacon’s property, a 6-fold compensation.

5. A cleric’s property, a 3-fold compensation.

6. Infringement of church peace, a 2-fold compensation.

7. Infringement of assembly peace, a 2-fold compensation.

8. If the king summons his people to him and someone does evil to them there, a 2-fold restitution and 50 shillings to the king. [The Kentish shilling was at this time a gold coin and may have equated to the value of one ox.][19]

9. If the king is drinking at a person’s home and someone does something false [or ‘corrupt’] there, that one should pay a two-fold restitution.

10. If a freeman steals from the king, he should make good 9-fold.

11. If a person slays someone in the house of the king, that one should pay 50 shillings.

12. If a person slays a freeman, 50 shillings to the king should be paid as ‘lord-money’ [OE drihtinbeag, literally ‘lord-ring’].

13. If a person slays an attendant, armourer or escort of the king, that one should pay an average ‘man-price’ [OE leodgeld; compare 24 below].

14. For violation of the king’s protection, 50 shillings. [Assault of anyone under the king’s protection.][20]

15. If a freeman steals from a freeman, he should make good 3-fold, and the king takes charge of [or ‘obtains’] the fine or all the goods.

16. If a person lies with the king’s maid, he should pay 50 shillings.

16.1. If she should be a grinding slave, he should pay 25 shillings.

16.2. If she should be third class, 12 shillings.

17. For the king’s feeding [OE fedesl], one should pay 20 shillings. [The fedesl was a contribution to the king’s sustenance as he moved about his realm. If a person defaulted on his responsibility to provide the king with sustenance, or wished to commute it to a monetary payment, he owed 20 shillings.][21]

18. If a person slays someone in a nobleman’s house, that one should pay 12 shillings. [The OE word for ‘nobleman’ is eorl (‘earl’), which in the context of this law probably refers to either a retainer to the king or a man awarded land by the king.][22]

19. If a person lies with a nobleman’s cupbearer, that one should pay 12 shillings.

20. For violation of a ceorl’s protection, 6 shillings. [A ceorl (‘churl’) was the lowest-ranked freeman.]

21. If a person lies with a ceorl’s cupbearer, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

21.1. For the second-rank servant, 50 sceattas. [At this time in Kent, twenty sceattas equalled one shilling. The sceatta was, like the shilling, a gold coin, equal to the weight of a grain of barley.][23]

21.2. For the third-rank, 30 sceattas.

22. If a person breaks into someone’s house first, that one should compensate with 6 shillings.

22.1. He who breaks in next, 3 shillings.

22.2. After that, each one a shilling.

23. If a person supplies weapons for someone where a quarrel occurs, and yet he does no evil, he [the supplier] should compensate with 6 shillings.

23.1. If highway robbery should be committed, he [the supplier] should compensate with 6 shillings.

23.2. If someone slays the person, he [the supplier] should compensate with 20 shillings.

24. If a person slays someone, he should pay an average ‘man-price’ of 100 shillings.

24.1. If a person slays someone, he should pay 20 shillings at the open grave and he should pay the whole of the ‘man-price’ within forty nights.

24.2. If the killer departs the land, the kinsmen should pay a half ‘man-price’.

25. If a person binds a freeman, he should pay 20 shillings.

26. If a person slays a ceorl’s domestic servant [OE hlaefæta], that one should compensate with 6 shillings. [A hlafæta, literally a ‘loaf-eater’, i.e. a dependent]

27. If a person slays a freed man [OE læt] of the highest rank, that one should pay with 80 shillings. [A læt was a freed slave, hence higher than a slave but lower than a ceorl; some læts may have originally been captured native Britons.][24]

