|

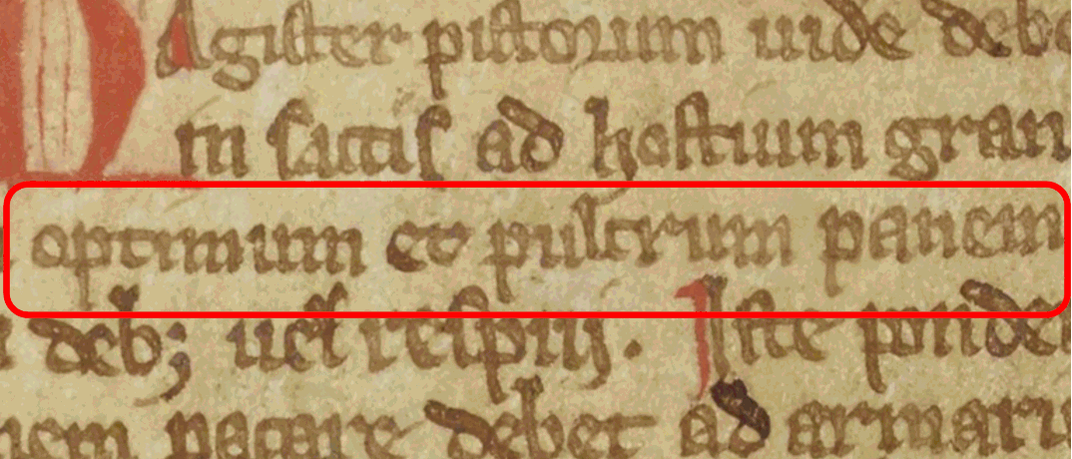

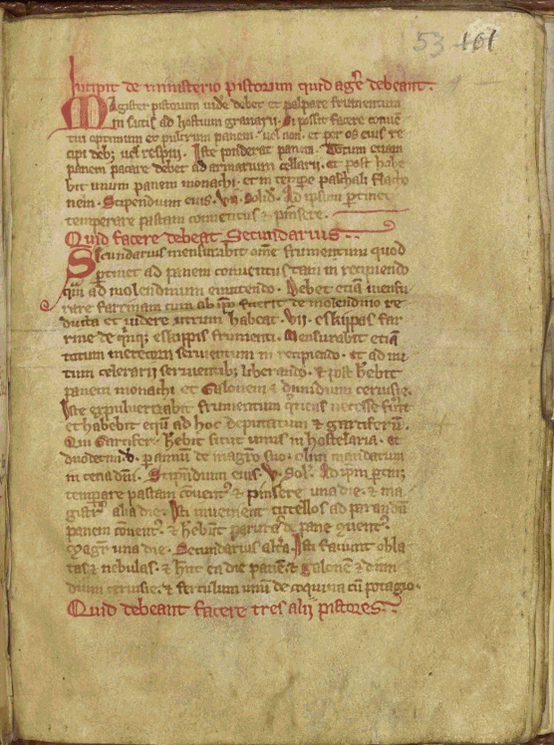

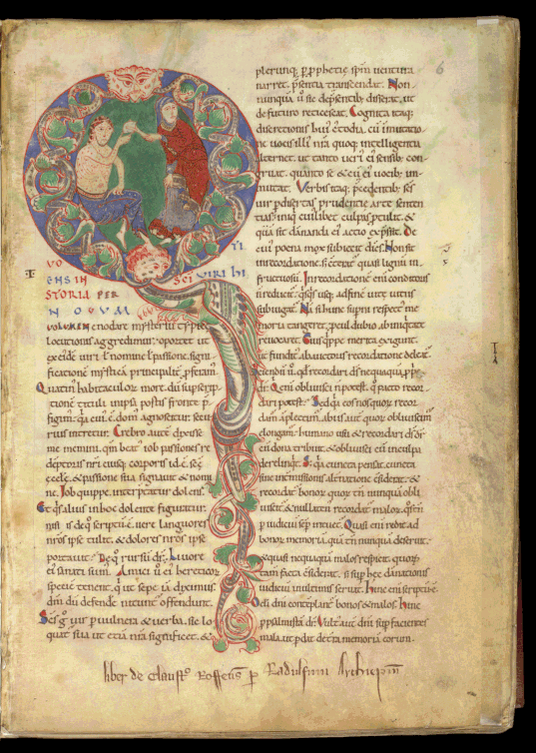

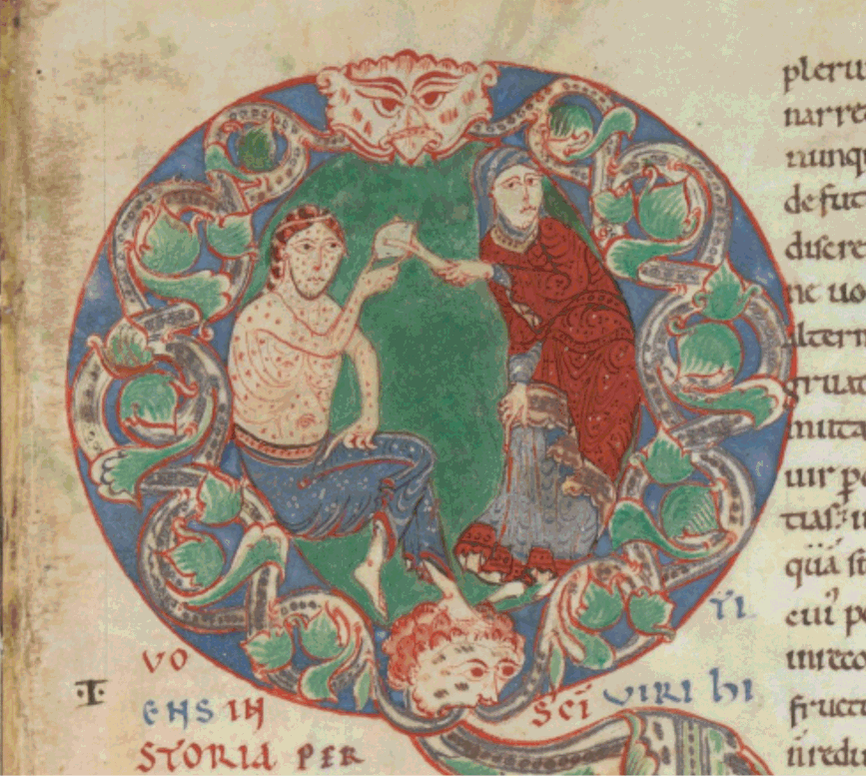

The Anglo-Saxon Monk takes a closer look at the bread of Rochester's Benedictine monks Blessed readers, It is such a busy life being holy, I can tell you. I've been so busy just recently that it seems like I've hardly found a minute to venture beyond my eleventh-century world of Psalm singing, kitchen duties, and scraping calf skins clean for the master illuminator. The abbot has hinted to me more than once that I'll get his job one day; but, in the meantime, I'll have to make do with being a simple rubricator. I suppose it's not terribly Christian of me to wish his demise, so I strive to maintain at the very least an outward display of patience. No one's perfect, blessed ones. But I digress. The good news is that, despite all my travails, I did manage today to sneak a peek at one of my favourite twenty-first century blogs (I say 'one of' because this blog is my most favourite. Obviously!): The Early English Bread Project, written by professors Debby Banham (University of Cambridge) and Martha Bayless (University of Oregon). Their latest blog post initially quite shocked me with its proclamation of 'Christ as an allergen'. But as the authors point out, in view of your Pope's recent decree banning gluten-free communion bread, there does appear to be at least some truth to their assertion. Perhaps this explains the general lack of spirituality on the part of my alter ego, the other Monk. All this time I've been judging him as a disreputable fellow, when in fact it is probably his gluten intolerance that is holding him back. I'm mortified! Dr Monk is allergic to the body of Christ! May the Lord have mercy. But I digress once more. What I wanted to say was that all this reading about bread, holy and mundane, has started me thinking about my brothers of St Andrew's Priory in thirteenth-century Rochester. I remember Dr Monk telling me about the Rochester customs book which one of the monks compiled, and its description of the servants my fellow Benedictines had at their beck and call within the monastery precinct, including the millers, who were also bakers. Now what did it say about bread? 