Custumale Roffense

An overview of the thirteenth-century custumal of Rochester Cathedral priory

By Christopher Monk © 2016/2018

A custumal (in Latin custumale) is a medieval survey of the payments, services and obligations (collectively known as 'customs') owed by tenants of a manor to the lord of the manor. The Rochester custumal (Custumale Roffense) dates to the thirteenth century and is a record of what was due the Benedictine monastery of St Andrew's Priory, which lay adjacent to Rochester Cathedral. It records payments (both monetary and food rents), agricultural services (such as ploughing and harvesting), and other regulations affecting the lives of all those who held and farmed land in the manors, or estates, owned by the monastery. It is written in Latin.

In addition to providing a detailed overview of the monastery's revenue from various sources (not only the tenant payments mentioned above, but also such things as altar rents and tithings), this custumal also records certain outgoings and expenses (for example, almsgiving and the maintenance of St Bartholomew's Hospital); and it provides an insight into the economic organisation of the obedientaries (the various monks in their official capacities), such as the chamberlain and cellarer, all of whom would have kept discrete accounts records.

A rather fascinating feature of this book is its detailed account of the duties and wages of the lay servants who worked within the monastery precinct. And there are other miscellaneous items of historical importance, such as a record of the ‘Romescot’ tax due from southern cathedrals in England, the Assize of Bread passed by Richard the Lionheart, and the maintenance of Rochester Bridge. Even medicine finds its way into the custumal, with the slightly later additions of two medical recipes, one for male bladder problems and the other for ulcerated skin.

By Christopher Monk © 2016/2018

A custumal (in Latin custumale) is a medieval survey of the payments, services and obligations (collectively known as 'customs') owed by tenants of a manor to the lord of the manor. The Rochester custumal (Custumale Roffense) dates to the thirteenth century and is a record of what was due the Benedictine monastery of St Andrew's Priory, which lay adjacent to Rochester Cathedral. It records payments (both monetary and food rents), agricultural services (such as ploughing and harvesting), and other regulations affecting the lives of all those who held and farmed land in the manors, or estates, owned by the monastery. It is written in Latin.

In addition to providing a detailed overview of the monastery's revenue from various sources (not only the tenant payments mentioned above, but also such things as altar rents and tithings), this custumal also records certain outgoings and expenses (for example, almsgiving and the maintenance of St Bartholomew's Hospital); and it provides an insight into the economic organisation of the obedientaries (the various monks in their official capacities), such as the chamberlain and cellarer, all of whom would have kept discrete accounts records.

A rather fascinating feature of this book is its detailed account of the duties and wages of the lay servants who worked within the monastery precinct. And there are other miscellaneous items of historical importance, such as a record of the ‘Romescot’ tax due from southern cathedrals in England, the Assize of Bread passed by Richard the Lionheart, and the maintenance of Rochester Bridge. Even medicine finds its way into the custumal, with the slightly later additions of two medical recipes, one for male bladder problems and the other for ulcerated skin.

