Marriage in the Christian West wasn’t always as it is often conceived today, and the way it developed among the Anglo-Saxons is a good way of illustrating this. Unless by means of some kind of trans-historical time warp you have been living in early medieval England, you can’t have failed to notice the ongoing religio-political hoo-hah about gay marriage. Mind you, if you had been alive in the so-called Dark Ages, there was a good chance you would have known more about the development of marriage than many of the more, shall we say, noisy orators appear to know today. If you have ever stopped to think about marriage in a historical context, you may have assumed that the Church had the monopoly on the institution. We do, after all, call it the sacred institution of marriage – though that also has something to do with the idea of God instigating marriage: Adam and Eve, two becoming one flesh, and all that marvellous stuff. But it may come as a surprise to learn that the early English Church had a tough time getting its members to conform. For example, it is remarkable how long it took for the Church’s disapproval of polygyny (having more than one wife) to influence secular law. Even though Christianity came to England by the end of the sixth century, and relatively swiftly became the official religion of its people, there is significant evidence that polygyny, in the form of concubinage, continued as a practice throughout most of the Anglo-Saxon period. Remarkably, though the Church progressively became more involved in the formulating of laws, there is no law explicitly outlawing multiple wives until King Cnut legislated against having both a wife and concubine in his laws (1020-23). Whitred's Code (695) does warn men who are 'in an unlawful sexual union' to repent and foreign men to 'set their union to right' but these terms are somewhat vague and their is no explicit reference to multiple sexual partners here (e.g. a wife and a concubine). There was, as far as the Church was concerned, an issue of marrying a 'close' relative (e.g. one was not allowed to marry a first or second cousin), and so the 'unlawful' union of Wihtred's law may well have been referring to that. Now since there are extant Anglo-Saxon laws dating back to the seventh century, that makes nearly four centuries of Christian culture in England without a single mention in these laws about the typically un-Christian practice of polygyny that was being practiced during that time. Oh, by the way, good Christian King Cnut had two wives himself: he was informally married to Ælfgifu of Northampton (1013) and legally married to Emma of Normandy (1017). We should no doubt call him a hypocrite, though I think it’s worth pointing out that a certain Archbishop Wulfstan of York (died 1023) probably had the king’s arm up his back, as it was the archbishop who actually wrote the law on behalf of his monarch. Now I don’t wish to suggest that the Church sat silent on the matter of polygyny until this law was passed. No, indeed. Both the great religious scholar Alcuin (died 804) and the abbot and homilist Ælfric of Eynsham (died c.1010) made their thoughts on concubinage very clear by stating that Christians weren’t to imitate the example of the Old Testament patriarch Abraham, who had both a wife, Sarah, and a secondary wife, or concubine, Hagar. So, from their point of view, it was to be only one wife for all. (Ælfric, by the way, was always rather nervous about ‘dizzy’ laypeople misinterpreting the Bible, especially the Old Testament, particularly on matters to do with sex – and yes, he did use the word ‘dizzy’!) Further, in Wulfstan’s Canon Law Collection (a collection of Church decrees taken from numerous continental works of the ninth and tenth centuries), the perspective of the church father Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430) is forcefully reiterated: Concubinage 'numquam licuit, numquam licet, numquam licebit' (has never been permitted, never is permitted, never will be permitted)! And then there are the penitentials – the books used by priests both as a teaching aid and a guide on matters of confession. They speak authoritatively against concubinage. Or do they? 