'Concerning the office of the millers: here is what they ought to do Carefully note, blessed ones, the requirement to make 'the best and finest bread' for the monastery. I can tell you, that is not a prerequisite for my own 'monk's loaf'. I'm lucky if I get some oat flour or barley flour in mine, never mind the best wheat. Thank heavens for the weevils. At least I get some protein. As the authors of the Early English Bread Project point out, the best bread in Anglo-Saxon times was made from wheat, and this is the case in later medieval England, too. And it would seem that our Rochester Priory master miller even had the skill to identify the best grain just by tasting it, which is what is meant by 'even by his mouth he ought to accept or reject it'. By the way, if you're wondering what a flaco is, you might wish to read my blog post on medieval treats. It always gets me salivating. I do apologise. Now, what about holy bread used for communion. What does the customs book say about it? Was extra special flour used? Does it say that it should be unleavened? Well, it's rather vague: 'What the second rank [miller] ought to do As you can see from the quotations above, the emphasis is rather more on the nutritional arrangements for the servants than our blessed Lord's body. Nevertheless, we are told that both concecrated loaves (Latin, 'oblatas') and wafers (Latin 'nebulas') are made. Communion bread in the Western Church was unleavened (made without yeast). Though this is not stated in the customs book, it was probably understood as a given: it is not, after all, a recipe book we're reading here. That there are two forms of holy bread, loaves and wafers, most likely refers to the altar bread used by the priest and the communion wafers fed to the blessed laity. The distinction of larger and smaller communion loaves is still preserved in your time by the Roman Catholic Church. I am relieved somewhat that this description of the miller-bakers' duties does end on a spiritual high: the first loaf that is weighed out (by the master miller) is Christ's. Thank heaven for that! I was beginning to think my blessed brethren of Rochester had lost the plot. Indeed, blessed ones, let us all remember that there is more to this life than consuming physical bread, even if you are so fortunate enough to enjoy the finest and best. There is also, by the grace of our Lord, the bread of eternal life to partake of. Now, what did I do with that recipe for flaco? Post scriptum... I thought, blessed ones, you might wish to look at the bread-related image below, from a manuscript produced at the priory in Rochester. Rather thought-provoking.

0 Comments

|

Details

|