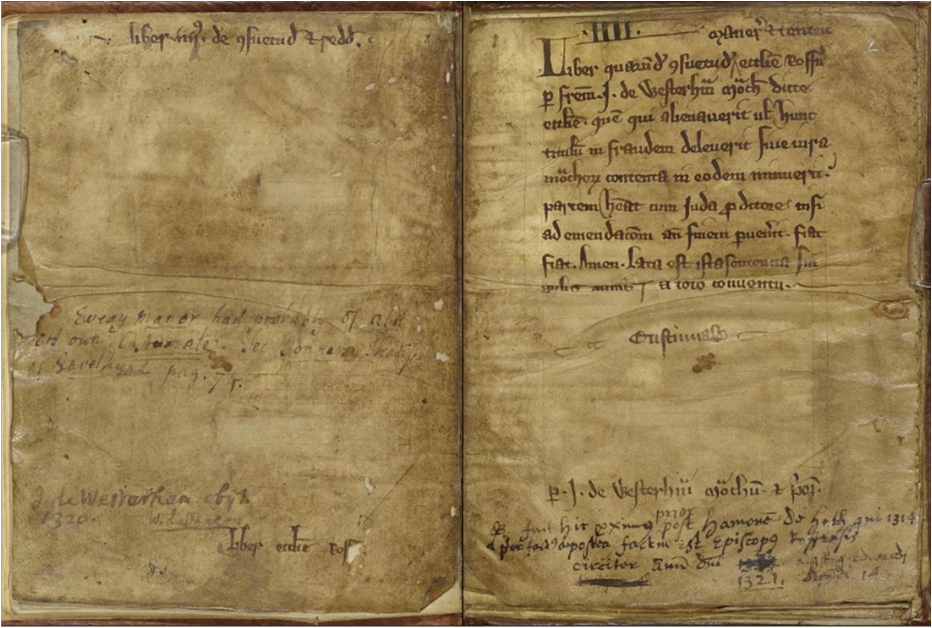

The title page (right hand side) of Custumale Roffense. Maidstone, CKS, DRc/R2 (Rochester, c.1275 - c.1325), folios 1v-2r.

All images of Custumale Roffense by permission of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral.

All images of Custumale Roffense by permission of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral.

Dating the manuscript

The title page, folio 2r, was written some time after the main scribes wrote the majority of the text in the book. It is written in a late thirteenth-century/early fourteenth-century ecclesiastical document hand and names Brother J. de Westerham as the compiler. Westerham is described as a monk of the church of Rochester (i.e. a monk at the priory of St Andrew’s cathedral church). He apparently was a monk there for some time during the latter part of the thirteenth century before eventually working his way up to the most senior position of prior (1320-1321), but he died soon thereafter.

The title page, folio 2r, was written some time after the main scribes wrote the majority of the text in the book. It is written in a late thirteenth-century/early fourteenth-century ecclesiastical document hand and names Brother J. de Westerham as the compiler. Westerham is described as a monk of the church of Rochester (i.e. a monk at the priory of St Andrew’s cathedral church). He apparently was a monk there for some time during the latter part of the thirteenth century before eventually working his way up to the most senior position of prior (1320-1321), but he died soon thereafter.

Copies of entries from the Domesday Book. Custumale Roffense, folios 7v and 8r.

The scribe of the title page also probably wrote the text on folio 7v-8r, entries documenting information from the Domesday Book. Of particular note is the entry on 8r, which establishes the ownership of the estate of Haddenham in Buckinghamshire, granted to the monastery after the Norman Conquest (1066). Since many of the subsequent entries relate to this estate, which is outside of Rochester’s diocese, this scribe obviously thought it prudent to have the monastic rights to the estate firmly established. The same scribe most likely also wrote the entry concerning Rent of Haddenham pertaining to the Sacristy which appears later on folios 28v-29r.

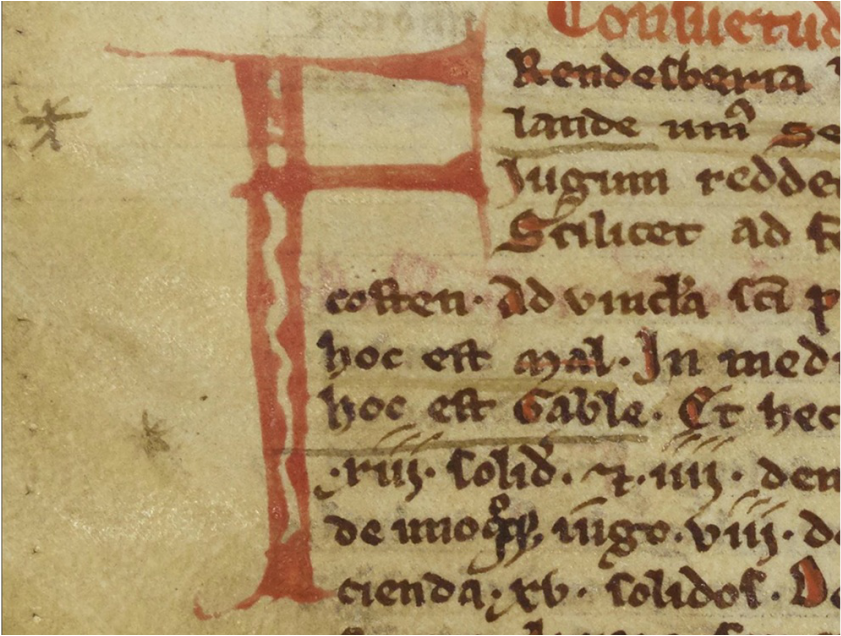

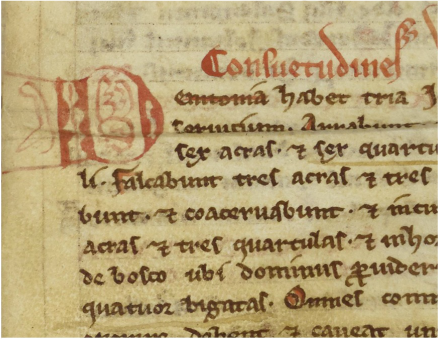

The ‘custumal proper’, the text which forms part of what was most likely the originally planned book, begins at folio 9 and continues to the end of the book at folio 68. The majority of the first part of this, up to 52v, is written in a thirteenth-century Gothic textura script, as are folios 3-5, and represent the work of a single scribe. The remainder is also thirteenth-century, though in a variant form of gothic script – it is a rounder hand and in a lighter coloured ink – and so probably represents a different, though likely contemporary, scribe’s work.

The only other hand, possibly hands, at work (other than those of doodlers and annotators) can be seen on folio 2v. There two entries have been written in a somewhat untidy fourteenth-century script.

The above suggests we should date the compiling and writing of Custumale Roffense to about c.1275-c.1325, with the ‘custumal proper’ being written in the first half of that date range; thus we can say that Custumale Roffense was produced in the late thirteenth century, with additions being made in the early part of the fourteenth century.

The ‘custumal proper’, the text which forms part of what was most likely the originally planned book, begins at folio 9 and continues to the end of the book at folio 68. The majority of the first part of this, up to 52v, is written in a thirteenth-century Gothic textura script, as are folios 3-5, and represent the work of a single scribe. The remainder is also thirteenth-century, though in a variant form of gothic script – it is a rounder hand and in a lighter coloured ink – and so probably represents a different, though likely contemporary, scribe’s work.

The only other hand, possibly hands, at work (other than those of doodlers and annotators) can be seen on folio 2v. There two entries have been written in a somewhat untidy fourteenth-century script.

The above suggests we should date the compiling and writing of Custumale Roffense to about c.1275-c.1325, with the ‘custumal proper’ being written in the first half of that date range; thus we can say that Custumale Roffense was produced in the late thirteenth century, with additions being made in the early part of the fourteenth century.

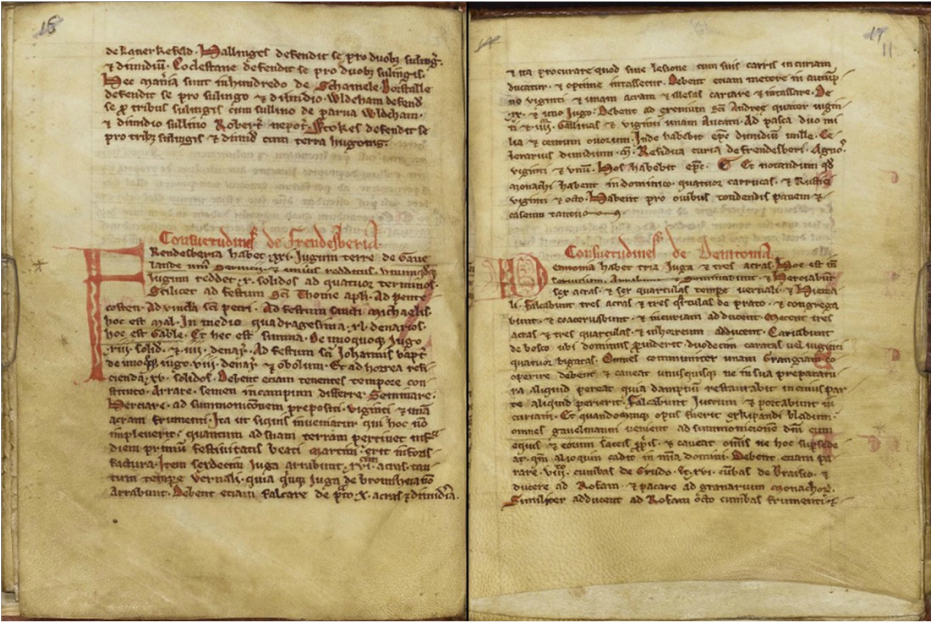

Customs owed from Frindsbury and Denton, with details below of the decorated initials. Custumale Roffense, folios 10v and 11r.

Contents

By far the majority of the custumal does what it’s supposed to do, recording the customs (rents, services and obligations) of those families who lived on and worked the monastery's manorial estates. By the thirteenth century, rents were evidently paid not only to the community of monks as a whole but directly to key officers, or obedientaries, within the monastic order. Those mentioned include the prior, the chamberlain, the cellarer, the sacristan, the almoner, and the choir official. These evidently maintained their own accounts records as they related to the community. In the case of the prior, the head of the monastery, he was expected to maintain his own lodging and table for sharing hospitality with visitors, and this too had to be carefully accounted for.

By far the majority of the custumal does what it’s supposed to do, recording the customs (rents, services and obligations) of those families who lived on and worked the monastery's manorial estates. By the thirteenth century, rents were evidently paid not only to the community of monks as a whole but directly to key officers, or obedientaries, within the monastic order. Those mentioned include the prior, the chamberlain, the cellarer, the sacristan, the almoner, and the choir official. These evidently maintained their own accounts records as they related to the community. In the case of the prior, the head of the monastery, he was expected to maintain his own lodging and table for sharing hospitality with visitors, and this too had to be carefully accounted for.

Customs due the Bishop of Rochester from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Custumale Roffense, folio 67v.

An item of particular interest is that found toward the end of the book which lists the customs owed by ‘the master of Canterbury’, that is, the archbishop. The history between Canterbury (the oldest bishopric in England) and Rochester (the second oldest) is fascinating. William the Conqueror (reigned 1066-1087) appointed his half-brother Bishop Odo of Bayeux as Earl of Kent. As such, he began to encroach upon lands owned by Rochester Cathedral, which obviously had an impact on the livelihood of the monastery. This was remedied at the famous trial of Penenden Heath (c.1072), enabling Archbishop Lanfranc to return lands to both Rochester and Canterbury.

What is interesting about the entry is that the heading emphasises that the customs were to be paid 'evidently to the Bishop of Rochester’. It would seem that such an emphasis was needed so that the prior didn’t attempt to gain the bishop's funds for the monks themselves.

What is interesting about the entry is that the heading emphasises that the customs were to be paid 'evidently to the Bishop of Rochester’. It would seem that such an emphasis was needed so that the prior didn’t attempt to gain the bishop's funds for the monks themselves.

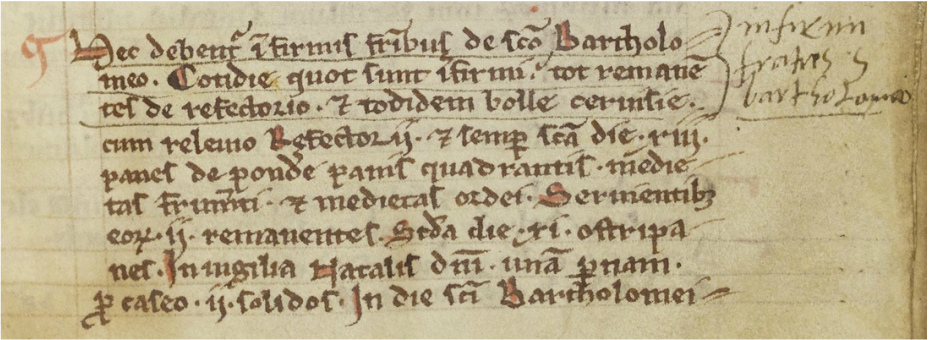

'Here is what is owed to the sick brothers of Saint Bartholomew'. Custumale Roffense, folio 47r.