'The man who has a lawful wife and also a concubine: no priest shall give him the Eucharist, nor perform any rites which one does for Christian men, unless he should turn to repentance. And if he has a concubine but no lawful wife, he should take charge of that to do as he thinks; nevertheless, he should know that he should have keeping of one, be it a concubine, be it a wife.' The Old English Penitential (probably tenth-century) 'He who has a wife and also a concubine: let no priest perform for him any rites associated with Christian men, unless he turns to repentance; he should have keeping of one, be it wife, be it concubine.' The Old English Handbook (probably early-eleventh-century and associated with Wulfstan) It seems there was a bit of fudging going on when it came to marriage in Anglo-Saxon England. The first canon appears to give permission for a man to keep a non-legal wife or concubine as long as he does not also have a lawful wife. The second implies that he can choose a concubine over a wife. Neither has the spirit of Augustine’s condemnation of all concubinage. It would appear, therefore, that on the matter of marriage there was a degree of compromise on the part of the early English Church, most likely because the practice of concubinage was not relinquished easily by Anglo-Saxon elite men. You may be wondering why I mentioned at the outset the debate about gay marriage. Well, to add to this debate my own tuppence worth (as my grandma would have put it), I hope my historical observation about marriage and concubinage demonstrates that marriage hasn’t always been as fixed as people often imagine or claim – even in Christian communities. On the contrary, attitudes have varied and shifted; ideas about marriage have evolved over centuries. This even goes for the wedding itself. At one time in Christian England, the Germanic tradition of a man taking home a woman (followed by the couple having sex) was most likely all that constituted the ceremony of marriage. The Old English word rihthæmed, signifying a lawful marriage, actually derives from the word for home (the hæm bit), suggesting that this was indeed the origin of English marriage ceremonies. Furthermore, Christian couples didn’t necessarily feel obliged to be married inside a church by a priest. The Anglo-Saxon Church wanted them to, as certain penitentials show, but it took centuries before this requirement became enshrined in English secular law; and, significantly, well after the Anglo-Saxon period. I guess what I am saying is that today’s ideas about marriage, various and complex as they are, have a sort of foundational history, though I'm not saying that the concept of gay marriage grew out of Anglo-Saxon England, for it appears to have been unheard of in early medieval England. So how might all of this talk about early medieval marriage affect the way we conceive of marriage today? Well, as we know, some gay people want to formalize their union, some do not; some straight people want to marry, some do not; some Christians – not all – feel anxious about marriage being undermined by non-normative unions. No doubt Anglo-Saxon concubinage, were it practiced openly today by Christians, would ruffle a few feathers. Perhaps by reflecting on the historical contexts of marriage, it may just help us to appreciate that diversity in marriage has a long tradition. The arrival of gay marriage may then be seen to reflect or continue that tradition. We may personally feel uncomfortable with gay marriage. Or even as a gay person, it may be that we wouldn't actually choose it for ourselves (yes, not all gay people like the idea), but hopefully the history of marriage in Anglo-Saxon England may just help us realize that gay unions are not the first queer marriages to appear. Useful reading: Margaret Clunies Ross, ‘Concubinage in Anglo-Saxon England’, Past and Present 108 (1985), 3-34; Conor McCarthy, Marriage in Medieval England: Law, Literature and Practice (Boydell, 2004); Pauline Stafford, Queens, Concubines and Dowagers: The King’s Wife in the Early Middle Ages (Leicester University Press,1998) Go on ... have your say by leaving a comment.

