2 Comments

Patricia Bracewell is a great cure for the common cold. Not that my cold was some ordinary Man Flu. We’re talking Anglo-Saxon epic proportions here! Anyhow, this wonderful woman (she singlehandedly kept me sane at a dinner for Anglo-Saxonists in Kalamazoo!) has written a novel about the rather overlooked Queen Emma, a brilliant piece of storytelling that helped me cope with the most miserable day of my tissue-strewn sofa confinement. SHADOW ON THE CROWN: BETTER THAN LEMSIP!* *Theraflu (US readers) I want to start with a simple question: Why Queen Emma? Because someone had to tell her story, and I wanted it to be me. I first stumbled across a reference to Emma of Normandy about fifteen years ago. A posting on an internet bulletin board mentioned the barest details of her life: daughter of the duke of Normandy, wife to two kings of England, and mother of two English kings. I had considered myself fairly well versed in English queens, but despite my class at university on the History of England, my degrees in English Literature, and my wide reading of historical fiction, I’d never heard of Emma. I did some preliminary research, and the more I learned about this woman, the more astonished I was that she had been relegated to little more than a footnote in the history books. I wanted to write a book – well, three books, really – that would make her name just as familiar as those of the Tudor queens. A bit ambitious, I admit, but a worthy goal. How did you go about creating a believable Emma? What processes were involved? The process is virtually the same for every character that appears in the book. I have a long list of questions that I ask myself. The answers cover everything from physical appearance, to education, to ambitions, to friends and enemies, to what they’re afraid of, to sometimes lengthy descriptions of significant events that molded their personalities. All of that work takes place before I start writing, so I have pages and pages of material that never appears in the book. Of course, because I’m writing about people who actually existed, I also have to pay attention to what is known historically about the characters, and that has its own problems. For example, how old was Emma when she arrived in England? Historians speculate that she could have been as young as 12 or as old as 20, based on the – again speculative – birth years of her first and last offspring. I decided that a 12-year-old would be too much of a victim, and a 20-year-old too formidable for the kind of story I wanted to tell. So Emma is 15 when the book opens, and nearly 18 at its close. I suppose it’s no coincidence that I taught in a girls’ high school for a number of years, and that my students were in that precise age range. Emma, of course, marries King Æthelred – more popularly known as Ethelred ‘The Unready’. Now, I think it’s fair to say that you don’t appear to like him! How did you arrive at this rather haunted, mad, brutal king? He’s not exactly a charmer, is he? According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Æthelred came to the throne by way of his half-brother’s murder, an act that seems to have echoed down the ages. William of Malmesbury, writing in the 12th century, claimed that Æthelred was hounded by his brother’s ghost, and that was all the encouragement I needed to create the shadow that haunts the king. 19th century historian Edward Freeman brands Æthelred as “a bad man and a bad king”, although modern historians like Ann Williams have cut him some slack, claiming that he did his best to preserve his kingdom. Nevertheless, he certainly made some very bad decisions, and I had to come up with ways to explain them. Some readers have perceived the character I’ve created as mad, but I don’t see him that way. I see him as paranoid and guilt-ridden; a man who believes that God intervenes in human affairs and who is convinced that God has turned against him. Is such a man likely to be a warm-hearted husband and father? No. On the other hand, I tried to make him believable – not completely bad, either as a man or as a king. He is deeply flawed, though, and that makes him interesting to me as a writer and a reader. I really like the way we get to shift between the characters, to see life from their various perspectives. Was that what you wanted to do right from the beginning? It was indeed. I very much like the third person point of view, but the omniscient viewpoint was too distancing and too sweeping for the kind of story I was writing. I wanted to get very close to Emma, but at the same time I knew that there would have to be scenes where she could not be present. That meant that I would have to use someone else as my viewpoint character for those scenes. Æthelred was the obvious choice. But then I started to think about his relationships with his sons, and that brought Athelstan into the picture. And then I needed a foil for Emma, and suddenly Elgiva, who would play a role in Emma’s life much later on, was demanding to be heard. So I listened, and although I was warned that it was dangerous to have four viewpoint characters in one novel, I think it works. It gives a much broader perspective than I could have attained had I just stayed with a single viewpoint. I must confess that as an Anglo-Saxonist myself, I did a number of times reach for my Blackwell’s Encyclopaedia just to check some of your details. I was surprised, for instance, when you described an organ being played, I think in Winchester Cathedral. But, of course, you had done your research. Would you explain how difficult it is to avoid anachronism in historical fiction? And are you ever tempted to deliberately incorporate something anachronistic for the sake of the story? I’m glad that I passed your Blackwell’s test! I think it’s probably impossible to write a novel set in 11th century England that does not have anachronisms of one kind or another. I do not know what Æthelred’s bed chamber looked like, yet I describe it, spinning it out of my imagination probably based on other novels, films, and whatever else my brain conjures up, but certainly not on any documents that date back to the 11th century. How big was the great hall at Winchester or Headington? I don’t know. I can only base my description on the Heorot of Beowulf, on excavations of a 10th century manor at Cheddar, and on the size of halls that were built in stone two centuries later. The most difficult anachronisms to avoid are WORDS. Sometimes the precise word that describes a thought or an action is way too modern, and much as I tried to strike such words from my manuscript, a few slipped in despite my efforts. Just the other day I spotted orchestrate - meaning ‘to manipulate to achieve an end’, and I could not believe that I’d missed that one; but there it was, staring at me from the page. Mummery is a word that appears in Elgiva’s thoughts as she observes the royal family’s false display of unity. My editor and I agonized over it because mummers don’t appear until much later, so that concept would not have been around in the 11th century. In the end we decided to keep it because it was so apt a description and we couldn’t come up with something better. Writing this book has made me aware of just how rich the English language is, but it’s quite frustrating to have so much of it unavailable to me because of the time in which the book is set. At the same time, it was fun to introduce readers to Old English terms like burh, gafol, hird and godwebbe that I hope keep the reader grounded in Anglo-Saxon England. So. Sex. I think you deal brilliantly with sex. It’s very important to your plot and characterisation, especially when it comes to Emma. Obviously your scenes are fiction, but on the other hand you bring to life the magnitude of sex in the context of royal reproduction. But how would you respond to the accusation that you are stereotyping medieval sex as something rough and brutal? I would say that a reader should look beyond the relationship between Emma and Æthelred. Consider Emma’s brother and his wife Judith for example, or Hugh and Wymarc. Emma recognizes the tenderness expressed between these couples, and she observes bitterly that such intimacy has been denied her – not because of the age in which she lives, but because of the temperament of the man to whom she is bound. One of the things that I wanted to explore in the book was not so much medieval sex, but a particular, medieval, royal marriage. How would a 15-year-old girl negotiate the pitfalls of a marriage to a man twice her age – a man who weds her for policy, who mistrusts her and who is all-powerful? She is consecrated not just to the throne but to the king’s bed, and the expectation of church, state, court and family is that she will submit to his will. It could not have been easy, that role of peaceweaver between enemies. Yet royal daughters shouldered that burden for centuries. I don’t think that medieval sex and marriage were necessarily rough and brutal, but I think that the character of the Anglo-Saxon king as I’ve imagined him would be incapable of tenderness. Shadow on the Crown is the first of a trilogy. What’s next? And how long do we have to wait? The next novel in the series is titled THE PRICE OF BLOOD. It picks up Emma’s story in 1006, a year after the conclusion of the first book. All the characters from Shadow on the Crown return, and the canvas broadens to include London, Holderness, Sandwich, and several of the king’s manors in the Thames Valley. The Vikings give the English no respite, Elgiva and her family stir up more trouble, and Emma faces war, treachery and grief. The book will be released by Viking in February, 2015 in the U.S., and HarperCollins will release it in the UK in June. Thank you, Chris, for posing such terrific questions and for giving me an opportunity to discuss my book and the remarkable Queen Emma. Go on! Have your say! What do you think about historical novels set in the medieval world? Read any good ones you'd like to share? Or terrible ones?