Particularly noteworthy entries relating to financial outgoings include major support of St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Rochester, which until its recent closure, in 2016, was the oldest surviving hospital in England; alms-giving to the poor on the anniversaries of the deaths of Rochester bishops Gundulf and Ernulf; and maintenance of Rochester Bridge.

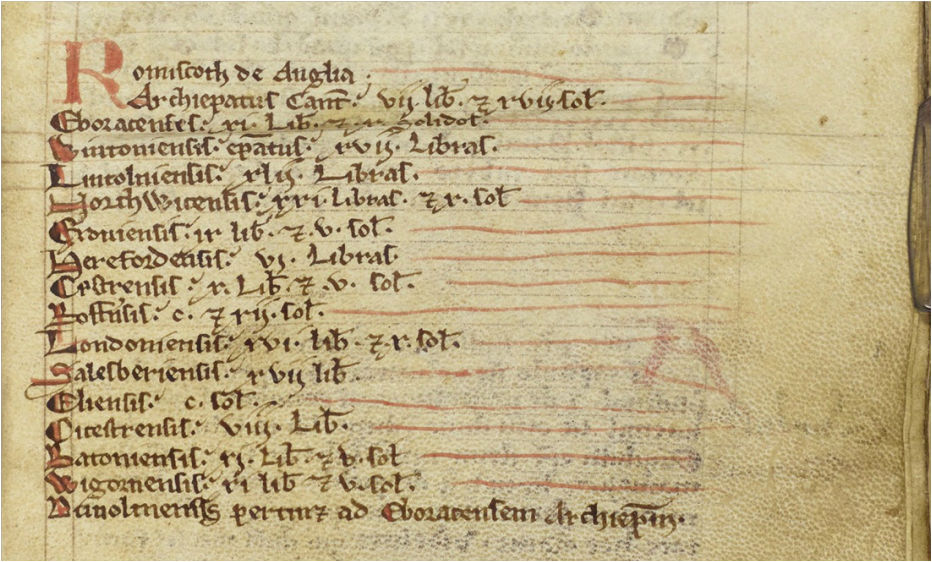

The custumal also includes a record of the payments of Romescot, or Peter’s Pence, in England. This was a 'penny per hearth' tax on households, sent to the papal see in Rome, and organised according to the jurisdictions of archbishops and bishops. The bishopric, or diocese, of Rochester was evidently one of the smallest of these districts, owing just 112 shillings (£5 and 12 shillings) per year, whereas Lincoln owed £42, nearly twice as much as the second largest district, Norwich.

The custumal also includes a record of the payments of Romescot, or Peter’s Pence, in England. This was a 'penny per hearth' tax on households, sent to the papal see in Rome, and organised according to the jurisdictions of archbishops and bishops. The bishopric, or diocese, of Rochester was evidently one of the smallest of these districts, owing just 112 shillings (£5 and 12 shillings) per year, whereas Lincoln owed £42, nearly twice as much as the second largest district, Norwich.

'Romescot of England'. Custumale Roffense, folio 27r.

Agriculture and economics

Many of the entries record non-financial dues, that is, food rents. These were paid by the monastery’s farm estates and were obviously essential to the livelihood of the community. Foods listed in one entry (39v-40r) include: wheat, peas, barley for servants and the poor, barley groats (coarse meal), oats, cheese (specifically for the archbishop), honey, and bacon. In addition, the estates owed dues for tallow (for candles), salt and firewood.