27.1. If a person slays one of the second rank, one should pay with 60 shillings.

27.2. If of the third rank, one should pay with 40 shillings.

28. If a freeman breaks into an enclosure, he should recompense with 6 shillings.

28.1. If the person takes property from within, the person should make good with a three-fold compensation.

29. If a freeman enters an enclosure, let that one recompense with 4 shillings.

30. If a person slays someone, that one should pay with his own money or unblemished property, whichever.

31. If a freeman lies with a wife of another freeman, he should recompense with his wergild [‘man-price’] and obtain another wife with his own money and bring her to the other man at his home. [Grammatically, it is possible that ‘her wergild’ is meant.][25]

]32. If a person stabs through a rihthamscyld, one should make good with its value. [The word rihthamscyld, literally ‘right-home-shield’, is not attested elsewhere and its meaning is uncertain.][26]

33. If seizing of the hair [OE feaxfang] occurs, 50 sceattas as recompense. [As OE fang means ‘booty’, there is the possibility this refers to cutting the hair to show as a trophy of humiliation.]

34. If exposure of a bone occurs, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

35. If cutting of a bone occurs, one should compensate with 4 shillings.

36. If the outer skull [OE uterre hion] becomes broken, one should compensate with 10 shillings. [The meaning of hion is unclear as it is not used anywhere else in Old English texts; therefore ‘skull’ is a cautious translation. It may refer to the exposing of the skull.][27]

36.1. If both should be broken, one should compensate with 20 shillings. [This may refer to the skull being exposed and fractured.]

37. If a shoulder is made lame, one should compensate with 30 shillings.

38. If either ear is made deaf, one should compensate with 25 shillings.

39. If an ear is struck off, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

40. If an ear is pierced [or perhaps ‘perforated’], one should compensate with 3 shillings.

41. If an ear is gashed, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

42. If an eye is gouged out, one should compensate with 50 shillings.

43. If a mouth or eye is made crooked, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

44. If a nose is pierced, one should compensate with 9 shillings.

44.1. If it be on the cheek, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

44.2. If both [cheeks] are pierced, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

45. If a nose becomes gashed otherwise, one should compensate for any [gash] with 6 shillings.

46. If [the throat] becomes pierced, one should compensate with 6 shillings. [The scribe has missed out what it is that is being pierced; it has been suggested that throtu ‘throat’ was intended.][28]

47. He who breaks the jawbone, let him pay with 20 shillings.

48. For the four front teeth, 6 shillings each.

48.1. The tooth which stands to the side, 4 shillings.

48.2. The one which stands to the side of that one, 3 shillings.

48.3. Then each one after that, a shilling.

49. If speech becomes damaged, 12 shillings.

50. If a collarbone is broken, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

51. He who stabs through an arm, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

52. If an arm is broken, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

53. If one strikes off of thumb, 20 shillings.

54. If a thumbnail becomes detached, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

55. If a person strikes off a shooting finger [i.e. a forefinger], that one should compensate with 9 shillings.

56. If a person strikes off a middle finger, that one should compensate with 4 shillings.

57. If a person strikes off a gold-finger [i.e. a ring finger], that one should compensate with 6 shillings.

58. If a person strikes off the little finger, that one should compensate with 11 shillings.

59. For each of the fingernails, a shilling.

60. For the least facial disfigurement, 3 shillings.

60.1. And for the greater, 6 shillings.

61. If a person strikes another in the nose with a fist, 3 shillings.

61.1. If it be a blow, a shilling. [Perhaps this incorporates hitting with an object.]

61.2. If he receives a blow from a raised hand, one should pay a shilling.

61.3. If a blow becomes black [i.e. bruised] outside the clothing, one should compensate with 30 sceattas.

61.4. If it be inside the clothing, one should compensate each with 20 sceattas.

62. If the belly becomes wounded, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

62.1. If he is pierced through, one should compensate with 20 shillings.

63. If a person becomes healed, one should compensate with 30 shillings. [This is probably referring to the assailant paying medical fees.][29]

63.1. If a person be grievously wounded, one should compensate with 30 shillings. [This is probably referring to the wound preventing the person from working, and would be paid in addition to any medical fees.][30]

64. If a person destroys the genital ‘limb’, that person should pay him with three ‘man-prices’. [The high payment, i.e. the equivalent of the value of three men, suggests complete destruction of the genitals, and hence the injured man’s capacity to have children.]

