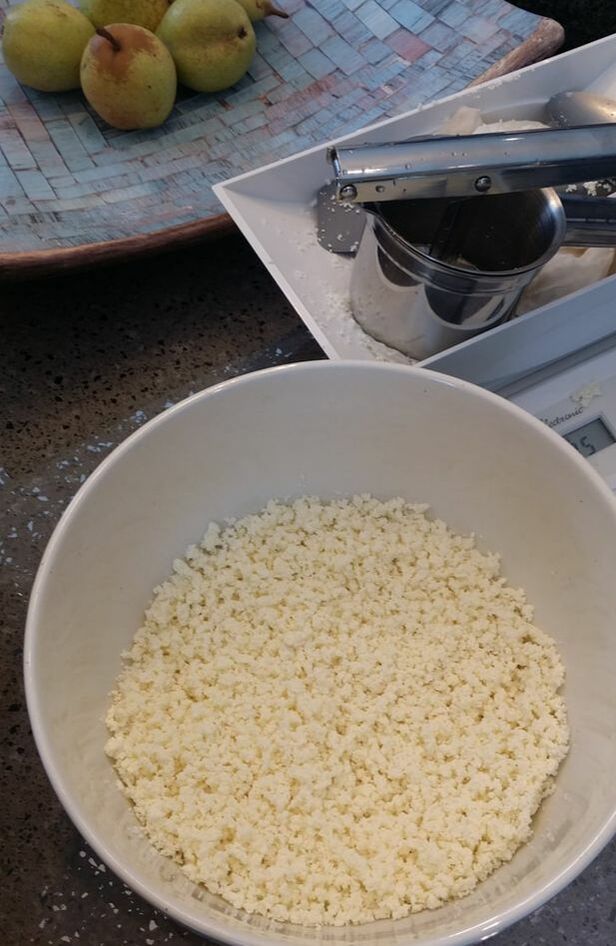

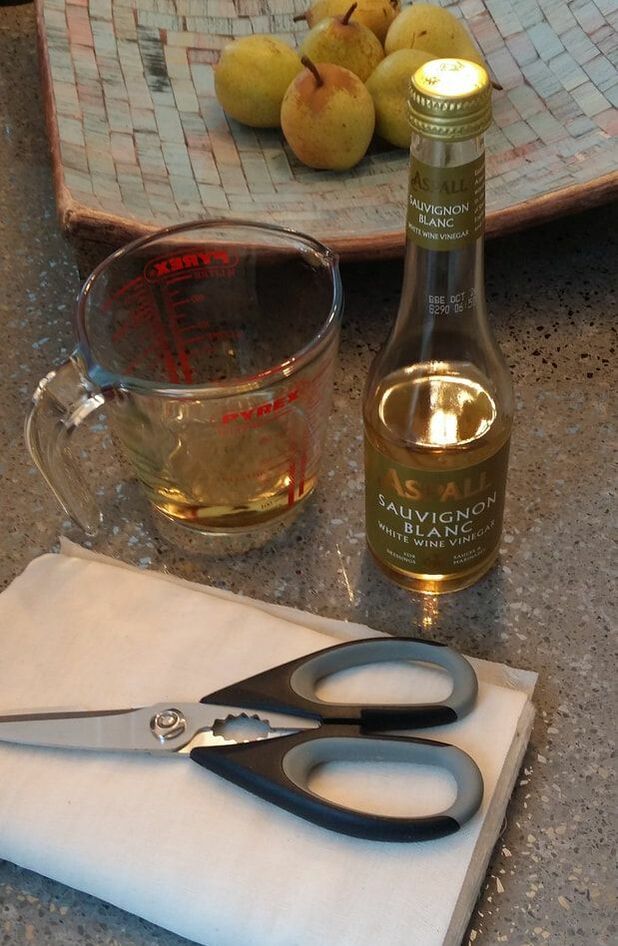

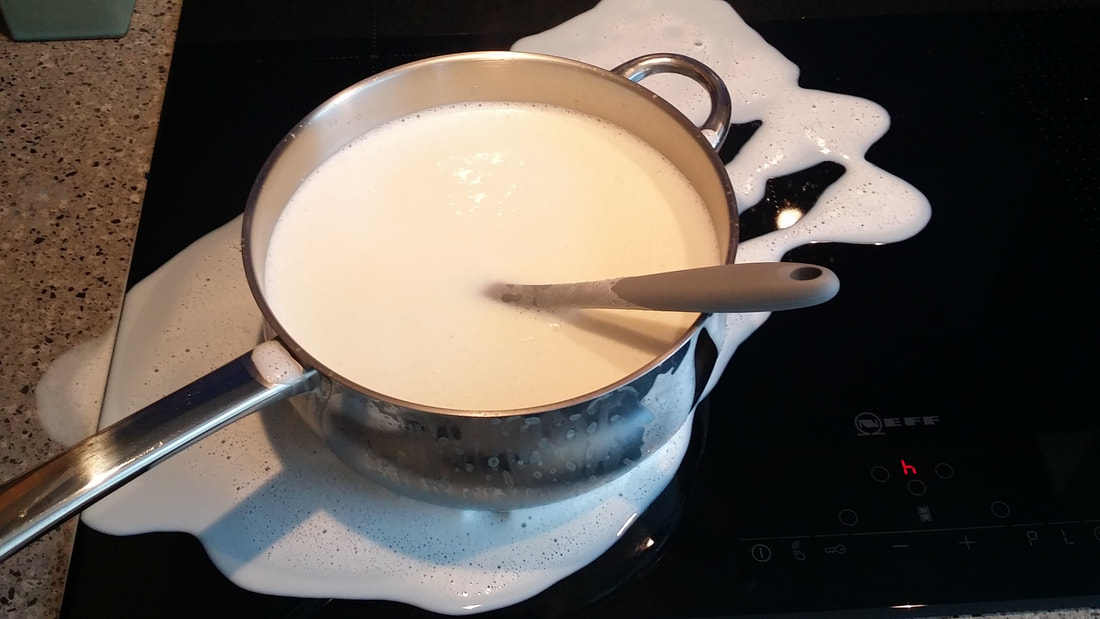

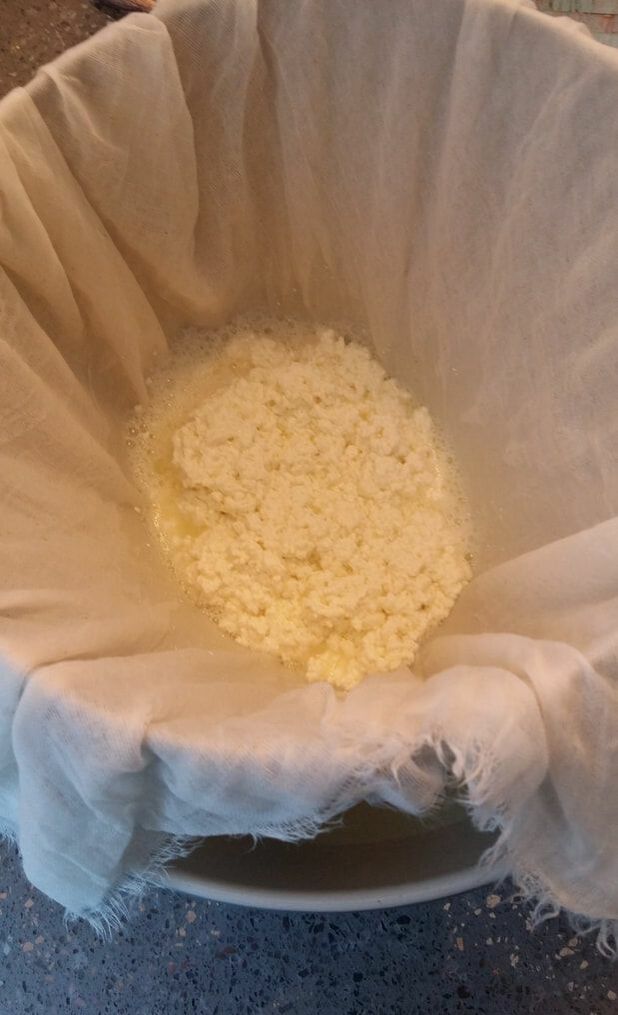

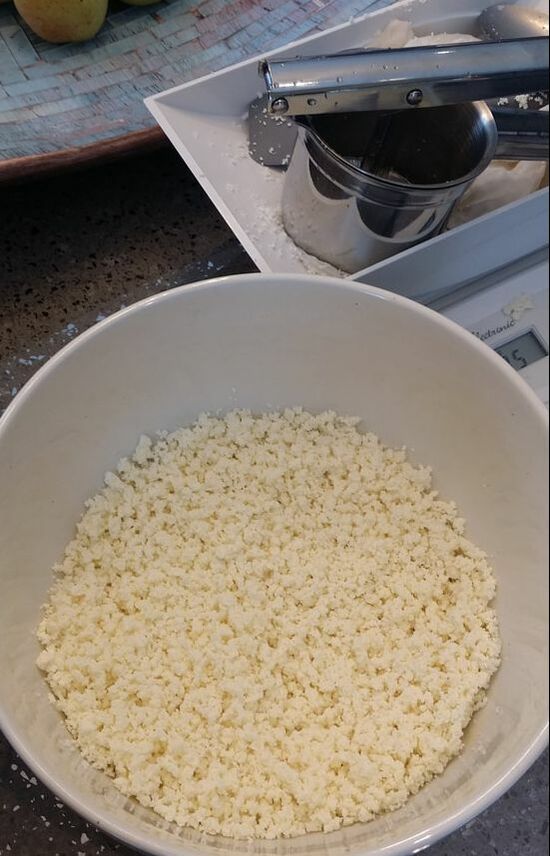

Tak cruddes and wryng out þe wheyȝe & drawe thorow a straynour. The passage above is from recipe 169 in Forme of Cury, the cookery book produced by the master cooks of King Richard II (r. 1377-1399). The recipe goes by the name Sambocade, which derives ultimately from Latin sambucus, meaning 'elder tree'. It is for an elderflower curd tart (or cheescake, if you like). I first attempted to recreate this recipe about 10 days ago. For ‘curds’ I used a really nice organic cottage cheese, which is a curd cheese, but found it just a hint too salty for a sweet dish. So yesterday I decided to make my own, unsalted, curds, which is what the cooks in Richard II’s kitchen would have done. How did I do this? It was really not that difficult. If you wish to try making curds yourself, you will need two ingredients: non-homogenised whole milk (which likely means you will need to look for organic milk, though some organic milk is homogenised) and something acidic like lemon juice or wine vinegar. I used white wine vinegar because lemons were not readily available in fourteenth-century England, and I'm trying to be as authentic as possible in terms of ingredients. You will also need some cheesecloth (muslin) with which to drain and squeeze the curds once they're formed. For about 300g (10½ oz) of curds, you will need a 4 pint carton of whole milk (equivalent to 2.27 