0 Comments

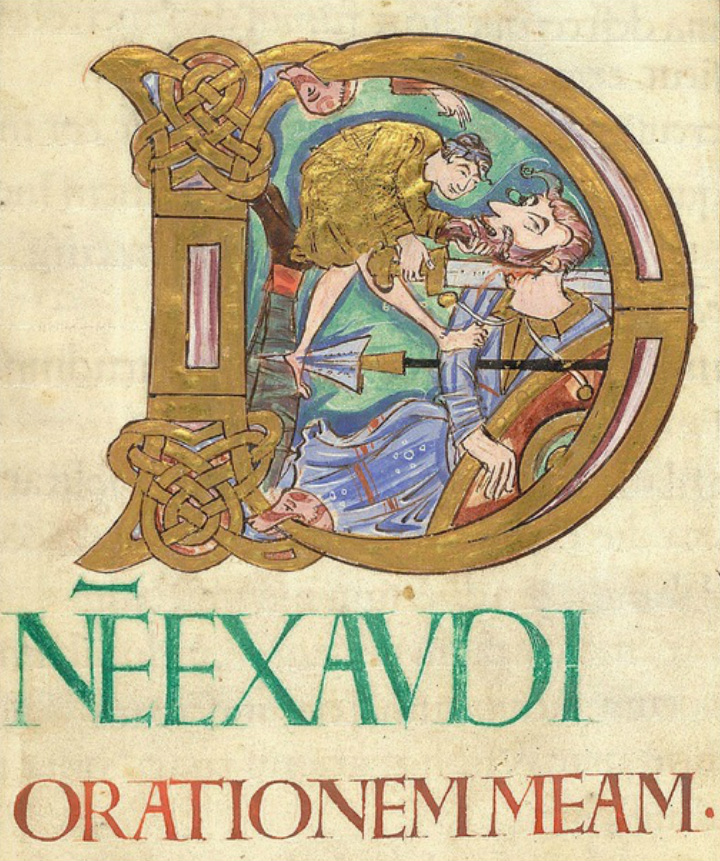

Living up to it. Challenging it. Laughing at it. Manhood is a curious thing. And how do we define it? Is it about moral courage, for example? Or is it simply a matter of virility? My guest post for Manchester Medieval Society asks whether any of our preoccupations about manhood were shared by the Anglo-Saxons.  Now I don't want anyone thinking the Anglo-Saxon Monk is tight, or a bit of a stingy old b***er. So I'm making available a number of hardcopies of my 2012 article, 'A context for the sexualization of monsters in The Wonders of the East', written for the premier journal in Anglo-Saxon studies, no less. And what's more, I'm paying for the postage out of my own moth-eaten purse! I'll even sign it if you want! So if you would like a copy, just send me your forwarding address via my CONTACT ME form.  My review of Asa Mittman and Susan Kim's book Inconceivable Beasts is now available for free. Read it at The Review of English Studies. If you read my blog a few weeks ago, you may remember that Mittman and Kim suggest one of the monsters in the Beowulf manuscript is wearing an ape-suit! Read: Is this an Anglo-Saxon ape suit?  Gerald of Wales (1146-1223), in his portrayal of Ireland, allowed his rather fervid imagination to get the better of him. The bearded woman of Limerick, described in his Topography of Ireland, was his way of using 'abnormal' gender to frame the Irish as wild and unruly. (British Library Royal 13, B. viii, folio 19r: identified as free of known copyright restrictions) Gerald of Wales (1146-1223), in his portrayal of Ireland, allowed his rather fervid imagination to get the better of him. The bearded woman of Limerick, described in his Topography of Ireland, was his way of using 'abnormal' gender to frame the Irish as wild and unruly. (British Library Royal 13, B. viii, folio 19r: identified as free of known copyright restrictions) IF YOU'VE EVER thought that the question of gender identity is a modern phenomena, think again. Back in the tenth century, the Anglo-Saxon Church created what we might call 'gender trouble'. In a sense, the Anglo-Saxons even had a word for it ... To really get into the mindsets of people who lived hundreds of years ago, it's important to understand how people used language. Perhaps only then do we grasp the nuances of their lives and thoughts. Sometimes understanding a single word or an idiomatic term can open up cultural meaning. A case in point is the Old English word bædling, which appears in a penitential text known today as the Old English Canons of Theodore. (Penitentials, by the way, are handbooks that were used by priests to help them decide how much penance should be done for a particular sin – great weekend reading!) This Old English text goes back at least to the end of the tenth century and possibly much earlier. It wasn’t as the title suggests authored by Theodore, who was a seventh-century Archbishop of Canterbury. Rather it was an English version of a compilation of Latin judgments attributed to him, a text now known as the Penitential of Theodore (or, as I like to call it, Theodore's Greatest Hits). I emphasize here version, because though clearly the Old English penitential owes a great deal to the Latin, it would be erroneous to think of it as a translation in the modern sense. The writer of the Old English Canons (we don’t know who that was) reorganized quite a bit of the material, did a little adding and quite a lot of subtracting, tweaking and interpreting. It was like that back then. So where does the word bædling fit into all of this? Get to the point, Anglo-Saxon Monk! Well this extremely rare noun is a really important word for helping us think about the way Anglo-Saxons may have thought about gender and gender identity. A bædling, to try to put it into modern parlance, was someone who had 'gender trouble' – at least from the perspective of others. The bædling is mentioned in a series of pronouncements about 'deviant' sexual practices: one of the canons prescribes the very steep penance of ten years of fasting for a man ‘who has sex with a bædling, or with another male, or with a beast’. We should note that a bædling is not considered here to be ‘another male’: this