64.1. If he stabs through it, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

64.2. If the person stabs into it, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

65. If a thigh becomes broken, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

65.1. If he becomes lame, then friends must arbitrate. [It is possible that the injury would require the use of a crutch and so it would have an impact on the use of an arm too, requiring further compensation, to be decided upon by the concerned parties.][31]

66. If a rib is broken, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

67. If a person stabs through a thigh, for each puncture 6 shillings.

67.1. If a wound is over an inch, a shilling.

67.2. For two inches, two shillings.

67.3. Over three, three shillings.

68. If a welt-wound occurs, one should pay 3 shillings.

69. If a foot is cut off, one should pay 50 shillings.

70. If the big toe is cut off, one should pay 10 shillings.

70.1. For the other toes, one should pay half the amount decided elsewhere for the fingers.

71. If the big toenail becomes removed, 30 sceattas as recompense.

71.1. For each of the others, one should pay 10 sceattas.

72. If a free-woman key-holder [OE friwif locbore] does anything corrupt, she should pay 30 shillings. [The woman here, literally ‘lock-bearer’, is most likely a house-keeper with responsibility for a household and its stores.][32]

73. Compensation for a maiden is as for a free man.

74. Assault/violation of the protection of the foremost widow of noble rank, one should pay 50 shillings.

74.1. Of the second rank, 20 shillings.

74.2. Of the third, 12 shillings.

74.3. Of the fourth, 6 shillings.

75. If a man takes/abducts a widow not belonging to him, the assault/violation of the protection should be recompensed with a 2-fold compensation.

76. If a man buys a maiden, the purchase stands if there is no deception.

76.1. If then there is deception, afterwards he shall bring [her] to [her] home, and one should repay him his money.

76.2. If she bears a living child, she should obtain half the property if the man [OE ceorl] dies first.

76.3. If she should wish to live with the children, she should obtain half the property.[33]

76.4. If she should wish to obtain another man [i.e. remarry], as for one child [i.e. she splits her inheritance with any children.][34]

76.5. If she does not bear a child, her father’s kin should obtain her property and the ‘morning-gift’ [i.e. the gift given to her by her husband on their marriage].

77. If a man abducts a maiden, to [her] owner he should pay 50 shillings, and afterwards he must procure from the owner his consent [i.e. to marry her].

77.1. If she should be betrothed through goods to another man, he should pay 20 shillings.

77.2. If a return [of the maiden] happens, 35 shillings and 15 shillings to the king.

78. If a person lies with a servant’s wife while the husband is alive, he should pay back 2-fold.

79. If a servant should slay another who is innocent, one should pay back the entire worth. [This may refer to the owner of the guilty servant compensating the owner of the innocent one.][35]

80. If a servant’s eye, or foot, is removed, one should pay to him [i.e. the master] the entire worth.

81. If a person binds another’s servant, that one should compensate with 6 shillings.

82. A slave’s highway robbery shall be paid for with 3 shillings.

83. If a slave steals he should recompense with a 2-fold compensation.

Translated from the Old English by Christopher Monk

1. God’s property and the Church’s, one should make good with a 12-fold compensation.

2. A bishop’s property, an 11-fold compensation.

3. A priest’s property, a 9-fold compensation.

4. A deacon’s property, a 6-fold compensation.

5. A cleric’s property, a 3-fold compensation.

6. Infringement of church peace, a 2-fold compensation.

7. Infringement of assembly peace, a 2-fold compensation.

8. If the king summons his people to him and someone does evil to them there, a 2-fold restitution and 50 shillings to the king. [The Kentish shilling was at this time a gold coin and may have equated to the value of one ox.][19]

9. If the king is drinking at a person’s home and someone does something false [or ‘corrupt’] there, that one should pay a two-fold restitution.