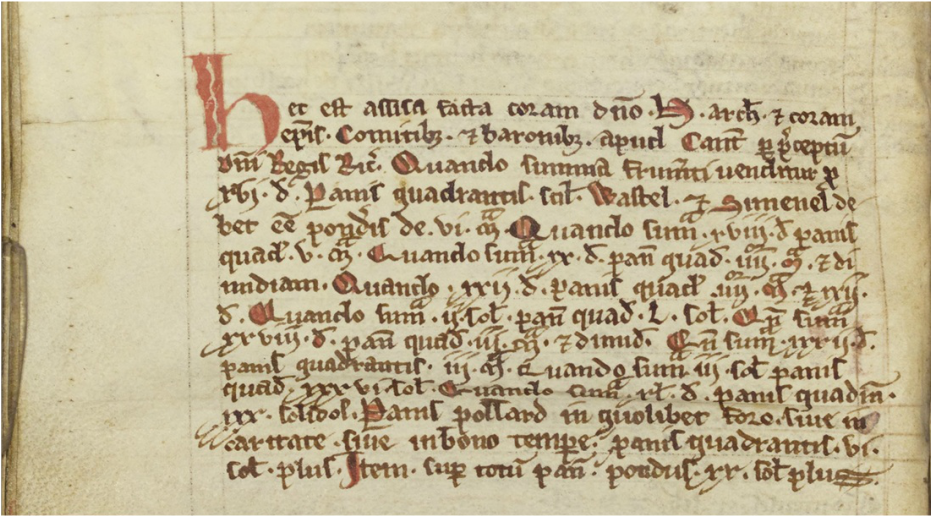

The fascinating Assize of Bread (27v) is a statute originally recorded at Canterbury towards the end of the twelfth century, under the view of the Bishop of Rochester and by order of Richard I (the Lionheart, reigned 1189-1199), and which evidently remained in force for some time. This, and similar assizes throughout the thirteenth century (some also concerning ale/beer), regulated the price, weight and quality of bread manufactured and sold in towns and villages.

Many of the entries record non-financial dues, that is, food rents. These were paid by the monastery’s farm estates and were obviously essential to the livelihood of the community. Foods listed in one entry (39v-40r) include: wheat, peas, barley for servants and the poor, barley groats (coarse meal), oats, cheese (specifically for the archbishop), honey, and bacon. In addition, the estates owed dues for tallow (for candles), salt and firewood.

The fascinating Assize of Bread (27v) is a statute originally recorded at Canterbury towards the end of the twelfth century, under the view of the Bishop of Rochester and by order of Richard I (the Lionheart, reigned 1189-1199), and which evidently remained in force for some time. This, and similar assizes throughout the thirteenth century (some also concerning ale/beer), regulated the price, weight and quality of bread manufactured and sold in towns and villages.

'Here is the assize made in the presence of the Lord Archbishop H[ubert Walter], and in the presence of the Bishop, earls and barons, at Canterbury by the order of the Lord King Richard.' Custumale Roffense, folio 27v.

Lay servants

When we compare thirteenth-century English monastic culture to that in Anglo-Saxon England (roughly the seventh to the eleventh centuries), it’s clear that a big shift had taken place: from the earlier self-reliant ethos of the Anglo-Saxon communities, where the monks carried out much (though not all) of the labour themselves, to the firmly established positions of waged lay servants in the monastic communities of the later medieval period.

Custumal Roffense is important historically for what it reveals about the organisation of the servants at St Andrew’s. The description of this takes up folios 53r-60v and shows the key service positions: the millers (who also served as bakers), who were divided into chief miller, secondary miller and three other millers; the brewers; the cooks; the steward; the gatekeeper; the granger; the porter of the cellar; the infirmary attendant; church attendants; tailors (who were also the tanners); and, last but not least, the launderers. Wages varied for these positions – higher wages were reserved for the senior positions of steward, gatekeeper, chief miller and head cook – and were paid at Christmas and Easter.