one doesn’t qualify as a wæpnedman, to use the marvellously euphemistic Old English word from the canon, literally meaning a ‘weaponed man/person’. (I don't think I need to spell out the euphemism.) Then two canons later there is another reference, where ten years of fasting is also handed out to the bædling who has sex with another bædling. A little bit of explication is then offered by the canonist: ‘They [the bædlings] are soft like a harlot’! Umm ... I think it’s pretty obvious that bædling is not a particularly friendly term: it wasn’t chosen by the individuals concerned; it was imposed from on high, so to speak. But it must have been a recognizable term. It's distinctly English, not directly corresponding to any word in the Latin source text. A bædling appears to have been the way this English canonist conceived of someone not fitting into the biblical binary of ‘male and female he created them’. One scholar, R. D. Fulk, has suggested bædling may derive from the word bæddel, corresponding to 'hermaphrodite', which leaves the possibility that the bædling was viewed as some kind of descendent or associate of a mixed-sex (or intersex)person. ('Hermaphrodite', by the way, is not exactly a friendly term either.) Interestingly, the -ing suffix is used in Anglo-Saxon genealogies, and poetry too, to signify 'the son of'. So the bædling may have been used in a similar way, to mean the son of an hermaphrodite. Leaving aside the issue of forbidden sexual intercourse, which is the only reason the bædling gets a mention in the first place in this penitential, I often wonder if all of this was a philosophical or theological problem for the ecclesiasts of the day: what to do with these pesky persons who don’t fit into a nicely and divinely ordered gender system! It’s interesting that another Anglo-Saxon text, Liber monstrorum (book of monsters), written probably around the turn of the eighth century, has as its first monster a person who appeared physically, from his upper body, to be more like a man, but who enjoyed being and living as a woman. So, I guess, one solution for some Anglo-Saxons was to think of atypically gendered persons as monsters! All this very much brings to mind the problem many of us may have today dealing with people who don’t fit neatly into narrow prescriptions of gender, transgender people, for example; or, indeed, the related difficultly we may have of handling sexual orientations that don't fit into the 'norm'. I revised this post today because I was rather moved by a video I saw last week, one that you may have seen too, as it went viral. A young man in the US came out as gay to his family, an act that showed he had tremendous courage, as he met with vile abuse from those who should have loved him. Is it not alarming, then, that in many ways we’ve hardly moved on from monsters and bædlings? Let me know what you think. Leave a comment. Useful sources for more detailed discussion of the bædling: David Clark, Between Medieval Men: Male Friendship and Desire in Early Medieval English Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), pp. 58-67; Allen J. Frantzen, Before the Closet: Same-Sex Love from Beowulf to Angels in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), pp. 163-75, and ‘Between the lines: queer theory, the history of homosexuality, and Anglo-Saxon penitentials’, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, 26:2 (Spring 1996), 16-29; R. D. Fulk and Stefan Jurasinski (ed.), The Old English Canons of Thedore, EETS ss. 25 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 66-7; R. D. Fulk, ‘Male homoeroticism in the Old English Canons of Theodore’, in Sex and Sexuality in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Carol Braun Pasternack and Lisa M. C. Weston (Tempe, AZ: ACMRS, 2004), pp. 1-34; and Christopher Monk, ‘Framing sex: sexual discourse in text and image in Anglo-Saxon Englans’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Manchester, 2012), pp. 127-40. For the Liber monstrorum, an edition and translation is provided as an appendix in Andy Orchard’s Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (1995; revised edition, Toronto, Buffalo, NY and London: University of Toronto Press, 2003), pp. 254-317. |

Details

|