10. If a freeman steals from the king, he should make good 9-fold.

11. If a person slays someone in the house of the king, that one should pay 50 shillings.

12. If a person slays a freeman, 50 shillings to the king should be paid as ‘lord-money’ [OE drihtinbeag, literally ‘lord-ring’].

13. If a person slays an attendant, armourer or escort of the king, that one should pay an average ‘man-price’ [OE leodgeld; compare 24 below].

14. For violation of the king’s protection, 50 shillings. [Assault of anyone under the king’s protection.][20]

15. If a freeman steals from a freeman, he should make good 3-fold, and the king takes charge of [or ‘obtains’] the fine or all the goods.

16. If a person lies with the king’s maid, he should pay 50 shillings.

16.1. If she should be a grinding slave, he should pay 25 shillings.

16.2. If she should be third class, 12 shillings.

17. For the king’s feeding [OE fedesl], one should pay 20 shillings. [The fedesl was a contribution to the king’s sustenance as he moved about his realm. If a person defaulted on his responsibility to provide the king with sustenance, or wished to commute it to a monetary payment, he owed 20 shillings.][21]

18. If a person slays someone in a nobleman’s house, that one should pay 12 shillings. [The OE word for ‘nobleman’ is eorl (‘earl’), which in the context of this law probably refers to either a retainer to the king or a man awarded land by the king.][22]

19. If a person lies with a nobleman’s cupbearer, that one should pay 12 shillings.

20. For violation of a ceorl’s protection, 6 shillings. [A ceorl (‘churl’) was the lowest-ranked freeman.]

21. If a person lies with a ceorl’s cupbearer, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

21.1. For the second-rank servant, 50 sceattas. [At this time in Kent, twenty sceattas equalled one shilling. The sceatta was, like the shilling, a gold coin, equal to the weight of a grain of barley.][23]

21.2. For the third-rank, 30 sceattas.

22. If a person breaks into someone’s house first, that one should compensate with 6 shillings.

22.1. He who breaks in next, 3 shillings.

22.2. After that, each one a shilling.

23. If a person supplies weapons for someone where a quarrel occurs, and yet he does no evil, he [the supplier] should compensate with 6 shillings.

23.1. If highway robbery should be committed, he [the supplier] should compensate with 6 shillings.

23.2. If someone slays the person, he [the supplier] should compensate with 20 shillings.

24. If a person slays someone, he should pay an average ‘man-price’ of 100 shillings.

24.1. If a person slays someone, he should pay 20 shillings at the open grave and he should pay the whole of the ‘man-price’ within forty nights.

24.2. If the killer departs the land, the kinsmen should pay a half ‘man-price’.

25. If a person binds a freeman, he should pay 20 shillings.

26. If a person slays a ceorl’s domestic servant [OE hlaefæta], that one should compensate with 6 shillings. [A hlafæta, literally a ‘loaf-eater’, i.e. a dependent]

27. If a person slays a freed man [OE læt] of the highest rank, that one should pay with 80 shillings. [A læt was a freed slave, hence higher than a slave but lower than a ceorl; some læts may have originally been captured native Britons.][24]

27.1. If a person slays one of the second rank, one should pay with 60 shillings.

27.2. If of the third rank, one should pay with 40 shillings.

28. If a freeman breaks into an enclosure, he should recompense with 6 shillings.

28.1. If the person takes property from within, the person should make good with a three-fold compensation.

29. If a freeman enters an enclosure, let that one recompense with 4 shillings.

30. If a person slays someone, that one should pay with his own money or unblemished property, whichever.

31. If a freeman lies with a wife of another freeman, he should recompense with his wergild [‘man-price’] and obtain another wife with his own money and bring her to the other man at his home. [Grammatically, it is possible that ‘her wergild’ is meant.][25]

]32. If a person stabs through a rihthamscyld, one should make good with its value. [The word rihthamscyld, literally ‘right-home-shield’, is not attested elsewhere and its meaning is uncertain.][26]

33. If seizing of the hair [OE feaxfang] occurs, 50 sceattas as recompense. [As OE fang means ‘booty’, there is the possibility this refers to cutting the hair to show as a trophy of humiliation.]