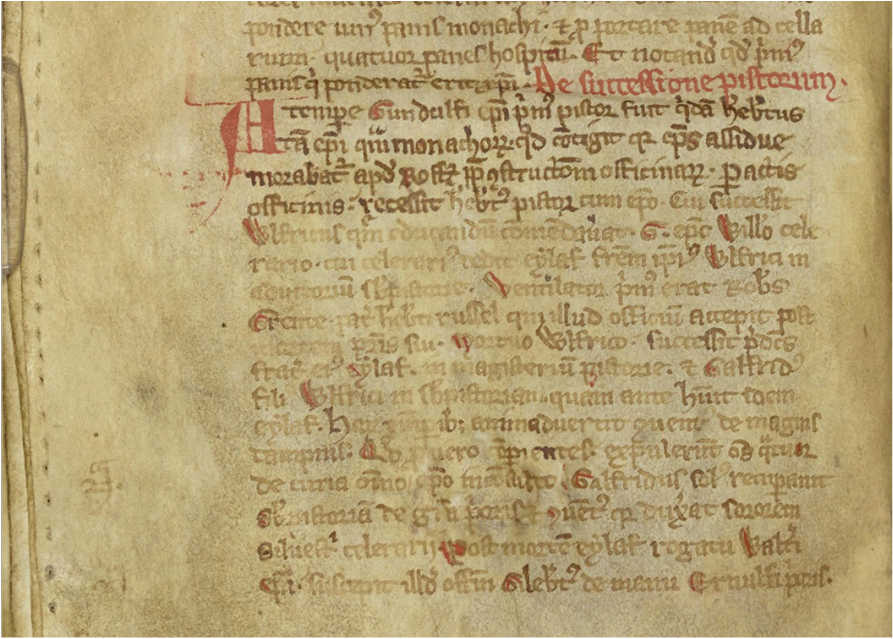

One particularly remarkable feature of this section is the story of the succession of the millers, which reveals a 'trouble at mill' tale of corruption and nepotism. Custumale Roffense is certainly not just a dry account of financial revenues.

When we compare thirteenth-century English monastic culture to that in Anglo-Saxon England (roughly the seventh to the eleventh centuries), it’s clear that a big shift had taken place: from the earlier self-reliant ethos of the Anglo-Saxon communities, where the monks carried out much (though not all) of the labour themselves, to the firmly established positions of waged lay servants in the monastic communities of the later medieval period.

Custumal Roffense is important historically for what it reveals about the organisation of the servants at St Andrew’s. The description of this takes up folios 53r-60v and shows the key service positions: the millers (who also served as bakers), who were divided into chief miller, secondary miller and three other millers; the brewers; the cooks; the steward; the gatekeeper; the granger; the porter of the cellar; the infirmary attendant; church attendants; tailors (who were also the tanners); and, last but not least, the launderers. Wages varied for these positions – higher wages were reserved for the senior positions of steward, gatekeeper, chief miller and head cook – and were paid at Christmas and Easter.

One particularly remarkable feature of this section is the story of the succession of the millers, which reveals a 'trouble at mill' tale of corruption and nepotism. Custumale Roffense is certainly not just a dry account of financial revenues.

Trouble at mill: the story of the succession of the millers reveals a tale of corruption and nepotism. Custumale Roffense, folio 53v.

It seems appropriate to conclude this overview of Custumale Roffense by referring to the reviewer of the printed edition of this medieval text published by John Thorpe in 1788. Writing in The Monthly Review of that year, the reviewer is dismissive of the manuscript's appeal: ‘Extracts from it would not be interesting to the generality of our readers.’ (The Monthly Review, volume 79, July-December 1788.) I think we should politely disagree.

Selected bibliography

British History Online, ‘Parishes: Haddenham’ (http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol2/pp281-286#fnn5, accessed 30/06/2016).

E. J. Greenwood, The Hospital of St Bartholomew Rochester (1962).

R. H. Snape, English Monastic Finances in the Later Middle Ages (1926).

Johannes de Westerham, Custumale Roffense, from the original manuscript in the archives of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester, etc, edited by John Thorpe (1788).

If you would like any further information on Custumale Roffense please feel free to contact me.

Selected bibliography

British History Online, ‘Parishes: Haddenham’ (http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/bucks/vol2/pp281-286#fnn5, accessed 30/06/2016).

E. J. Greenwood, The Hospital of St Bartholomew Rochester (1962).

R. H. Snape, English Monastic Finances in the Later Middle Ages (1926).

Johannes de Westerham, Custumale Roffense, from the original manuscript in the archives of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester, etc, edited by John Thorpe (1788).

If you would like any further information on Custumale Roffense please feel free to contact me.