|

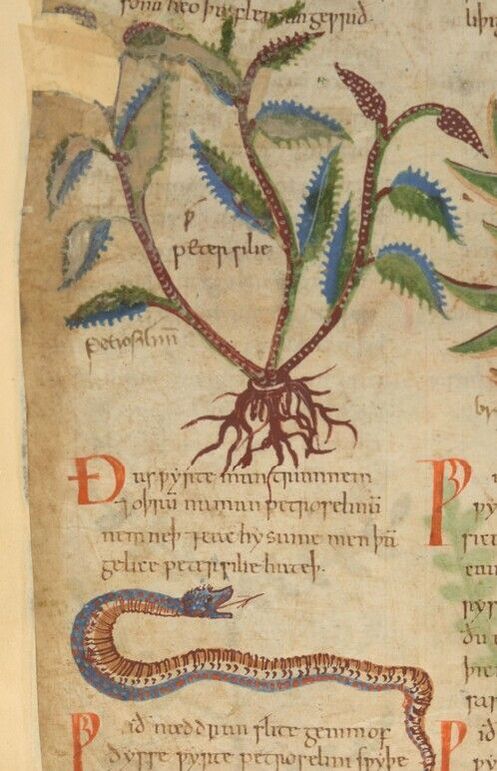

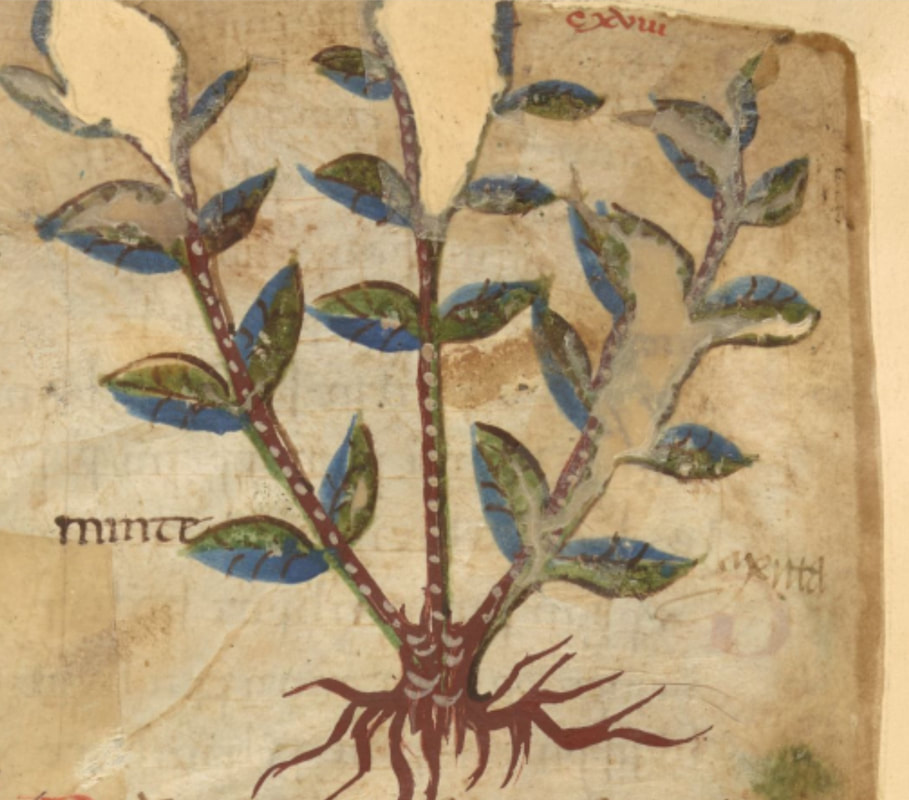

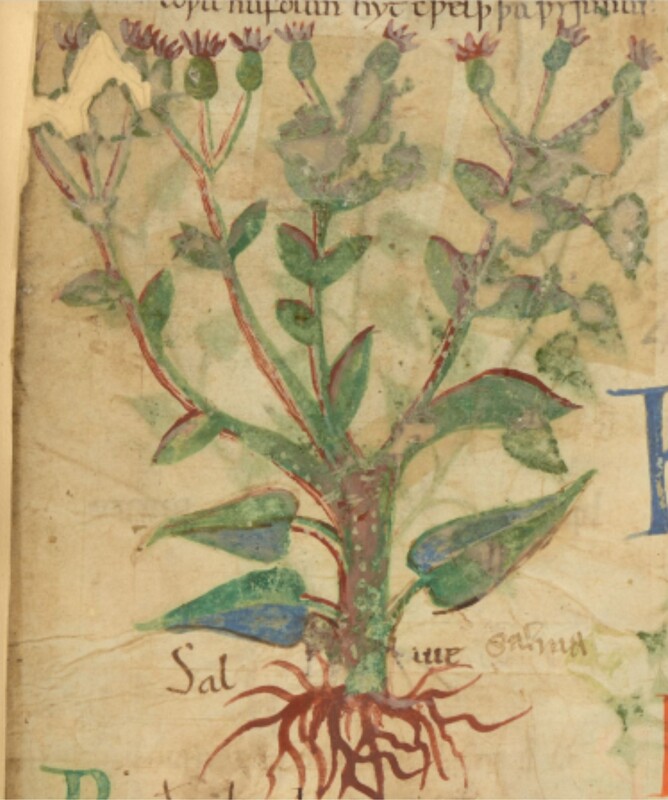

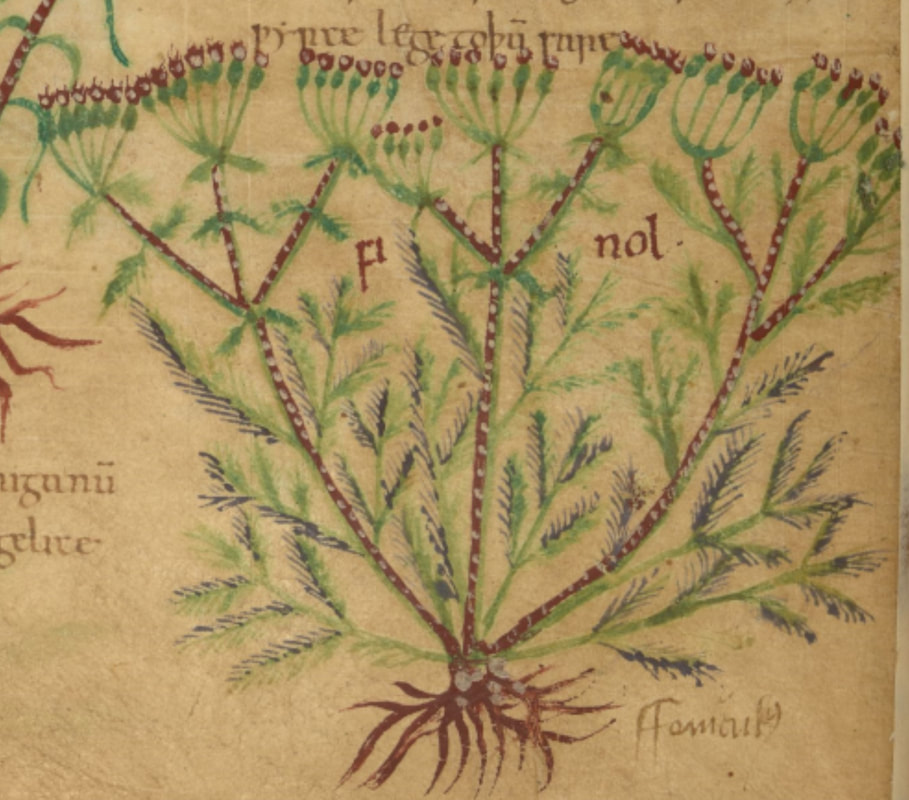

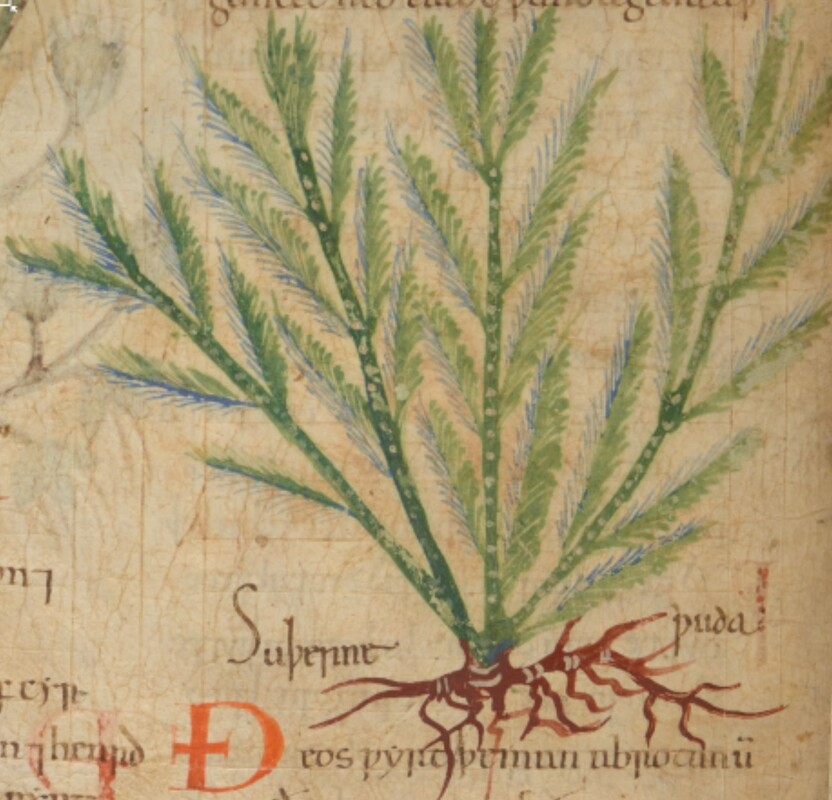

Blessed ones! It is so good to be back writing my blog. I'm quite sure you have missed my modest writings. Well, not that modest! Today, I want to provide a little extra insight into some research the other Monk of this website has been doing. Whilst Dr Monk continues cooking recipes from the fourteenth century, I thought it would be fun, if not vaguely spiritual, to take a closer look at some of the ingredients he's come across in Richard II's cookery book (Forme of Cury, c.1390), and tell you how we earlier English folk use them. So how about we take a gander at some herbs? Erbolate: a baked herby frittata Take persel, myntes, saueray & sauge, & tansay, ferbayne, clarry, rewe, dytayn, fenel, southrenwode, hewe hem & grynd hem smale, medle hem vp wiþ ayroun, do butter in a trape & do þe fars þerto, & bake hit and messe hit forth. The above quoted text contains the longest list of herbs in any of the recipes of the fourteenth-century Forme of Cury, written by King Richard's master cooks. Now, you may not know this, but the primary focus for herbs in my time, the turn of the eleventh century, is medicinal rather than culinary. Of course, herbs are still being used in medicine in King Richard's day. In fact, in the preamble to his cookery book, it does say that his physicians had given their approval for the recipes therein, no doubt because they contain amongst other things lots of healthy herbs. Here, I am going to tell you about some, though by no means all, of the specific medicinal uses of each of the herbs listed above. So, welcome to early English herbal lore! [See note 1] Parsley Parsley is named petresilige in the Old English (OE) text known today as Lacnunga, which means 'healings' or 'remedies' and is one of three major, early English medical works that have survived into your twenty-first century. The Lacnunga manuscript dates to about the year 1000. [2] The Lacnunga text has been described as ‘very humble work of non-specialist “folk medicine”’. [3] In this text, then, parsley is one of four main herbs that are combined with over 50 others to form ‘a holy salve’. The basis of this salve is butter, made ‘from a cow of a single colour’ – ‘all brown or white and unmarked’ – and a bowl of holy water. As the butter and holy water are being stirred and melted in a cauldron, various psalms and charms are to be sung. Then the concocter adds some of their own spittle to the mix and blows on it. Delightful! This is followed by a priest blessing all of the herbs, finely chopped, before they are, apparently, added to the mix. The priest’s godly orations over the herbs appear to address all the parts of the body for which the salve was suitable: basically, the whole body but with specific mention of head, eyes, nose, lips, tongue, underside of tongue, neck, chest, feet, and heels. [4] I don’t