|

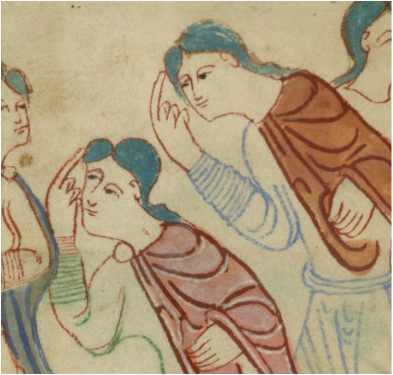

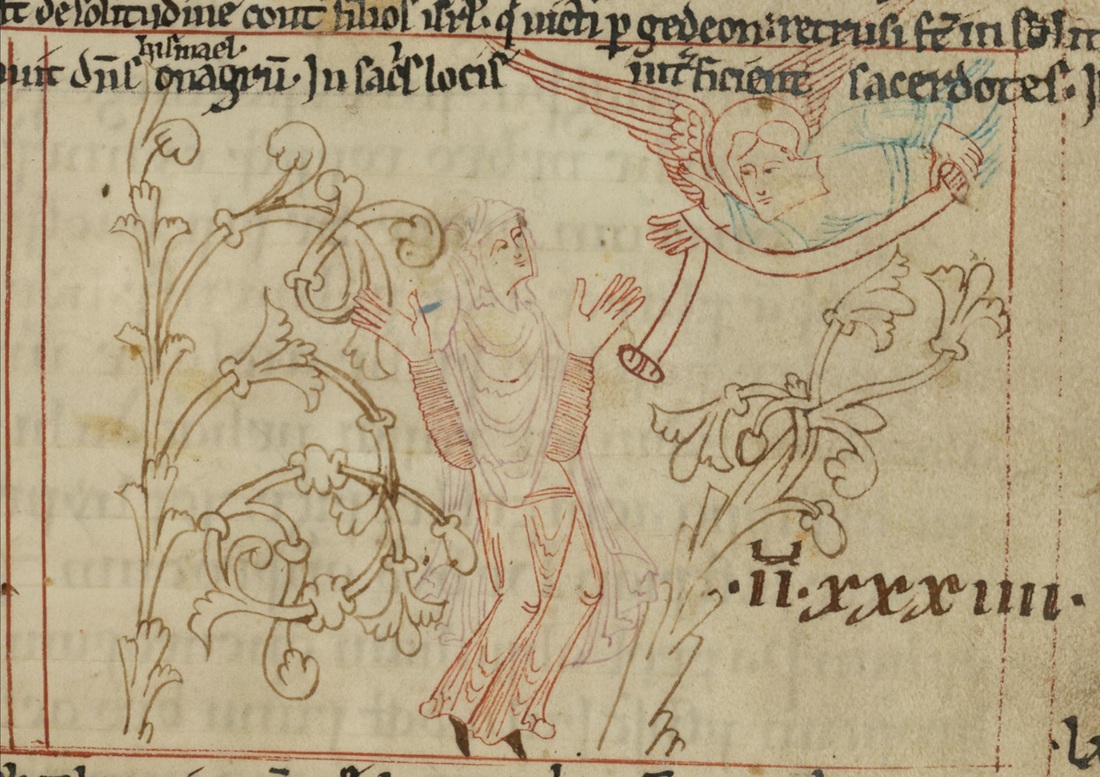

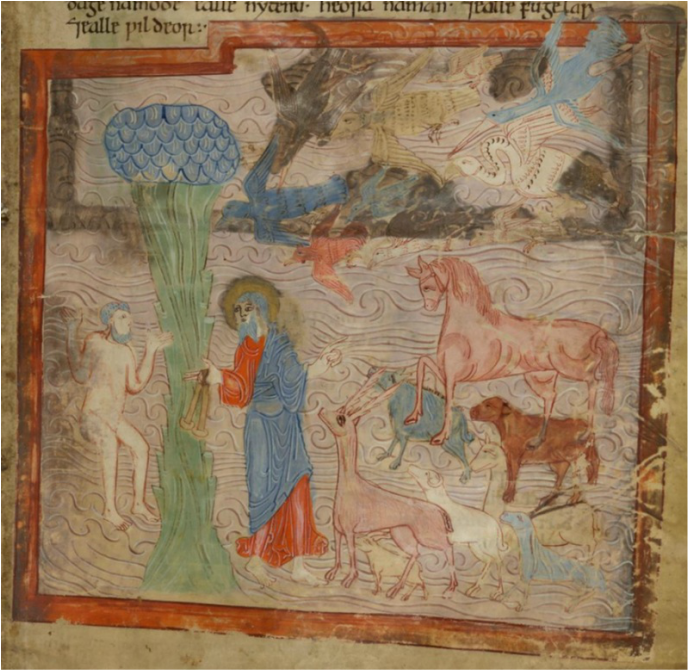

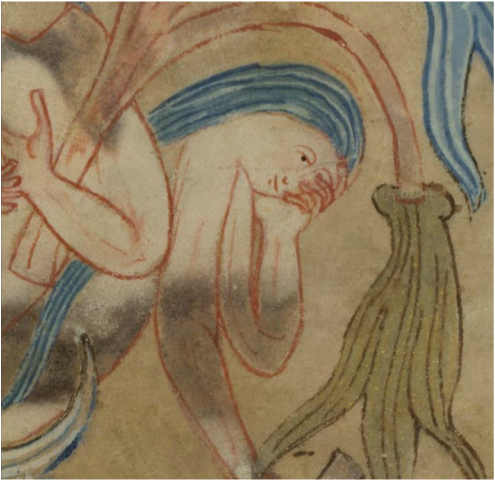

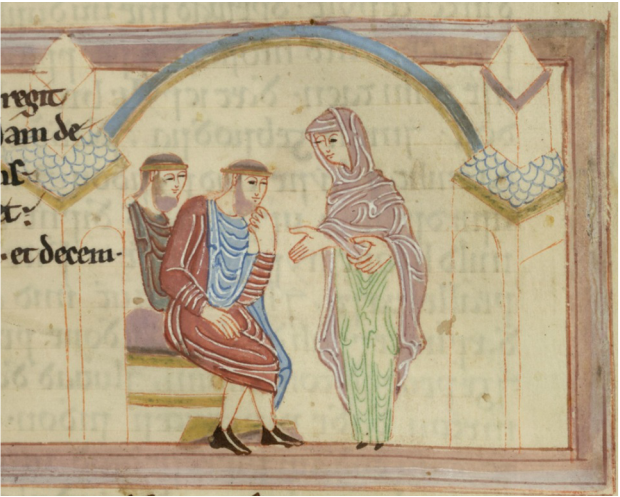

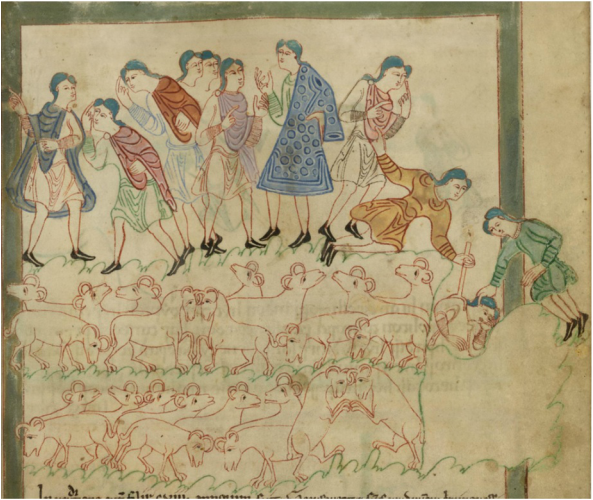

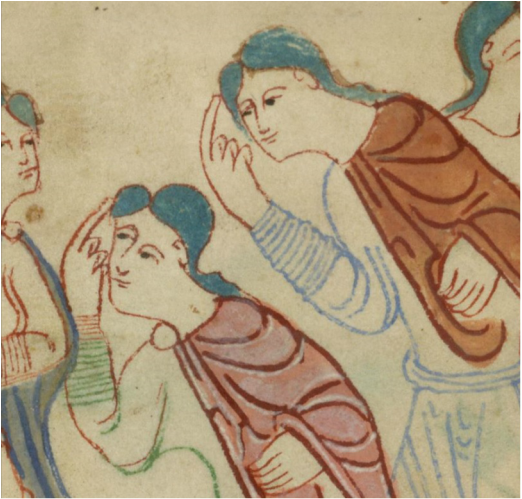

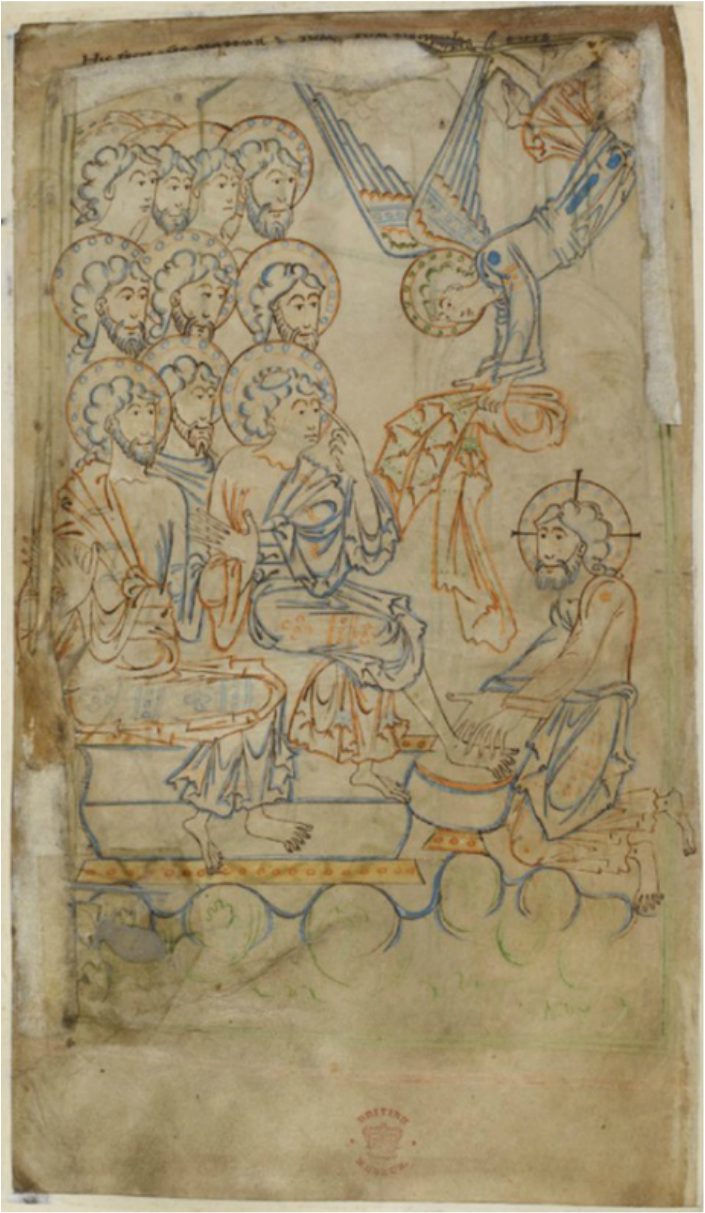

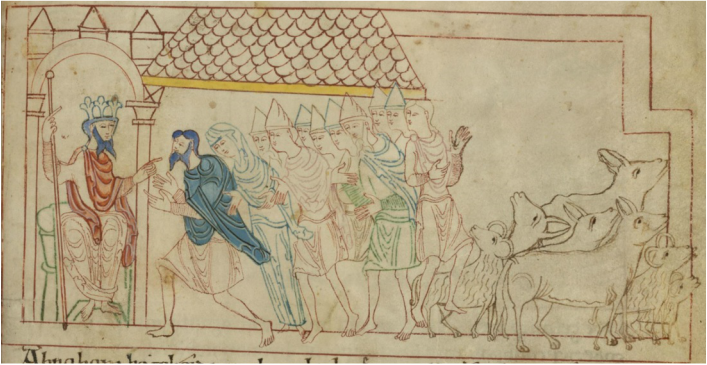

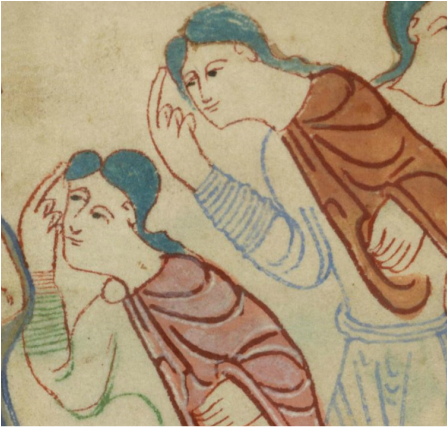

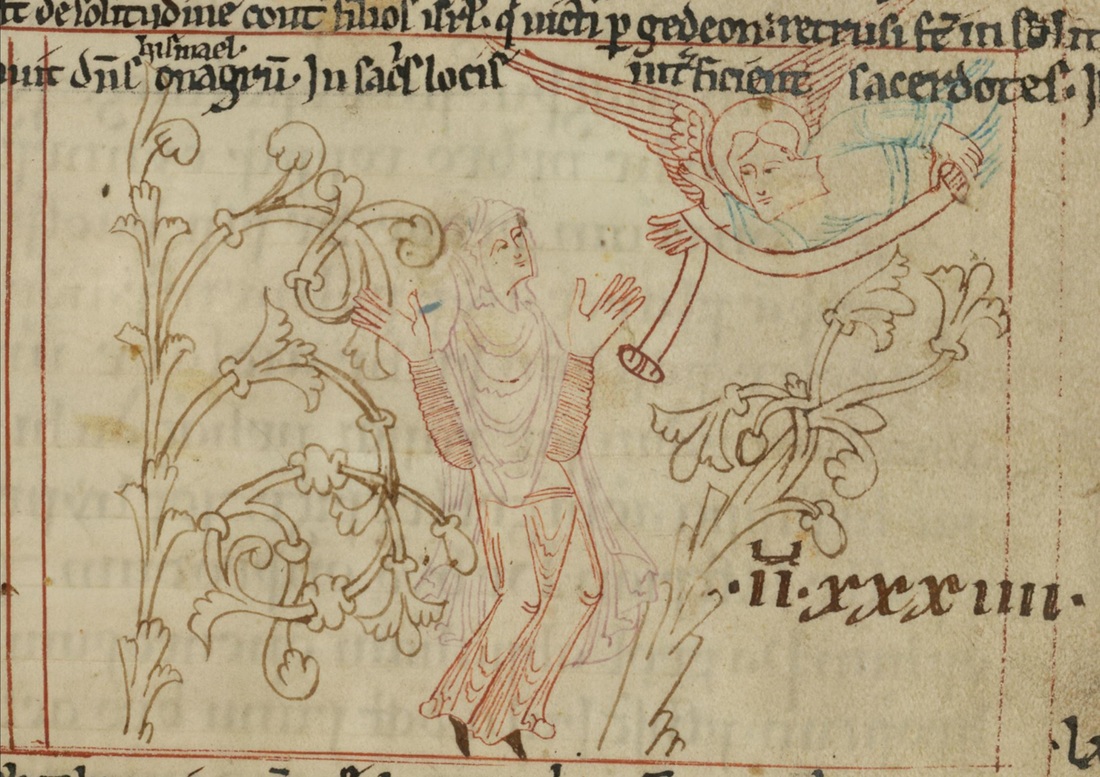

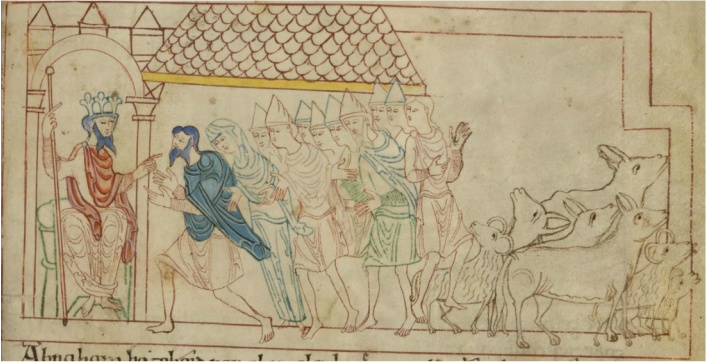

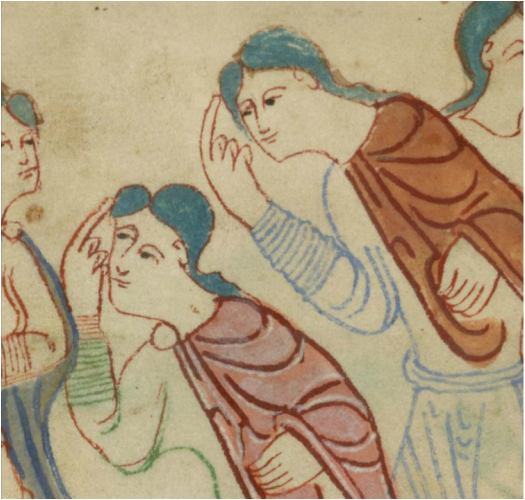

Blessed ones, How did you get on in identifying the emotions on display in the five scenes from Genesis in the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch? A number of you left responses that, quite frankly, left this eleventh-century monk deeply disturbed. But at least you tried, and the Lord loves you all the more for your effort. Here are the actual answers. Each of the five emotions or moods are drawn from Roman stage gestures that evidently were borrowed by the Anglo-Saxon artist. For a detailed study of this, see C. R. Dodwell's Anglo-Saxon Gestures and the Roman Stage. 1 Starting with the easiest. What emotion is Hagar feeling on seeing this angel suddenly appear? Answer: Hagar's open palm gesture represents fear or anxiety. Hagar is walking all alone in the wilderness, because Sarah her mistress has just given her a good old fashioned lashing and she's run away (please read Genesis, chapter 16), when all of a sudden an angel appears to her with a message from the Lord. I think we can forgive Hagar her moment of trepidation, don't you? This gesture is used extensively throughout the Hexateuch. It is often used, for example, when God suddenly appears to a human, such as in the example below, when the Lord asks the newly created Adam to name all the animals. Well, I'd be afraid of God if he looked like that! It's also used in the Junius 11 manuscript, produced a few decades earlier than the Hexateuch, when Ham sees his father Noah lying drunken and exposing his genitals. Anxious indeed! 2 No longer in Eden, what emotion is Eve feeling? Answer: Eve's hand-to-face gesture signifies grief or sadness. Eve is grieving because she's sinned and the Lord has kicked her and Adam out of Paradise. Fair enough. The gesture of grief is frequently associated with death scenes in the Hexateuch. There's a fair bit of dying in Genesis, and typically you see one of the patriarchs completely wrapped up in a cloth, somewhat like a giant sausage, being carried off stage left. One or more of his relatives is shown with the hand-to-face grief gesture. More intriguing, perhaps, are scenes where death is not involved, such as in the Eve scene, and also in the one below, where Isaac, now very aged and excessively myopic, has just realised that he's blessed the wrong son! (For the full story, please read Genesis, chapter 25, verses 19-34; and chapter 27.) Poor Esau! He's fondly waving at his dad ("I'm over here, over here"), expecting to get from him the blessing of the first born, when actually his younger twin Jacob has already obtained it through deception (he tricked Isaac into thinking he was Esau by covering his body in animal furs to mimic Esau's legendary hirsuteness). And there's that shifty Jacob now, niftily exiting out of the picture's frame, cup in hand as a symbol of the blessing. No wonder Isaac looks so aggrieved! But Isaac, lament thee not! For we all know that Jacob is the good son really. Isn't he? 3 Oh Lord! What is Abraham's mood after his wife's servant girl Hagar gives birth to his child? Answer: Abraham's hand to chin gestures shows that he is pondering. It's hardly surprising, blessed ones. Having been asked by his barren wife to impregnate her slave girl Hagar, he's contemplating the future. Believe me, Abraham, the future is full of tension! Though thankfully, the Lord blesses Sarah's wizened womb and lo and behold she provides Abraham with a proper son, Isaac. (Your reading for all this, blessed ones, is Genesis, chapter 16; chapter 18, verses 1-18; and chapter 21, verses 1-16.) There aren't many examples of this gesture elsewhere in the Hexateuch. Perhaps a little more pondering beforehand may have proved quite beneficial to some of the characters in Genesis, eh, Abraham? Here's another example from the Hexateuch, below, this time from the book of Joshua. I won't go into all the details (you can read the story in your bibles at Joshua, chapter 2) but suffice it to say that the two men are Israelite spies, checking out the lie of the land in the city of Jericho, and somehow they've ended up in the house of the prostitute Rahab. This one needs a great deal of pondering, blessed ones. 4 Ignore the sheep! What feelings do these two brothers of Joseph have? (A third brother on the right feels the same.) Answer: The index finger to the head or face indicates puzzlement. Joseph's jealous and mean spirited brothers have decided to get rid of him because he blabbed about their bad conduct to their father (Genesis 37). They've thrown poor Joseph into a pit but now they're not sure what to do with him. Should they kill him? Should they dispose of him by selling him to some passing strangers? You can see what a terrible quandary they're all in, can't you? A fair number of the puzzlement gestures occur in the Hexateuch, including Aaron's, when the Lord tells his brother Moses that his rod will blossom. What?! You can understand Aaron, can't you, blessed ones? One of my favourite uses of the puzzlement gesture is from a later English manuscript, the Tiberius Psalter, produced at Winchester. In the image below you can see that Peter is rather puzzled when Christ washes his feet. Now, is it the Lord's humility that's perplexing him so, or is it in fact that the angel has only just turned up with the towel? 5 What is Abraham's mood before King Abimelech? Is it just me, or do the others have a balance problem? Answer: Abraham's outstretched arms along with his bent legs represent his supplication, or beseeching, before the king. No surprises here, blessed ones, though the story's a bit complicated. King Abimelech is in a great deal of trouble with the Lord who has told him in a dream that he's as good as dead for taking Abraham's wife Sarah as his own wife. But it's all faithful Abraham's fault. He told Sarah to fib to Abimelech that she was his sister not his wife, just in case the king wanted her for himself, which he clearly did, and to prevent the king from killing Abraham, the great man of faith, in order to get her as his wife. (Please read the full account in Genesis chapter 20.) What we see hear is the aftermath, when Abimelech calls everyone to his court in order to extricate himself from his marriage to Sarah. Abraham adopts the pose of a running slave, all deference and appeasement. And Sarah, the princes and pretty much everyone except the animals are leaning in to hear what Abimelech is saying in response, which in short is something like "What did I do to deserve this, you clown?" What a kafuffle! It's not just angry kings in the Hexateuch that merit a moment of supplication. As you would expect, the Lord himself often inspires a bent knee and outreaching arms, such as in the image below of Abraham receiving the Lord's promise that he will become father to a great nation. Well, at least Abraham's not causing trouble this time! Well, beloved readers, are we not truly blessed to have the stories of the Bible come to life through the pages of the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch? The artist is to be thanked that he was capable of tuning in to the real emotions behind the narratives.

Moreover, blessed ones, you now have a wider array of gestures that you can tap into at any appropriate moment. But please avoid those that are as a consequence of upsetting a king or the Lord God himself, sleeping with your wife's handmaiden, or throwing your brother down a pit.

5 Comments

Blessed ones, You must have worked out by now that at times monastic life here in the eleventh-century gets just a little too regular for me. I need diversion. I need a gamen, as we say in Anglo-Saxon England. So let us do something a little frivolous yet at the same time edifying and spiritually uplifting. Do not smirk! Below you will find five images from the marvellous Old English Illustrated Hexateuch, which was produced in Canterbury around the second quarter of the eleventh century. Each of them shows an emotion or a mood. You, blessed readers, have to work out which emotion or mood is represented. The key lies in the gestures each character is deploying. The gestures are drawn from the Roman stage. The scenes are all from the book of Genesis. Gamenaþ! 1 Starting with the easiest. What emotion is Hagar feeling on seeing this angel suddenly appear?  2 No longer in Eden, what emotion is Eve feeling?  3 Oh Lord! What is Abraham's mood after his wife's servant girl Hagar gives birth to his child?  4 Ignore the sheep! What feelings do these two brothers of Joseph have? (A third brother on the right feels the same.) 5 What is Abraham's mood before King Abimelech? Is it just me, or do the others have a balance problem? Now, you did enjoy that, didn't you? I know I did. Whoever gives the best answers will receive... well, I'll have to think about that.

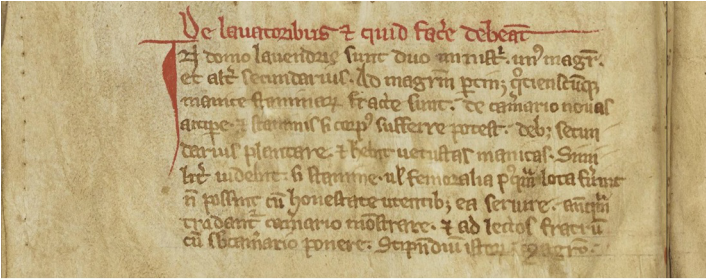

The Anglo-Saxon Monk lingers over the laundry duties of a medieval priory and discovers more than just soap and water Image: 'De lavatoribus et quid facere debeant', 'Concerning the launderers and what they must do', from Custumale Roffense, folio 59v (Rochester, late 13th-century). Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral. Blessed readers, I know many of you are of the opinion that medieval folk, even holy monks, were a smelly lot. No power-showers, no dry cleaning, and certainly no variable temperature selection with extra rinse option washing machines. I confess, I believe you're all slightly obsessed with washing in the twenty-first century, but I will pursue the matter no further. Rather, blessed ones, in order to disabuse you of your ill-formed prejudices, and to curb your tendency towards mental filth in general, I've provided below a short extract from the thirteenth-century Custumale Roffense, a customs book from the priory of Rochester Cathedral which includes a comprehensive description of the duties of the servants working for the Benedictine monks who lived there. Please note, if you do happen to be one of those rarely found readers with a delicate constitution, be advised that certain undergarments of the intimate variety are discussed in this text, and we will also be venturing beyond things which twenty-first century folk would associate directly with cleaning and washing. Yes, blood-letting! Image: Blood-letting, Luttrell Psalter, British Library 42130 (Lincoln, 2nd quarter of 14th century), folio 61r. Public Domain. Click on image to go to source.

|

Details

|