34. If exposure of a bone occurs, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

35. If cutting of a bone occurs, one should compensate with 4 shillings.

36. If the outer skull [OE uterre hion] becomes broken, one should compensate with 10 shillings. [The meaning of hion is unclear as it is not used anywhere else in Old English texts; therefore ‘skull’ is a cautious translation. It may refer to the exposing of the skull.][27]

36.1. If both should be broken, one should compensate with 20 shillings. [This may refer to the skull being exposed and fractured.]

37. If a shoulder is made lame, one should compensate with 30 shillings.

38. If either ear is made deaf, one should compensate with 25 shillings.

39. If an ear is struck off, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

40. If an ear is pierced [or perhaps ‘perforated’], one should compensate with 3 shillings.

41. If an ear is gashed, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

42. If an eye is gouged out, one should compensate with 50 shillings.

43. If a mouth or eye is made crooked, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

44. If a nose is pierced, one should compensate with 9 shillings.

44.1. If it be on the cheek, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

44.2. If both [cheeks] are pierced, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

45. If a nose becomes gashed otherwise, one should compensate for any [gash] with 6 shillings.

46. If [the throat] becomes pierced, one should compensate with 6 shillings. [The scribe has missed out what it is that is being pierced; it has been suggested that throtu ‘throat’ was intended.][28]

47. He who breaks the jawbone, let him pay with 20 shillings.

48. For the four front teeth, 6 shillings each.

48.1. The tooth which stands to the side, 4 shillings.

48.2. The one which stands to the side of that one, 3 shillings.

48.3. Then each one after that, a shilling.

49. If speech becomes damaged, 12 shillings.

50. If a collarbone is broken, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

51. He who stabs through an arm, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

52. If an arm is broken, one should compensate with 6 shillings.

53. If one strikes off of thumb, 20 shillings.

54. If a thumbnail becomes detached, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

55. If a person strikes off a shooting finger [i.e. a forefinger], that one should compensate with 9 shillings.

56. If a person strikes off a middle finger, that one should compensate with 4 shillings.

57. If a person strikes off a gold-finger [i.e. a ring finger], that one should compensate with 6 shillings.

58. If a person strikes off the little finger, that one should compensate with 11 shillings.

59. For each of the fingernails, a shilling.

60. For the least facial disfigurement, 3 shillings.

60.1. And for the greater, 6 shillings.

61. If a person strikes another in the nose with a fist, 3 shillings.

61.1. If it be a blow, a shilling. [Perhaps this incorporates hitting with an object.]

61.2. If he receives a blow from a raised hand, one should pay a shilling.

61.3. If a blow becomes black [i.e. bruised] outside the clothing, one should compensate with 30 sceattas.

61.4. If it be inside the clothing, one should compensate each with 20 sceattas.

62. If the belly becomes wounded, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

62.1. If he is pierced through, one should compensate with 20 shillings.

63. If a person becomes healed, one should compensate with 30 shillings. [This is probably referring to the assailant paying medical fees.][29]

63.1. If a person be grievously wounded, one should compensate with 30 shillings. [This is probably referring to the wound preventing the person from working, and would be paid in addition to any medical fees.][30]

64. If a person destroys the genital ‘limb’, that person should pay him with three ‘man-prices’. [The high payment, i.e. the equivalent of the value of three men, suggests complete destruction of the genitals, and hence the injured man’s capacity to have children.]

64.1. If he stabs through it, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

64.2. If the person stabs into it, he should compensate with 6 shillings.

65. If a thigh becomes broken, one should compensate with 12 shillings.

65.1. If he becomes lame, then friends must arbitrate. [It is possible that the injury would require the use of a crutch and so it would have an impact on the use of an arm too, requiring further compensation, to be decided upon by the concerned parties.][31]

66. If a rib is broken, one should compensate with 3 shillings.

67. If a person stabs through a thigh, for each puncture 6 shillings.

67.1. If a wound is over an inch, a shilling.

67.2. For two inches, two shillings.

67.3. Over three, three shillings.

68. If a welt-wound occurs, one should pay 3 shillings.

69. If a foot is cut off, one should pay 50 shillings.

70. If the big toe is cut off, one should pay 10 shillings.

70.1. For the other toes, one should pay half the amount decided elsewhere for the fingers.

71. If the big toenail becomes removed, 30 sceattas as recompense.

71.1. For each of the others, one should pay 10 sceattas.

72. If a free-woman key-holder [OE friwif locbore] does anything corrupt, she should pay 30 shillings. [The woman here, literally ‘lock-bearer’, is most likely a house-keeper with responsibility for a household and its stores.][32]

73. Compensation for a maiden is as for a free man.

74. Assault/violation of the protection of the foremost widow of noble rank, one should pay 50 shillings.

74.1. Of the second rank, 20 shillings.

74.2. Of the third, 12 shillings.

74.3. Of the fourth, 6 shillings.

75. If a man takes/abducts a widow not belonging to him, the assault/violation of the protection should be recompensed with a 2-fold compensation.

76. If a man buys a maiden, the purchase stands if there is no deception.

76.1. If then there is deception, afterwards he shall bring [her] to [her] home, and one should repay him his money.

76.2. If she bears a living child, she should obtain half the property if the man [OE ceorl] dies first.

76.3. If she should wish to live with the children, she should obtain half the property.[33]

76.4. If she should wish to obtain another man [i.e. remarry], as for one child [i.e. she splits her inheritance with any children.][34]

76.5. If she does not bear a child, her father’s kin should obtain her property and the ‘morning-gift’ [i.e. the gift given to her by her husband on their marriage].

77. If a man abducts a maiden, to [her] owner he should pay 50 shillings, and afterwards he must procure from the owner his consent [i.e. to marry her].

77.1. If she should be betrothed through goods to another man, he should pay 20 shillings.

77.2. If a return [of the maiden] happens, 35 shillings and 15 shillings to the king.

78. If a person lies with a servant’s wife while the husband is alive, he should pay back 2-fold.

79. If a servant should slay another who is innocent, one should pay back the entire worth. [This may refer to the owner of the guilty servant compensating the owner of the innocent one.][35]

80. If a servant’s eye, or foot, is removed, one should pay to him [i.e. the master] the entire worth.

81. If a person binds another’s servant, that one should compensate with 6 shillings.

82. A slave’s highway robbery shall be paid for with 3 shillings.

83. If a slave steals he should recompense with a 2-fold compensation.

Notes

[1] I use Ethelbert throughout. The more scholarly form of the name is Æthelberht.

[2] Ben Snook, ‘Who Introduced Charters into England? The Case for Theodore and Hadrian’, in Textus Roffensis: Law, Language, and Libraries in Early Medieval England, ed. Bruce O’ Brien and Barbara Bombi (Turnhout: Brepols, 2015), pp. 257–289.

[3] Quotations from Bede’s work are from the accessible Penguin Classics translation by Leo Shirley Price: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (London: Penguin, revised edition 1990), herein HE. Bede’s accounts relating to Ethelbert are found in book 1, chapters 25, 26, 32 and 33, and in book 2, chapters 3 and 5.

[4] Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 154. For a very thorough discussion of Ethelbert’s political motives for converting to the Christian faith, an excellent resource is chapter 2 in Higham’s The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997).

[5] HE, p. 111.

[6] HE, p. 111.

[7] HE, p. 75.

[8] HE, p. 75.

[9] HE, p. 76.

[10] HE, p. 75.

[11] HE, pp. 75, 76.

[12] HE, p. 76.

[13] HE, p. 77.

[14] HE, p. 77.

[15] HE, p. 77.

[16] HE, p. 111.

[17] HE, pp. 94, 95.

[18] There is no numbering system in the manuscript; I have followed Lisi Oliver's numbering in her The Beginnings of English Law (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 2002), pp. 60–81.

[19] Hector Munro Chadwick, Studies on Anglo-Saxon Institutions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1905; reprint New York, 1963), p. 61.

[20] See E.G. Stanley, ‘Some words for the dictionary of Old English’, Subsidia 26 (1998), 39-47, mund.

[21] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 86, 87.

[22] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 89.

[23] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 82.

[24] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 91–93.

[25] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 90.

[26] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 97, 98.

[27] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 101, 102.

[28] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 70

[29] Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 104, 105.

[30] Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 104, 105.

[31] Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 99, 100.

[32] Christine Fell, ‘A “friwif locbore” revisited’, Anglo-Saxon England 13 (1984), 157–66; Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 110,111.

[33] For a discussion of this and the following clause, see Carole Hough, ‘The early Kentish “divorce laws”: a reconsideration of Æthelberht, chs. 79 and 80’, Anglo-Saxon England 23 (1994), 19–34.

[34] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 79.

[35] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 115.

[1] I use Ethelbert throughout. The more scholarly form of the name is Æthelberht.

[2] Ben Snook, ‘Who Introduced Charters into England? The Case for Theodore and Hadrian’, in Textus Roffensis: Law, Language, and Libraries in Early Medieval England, ed. Bruce O’ Brien and Barbara Bombi (Turnhout: Brepols, 2015), pp. 257–289.

[3] Quotations from Bede’s work are from the accessible Penguin Classics translation by Leo Shirley Price: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (London: Penguin, revised edition 1990), herein HE. Bede’s accounts relating to Ethelbert are found in book 1, chapters 25, 26, 32 and 33, and in book 2, chapters 3 and 5.

[4] Nicholas J. Higham and Martin J. Ryan, The Anglo-Saxon World (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), p. 154. For a very thorough discussion of Ethelbert’s political motives for converting to the Christian faith, an excellent resource is chapter 2 in Higham’s The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997).

[5] HE, p. 111.

[6] HE, p. 111.

[7] HE, p. 75.

[8] HE, p. 75.

[9] HE, p. 76.

[10] HE, p. 75.

[11] HE, pp. 75, 76.

[12] HE, p. 76.

[13] HE, p. 77.

[14] HE, p. 77.

[15] HE, p. 77.

[16] HE, p. 111.

[17] HE, pp. 94, 95.

[18] There is no numbering system in the manuscript; I have followed Lisi Oliver's numbering in her The Beginnings of English Law (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 2002), pp. 60–81.

[19] Hector Munro Chadwick, Studies on Anglo-Saxon Institutions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1905; reprint New York, 1963), p. 61.

[20] See E.G. Stanley, ‘Some words for the dictionary of Old English’, Subsidia 26 (1998), 39-47, mund.

[21] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 86, 87.

[22] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 89.

[23] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 82.

[24] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 91–93.

[25] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 90.

[26] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 97, 98.

[27] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, pp. 101, 102.

[28] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 70

[29] Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 104, 105.

[30] Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 104, 105.

[31] Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 99, 100.

[32] Christine Fell, ‘A “friwif locbore” revisited’, Anglo-Saxon England 13 (1984), 157–66; Oliver, Beginnings of English Laws, pp. 110,111.

[33] For a discussion of this and the following clause, see Carole Hough, ‘The early Kentish “divorce laws”: a reconsideration of Æthelberht, chs. 79 and 80’, Anglo-Saxon England 23 (1994), 19–34.

[34] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 79.

[35] Oliver, Beginnings of English Law, p. 115.