know about you, blessed ones, but I think I would rather eat King Richard’s herby frittata. MintsThere are various mints alluded to in OE medical texts, including wild mints – most likely corn mint (Mentha arvensis) and water mint (Mentha aqautica) – and the cultivated, garden variety, spearmint (Mentha viridis), known in OE as tunminte, ‘town’ mint. Mint, OE minte, is one of the plants identified in the Old English Herbarium. This work is a translation of a Latin compendium of texts written by various late-Antique authors; it survives in your century in four manuscripts, including a marvellous illustrated version dating to the first quarter of the eleventh century, and from which all the images in this post are taken. In this work, the juice of mint, pounded with sulphur and vinegar, is the go-to treatment for that age-old ailment, ‘ringworm’, [5] but it is also recommended if you have a ‘pimply body’ (your guess is as good as mine), and is to be smeared on with a feather. [6] How very sensual! Savory Sæþerie or saturege in OE, savory is an aromatic, hardy herb. It is mentioned in another early English work, or, more precisely, collection of works, known as Bald’s Leechbooks (a physician is known in my day as a leech, OE læce). Bald is named as the owner of the manuscript in which the Leechbooks are found, and the text was written down by a man called Cild. It is probably the oldest surviving complete medical work written in the vernacular, dating from about 925-950. [7] Leechbook I and II are ‘a collation of Mediterranean and English medical lore’, whereas Leechbook III, it has been argued, ‘most closely reflects early English medical practices’, before they were strongly influenced by Mediterranean medicine, something suggested by its use of English names for plants and materials, rather than Anglicised Latin ones. [8] In Leechbook III the seeds of savory are combined with numerous other plants’ seeds and pepper to make a ‘powder-drink’ (OE dustdrenc) as part of the treatment for ‘the yellow sickness which comes from oozing gall’ (perhaps referring to jaundice). A ‘good spoonful’ of the powder was added to a cupful of ‘strong, clear, ale’ and drunk at night. As well as the yellow sickness, this drink is presented as a bit of a cure-all, ‘good for every infirmity of the limbs’, as well as headache, insanity, earache, deafness, breast pain, lung disease, loin pain – and even ‘for each of the enemy’s [the devil’s] temptations’. [9] Perhaps, then, some of the less spiritually hardy of my readers might bare this concoction in mind. Just saying! Sage Now, I am going to whisper about the use of this next, well-known herb, because I realise that I have a few readers with delicate sensibilities, and, truthfully, I do not wish to put you off your herby frittata. Sage, OE saluie or salfie (derived from the Latin name, Salvia officinalis), is used in the Old English Herbarium. Let me just quote it in full: 1. For an itch of the genitals take this plant which [one] calls ‘sage’, boil in water and smear the genitals with the water. 2. Again for an itch of the bottom, take this same plant ‘salfian’, boil in water, and bathe the bottom with the water, it soothes the itch remarkably. [10] Let us move on. Tansy The leaves of tansy, known as helde in OE, [11] are used along with sage leaves, rue leaves, fennel leaves, and various other leaves to make a ‘good drink against every evil’ – never a bad thing to have at hand, I’d suggest. I rather like this drink, which appears in the Lacungna: you pound the leaves together and add them to wine or clear ale; then you strain the herbs off; and then you sweeten the drink with honey. It’s what we monks take if we’re needing to bleed ourselves. The Lacnunga does also say you can bathe yourself in front of a hot fire (which we monks do more often than you moderns think), and then let the drink ‘run onto every limb’, but I say that’s a waste of good ale! [12] Vervain Vervain, or herbene as we call it in OE, is one of the 50+ ingredients listed in the above mentioned ‘holy salve’. The other Monk informs me that in the twenty-first century, it should be avoided by anyone we know might be pregnant or breast-feeding, as it is potentially toxic. Now, why did he mention that to me? I am, after all, a holy monk! [13] Clary This herb, sometimes called clary sage by you modern folk, and known in OE as slarie or slarege, is mentioned just a couple of times in Lacnunga. In one remedy, clary seeds form part of a health drink, along with seeds of fennel, rue, two types of mint (‘garden’ and ‘horsemint’), sage, and far too many other plants to name – when do they think I’m going to find the time to pick and harvest all these cursed herbs and seeds? I do apologise. According to Lacnunga, a certain King Aristobulus – ‘wise and skilled in healing’ – had this concoction as ‘a good morning drink against all infirmities which stir up a man’s body’. Sorry women readers, this one’s not for you, it would seem. The text continues to enumerate a whole host of specific ailments it apparently cures, but my eye was caught by ‘the brain’s dizziness and agitation’ and ‘seeping cerebrum’. [14] Now, it just so happens I know someone with a leaky brain… “Dr Monk!” Rue Known as rude in OE (derived from Latin ruta: the plant is Ruta graveolens in full), rue is extensively used in both Lacnunga and the Herbarium. In the latter it is used to treat seven specified ailments, from a bleeding nose to stomach ache, from poor eyesight to headache. But my favourite use is by far this one: For the ailment which one calls ‘litargium’ that is called in our language ‘forgetfulness’, take this same plant ‘rutam’ soaked in vinegar, then sprinkle the face therewith. [15] I can most fervently recommend a quick sprinkle of rue and vinegar, especially to those of my readers who keep forgetting to read their daily psalms. Some of you might need a generous dousing of the stuff, but a light splattering of the face should suffice for most. Dittany (Dittander) Now, blessed ones, this herb is most awkward for me, a monk born in Mercia, to identify. This is because the ‘dittany’ of Richard’s baked frittata is most likely referring to what modern English folk call dittander, or sometimes pepperwort or peppergrass – in Latin, Lepidium latifolium. [16] Dittander, rather a scarce plant, generally grows along the edges of coastal saltmarshes and the damp grounds of South East England and East Anglia, many a mile from my birthland in the Midlands. [17] Dittander – the young leaves of which apparently have the taste of creamy horseradish sauce, [18] which the other Monk says is delicious with roasted beef – does not appear in the early English works discussed in this post.[19] My advice, then, is waive any weird potions or salves, and just this once follow Dr Monk’s implicit advice, and so tuck into some hearty fare with a joyous peppery condiment. Fennel Fennel, OE finol or finule (derived from the Latin name foeniculum vulgare), is widely used in my time, in both drinks and salves, some of which may prompt a raised eyebrow from one or two of you, my beloved readers. But incredulity be damned! Fennel appears in Leechbook III as the last ingredient in a salve, which is to be smeared over your face in order to protect you from ‘the elvish race, and nightgoers, and the people with whom the devil has intercourse’ – close your ears, blessed ones, close your tender ears! As well as fennel, you need twelve other plants, ranging from garlic to wormwood, some butter, sheep’s grease, ‘a lot of holy salt’, and an altar over which to sing nine masses – so you may well need your local priest, too, if he’s available. [20] So, blessed ones, no need for doubt or fear. Just smear! Smear, I say! Southernwood Suþernewudu in OE, and sometimes known as lad’s love in your timeline, is a bit of a let-down as my final herb – no protection from devilish fornicators or elvish folk for this one, alas! Still, if you tend towards the asthmatic, or are perhaps plagued by boils – or wens as we call them in my world – well, southernwood is what you need. Pounded together with various other plants, including such things as English turnip, fennel, and sage – oh, and ‘a good deal of garlic’ – all wrung through a cloth into clarified honey, allowed to steep before adding various spices, bark, and laurel berries, and then finally boiled down to double its strength, then, as Lacnunga says, ‘you have a good salve against wens and against asthma’. [21] And probably against your neighbours, family, and friends, too. Well, whoever said early English herbal lore was fun. Oh, that was me, wasn't it? May the Lord shower you with sweet herbal blessings! Notes [1] Information about the use of herbs in early medieval England is based on Stephen Pollington, Leechcraft: Early English Charms, Plant Lore, and Healing (Anglo-Saxon Books, 2000). Please be advised that some of the herbs mentioned in this blog post are potentially toxic, so this blog post is not advocating the consumption or medicinal use of such herbs. It is your responsibility to inform yourself of potential risks.