litres and 4.8 US pints). Heat this in a large pan until just about to boil and then turn down to a gentle simmer. Be careful – milk quickly goes from steaming and frothing to spilling all over your hob (as I found out!). Next, gradually add the wine vinegar. I used 50ml (1.75 fl oz), but you may need to add more; but don’t keep adding more once the curds form. What you are looking for is for the curds to separate from the whey; this happens within a minute or two. In the picture below you may be able to see it just starting to happen. The acid in the vinegar causes the milk proteins (caseins) to separate from the watery whey, forming clumps of curds. Once this happens, you need to strain the curds through cheesecloth. I prepared the cheesecloth ahead of time by pouring boiling water over it (to sterilise it) and then, when cool enough, I used it to line a colander, which I stood within a large bowl. Then you need to tie the cheesecloth in order to squeeze out the whey. The easiest way to do this is to first rinse the curds in cold tap water; this not only cools the curds so that you can handle them but importantly removes the vinegar taint. I decided also, just to be sure of removing the last vestiges of vinegar, to soak the bundle of curds in cold water for 5 minutes or so, before giving it a final squeeze. Since you are not making cheese, there is no need to press the curds in any way (you would do this if you were making something like paneer). So at this stage you just need to strain the curds, in order to make the clumps much finer. The medieval recipe calls for a straynour, which may have been something similar to a modern sieve. However, I would suggest using a modern potato ricer (pictured below, top right), as it really is too much like hard work passing homemade curds through a sieve (though easy enough if you’re using cottage cheese). Alternatively, you might choose to whizz the curds up in a food processor, but as I haven’t yet tried this myself, I’m not sure what the results would be. The result of using homemade curds rather than cottage cheese was to give a more neutral flavour, far better for a sweet dish. To make up the ‘cheesecake’ mixture, I added a few finely ground breadcrumbs, a little cream (not in the medieval recipe but still medieval), sugar, egg whites, elderflower cordial (again not in the medieval recipe but an adaptation that works when the elderflowers themselves are not in season), and a tiny amount of rosewater. Baked inside a rich butter shortcrust pastry, it really was delicious. I will be filming a recreation of the curd tart in due course and posting at a later date the full recipe. In the meantime, here’s the recipe in the original Middle English alongside my own translation. (Please note both edited text and translation are copyrighted, so please don’t simply cut and paste the information in order to share, but rather share the whole blog post.) Sambocade[1]

2 Comments

|

Details

AuthorDr Christopher Monk is a medieval culture specialist working in the creative industries and heritage sector. Archives

August 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed