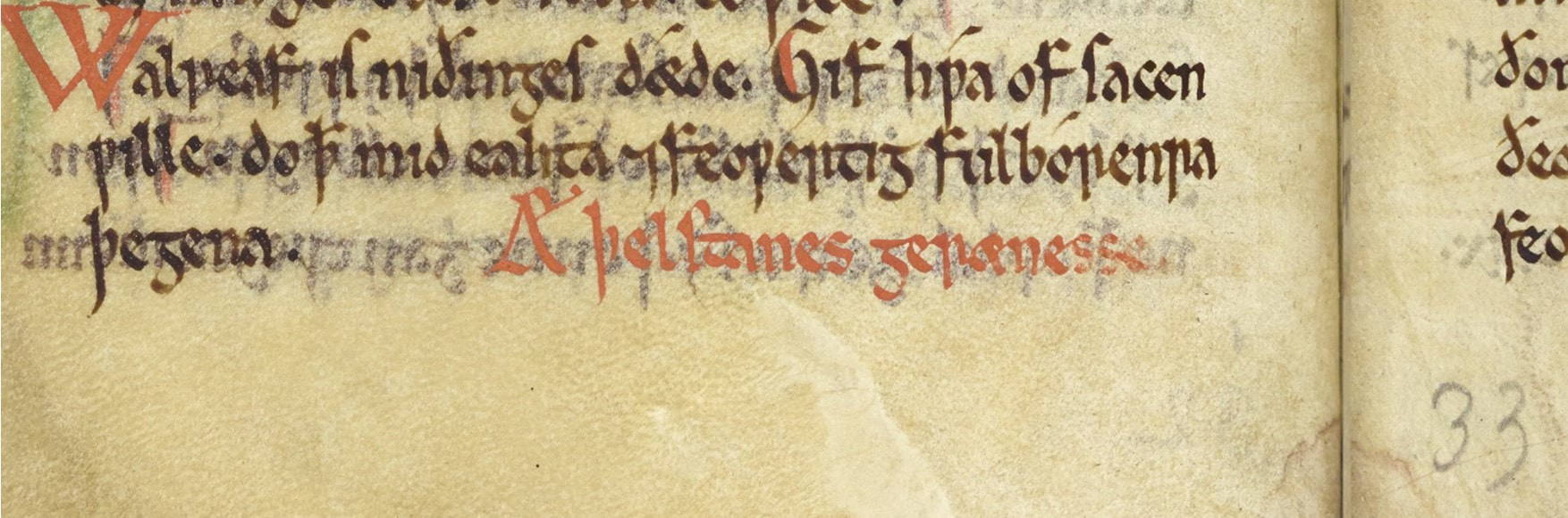

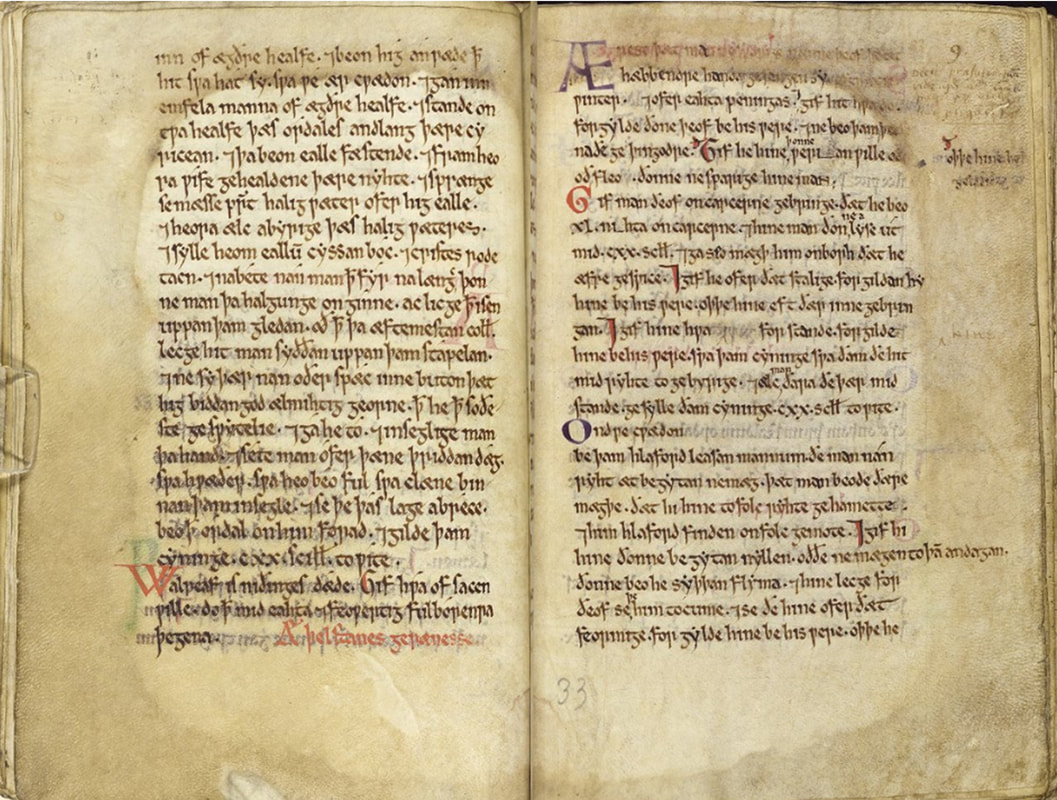

The Medieval Monk casts his eye over the new translation of King Æthelstan's laws  Æthelstan’s Grately Code. It begins with the title ‘Æþelstanes gerænesse’, ‘Æthelstan’s laws’, in red ink at the bottom of the left page (see detail below). Textus Roffensis, folios 32v-33r, Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral. The Grately Code continues for a further eight pages, as far as folio 37r. Screenshot of digital facsimile, Manchester, John Rylands Library. Blessed ones, I bring you a bounteous supply of Old English laws. What more could you ask for? Don't answer. The other Monk of this website, Dr Christopher Monk, has been busy transcribing and translating more material from Textus Roffensis, the fullest set of early medieval English laws written in the vernacular. There are three new translations, the main one being the major set of laws by King Æthelstan, 'king of the Anglo-Saxons and Danes', 924/925-927, and 'king of the English, 927-939. This text is known today as the Grately Code. The other two laws, produced around the same time as the Grately Code, are anonymous and much shorter: Be blaserum ⁊ be morðslihtum, which is all about dealing with nasty arsonists and murders; and Forfang, a fragment from a law concerning the reward for retrieving stolen property. Now Dr Monk, in his introduction to the Grately Code, highlights a couple of important aspects of Æthelstan's foundational law. He talks about trial by ordeal and the phrase 'disobedience to the king'. Yes, yes, all very good. But to my mind there are two really important laws that seemed to have escaped his notice. So read on, beloved ones. Selling horses No person may sell any horse overseas, unless he wishes to gift it. (Grately Code) Now, let me tell you a story. Our tenth-century 'king of the English' didn't mind accepting a gift horse, or even ‘many’ a gift horse, from over the gannets' bath, or whale road, or whatever you want to call the sea. Indeed, according to William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1120s, Hugh the Great, ‘king of the Franks’ – well, actually, he was a duke, Willy – wanted to wed Æthelstan’s half-sister, Eadhild. So to seal the deal with this princess, ‘in whom the whole mass of beauty, of which other women have only a share, had flowed into one by nature’ – you can see Willy Malmesbury setting things up here very nicely, can’t you? – Hugh sent an embassy across the swan road to the king to strike a bargain for the betrothal, not troubling himself in person, of course. Well, Willy tells us his delegation ‘produced gifts on a truly munificent scale, such as might instantly satisfy the desires of a recipient however greedy’ – what’s he saying about our good king? Well, anyway, what did Æthelstan get in return for handing over his beloved, all-too-beautiful sister? ... the fragrance of spices that had never before been seen in England; noble jewels (emeralds especially, from whose green depths reflected sunlight lit up the eyes of the bystanders with their enchanting radiance); many swift horses with their trappings, ‘champing between their teeth’, as Virgil says, ‘the tawny gold’; an onyx vessel so modelled by the engraver with his subtle art that one seemed to see real ripples in the standing grain, buds really swelling on the vines, men’s figures really moving, shining with such a polish that it reflected the face of the beholder like a mirror; the sword of Constantine the Great, etc, etc, etc, etc.’ And I thought I went on some times! But if you're desperate to know what else was given... There was one of the nails of the cruxifiction, attached to the pommel of Constantine's sword; Charlemagne's lance; the banner of Maurice the martyr; a piece of the Cross enclosed in crystal; a bit of the crown of thorns; and a solid gold crown which was 'yet more precious from its gems, of which the brilliance shot such flashing darts of light at the beholders that the more anyone strove to strain his eyes, the more he was dazzled and obliged to give up'! Oh, for Heaven's sake, Willy! We get it! Dazzling stuff. Thankfully, Willy does eventually tell us that King Æthelstan was delighted with his gifts – though the horses did make a mess in his court, though no one noticed because of all the dazzling going on (I made that bit up). In response, the king reciprocated ‘with gifts that were scarcely less’ – of course he did. And, moreover, he ‘comforted the passionate suitor’ – so passionate he couldn’t bear the journey himself – ‘with the hand of his sister’. Aw, lovely. So, there you go. Gifting and receiving gifts of horses was fine. But no horse trading overseas. Why exactly, we are not told in the Grately Code. Possibly it was something to do with the importance of horses to the internal economy of England; or it was that horses were in short supply and needed by the army (Cronenwett, p. 109). Sunday tradingAnd [we declared] that there be no trading on Sunday. If then anyone does this, he should forfeit the goods, and pay 30 shillings as a fine. (Grately Code) Now, there are the crimes of arson, murder by witchcraft, and treachery to one’s lord, but Sunday trading! Well, that really takes the biscuit, as the other Monk would put it. I do hope his biscuits weren’t bought on the Sabbath day. He didn't say. You see, what could be more unchristian than labouring – nay, trading – on the Lord’s day? Never mind treachery to one’s earthly lords, I think that such behaviour amounts to far worse. And if I had written the Grately Code for Æthelstan, I would have sent all offenders straight to the threefold ordeal (you can learn more about that from Dr Monk’s introduction). That’s all I have to say on the matter. Now, where did he put those biscuits? Chocolate, gluten free, they were. Cited works Cronenwett, Philip Nathaniel, 'Basileos Anglorum: a study of the life and reign of King Athelstan of England, 924-939' (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 1974); available here. William of Malmesbury, The Deeds of the English Kings, edited and translated by R. A. B. Mynors (London: The Folio Society, 2014).

0 Comments

|

Details

|