[2] See Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 196 (no. 63). Other Old English forms include petorsilie and petersilie: see, for example, Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 382 (no. 12) and p. 264 (no. CXXIX). All Old English forms derive from the Latin name for parsley, Petroselinum sativum; Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 145. [3] Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 72. [4] For the full text of the ‘holy salve’, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 196-99. [5] Pollington’s translation of OE teter. J. R. Clark Hall’s A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary offers ‘skin eruption, eczema, ringworm’. [6] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 338-39. [7] See Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 69. Pollilngton gives 950; the British Library gives 925-950: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/balds-leechbook. [8] Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 69; Pollington cites M. L. Cameron, Anglo-Saxon Medicine (Cambridge University Press, 1993), chapter 6. [9] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 382-83. [10] Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 333. [11] Pollington, Leechcraft, p. 158. [12] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 228-89. [13] On vervain's potential toxicity, see: https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-88/verbena. [14] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 236-37. [15] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 324-27. [16] See the commentary for ‘Dytawnder’ in ‘A Fifteenth Century Treatise on Gardening By “Mayster Ion Gardener.”, Archaeologia (1894), pp. 157-72, at p. 168, which identifies ‘Dittany’ with ‘Lepidium’, i.e. dittander. The alternative is that the ‘dittany’ of the Forme of Cury recipe refers to Dittany of Crete, Origanum dictamnus, but this seems unlikely to me since this is a very tender herb that grows in the wild only on the island of Crete. [17] More on dittander at: https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/wildflowers/dittander. [18] According to https://www.norfolkherbs.co.uk/product/dittander-lepidium-latifolium/. [19] Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 113 and 128-29, suggests possible links for ‘dittany’ to be ‘Hillwort’ and ‘Hindhealth’ but neither of these seem identifiable with dittander. [20] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 396-97. [21] For the full text, see Pollington, Leechcraft, pp. 188-89.

13 Comments

Hello readers, As you have likely noticed, I have changed the name of my website to The Medieval Monk. The reason for this is two-fold: First, a recent but ongoing debate within the scholarly community of medieval studies has shown that the term 'Anglo-Saxon' has a history of both racial and racist connections. Though in Britain, where I come from, 'Anglo-Saxon' is primarily perceived and used as a historical term to describe the people and culture of early medieval England (c.450-1066), in other countries, such as the USA, 'Anglo-Saxon' is synonymous with 'white' and has long been primarily understood as relating to race and, moreover, has been frequently misappropriated within racist discources. Since many of my readers are from the USA and elsewhere beyond Britain, I feel it's important for me to distance myself clearly from any racist misappropriation of 'Anglo-Saxon', and by far the easiest way to do this (though it costs both time and money) is to re-name my website and change my domain. The second reason I have for the name change is that it reflects better the recent shift in my research as an independent scholar and freelance consultant. Though I continue to write, research, and consult within the area of early medieval English culture (what is still called Anglo-Saxon Studies), I have significantly expanded into later medieval culture. For example, I'm currently writing a book about the fourteenth-century cookery book, Forme of Cury. So 'The Medieval Monk' better represents what I actually do (i.e. work across the whole medieval period), though I think it's important to remind you that I am still not a real monk! Thank you everyone for supporting this website and I hope to continue to produce relevant (and fun) information about medieval England and its peoples. Christopher Monk P.S. For anyone wishing to understand the various meanings and uses of 'Anglo-Saxon', I found this recent article very helpful:

|

Details

|