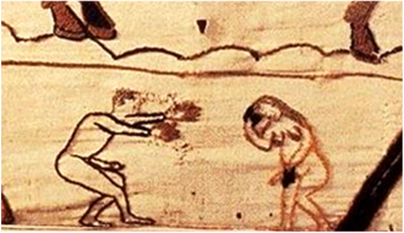

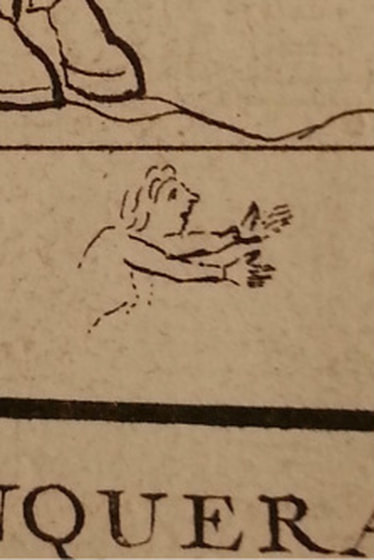

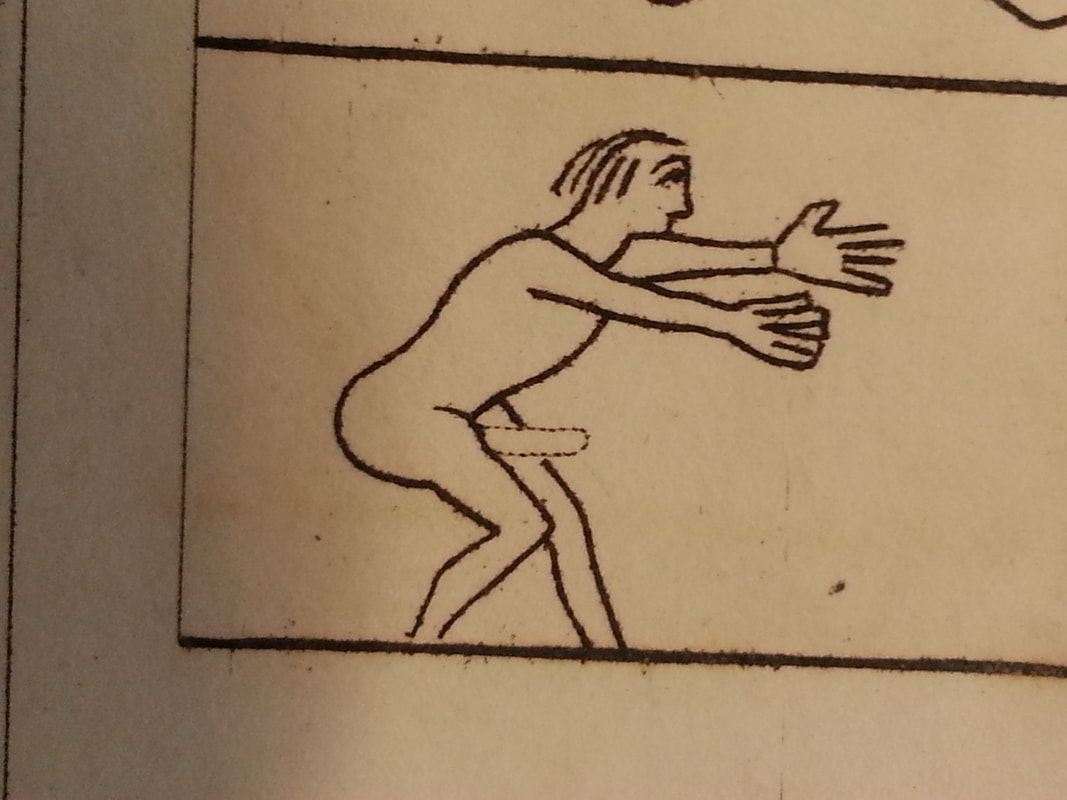

Whilst carrying out some research on the naked characters inhabiting the borders of the Bayeux Tapestry, I came across a wonderful, gendered tirade by a certain Miss Agnes Strickland, author of the 1853 work Lives of the Queens of England. Her gripe was against contemporary masculine interventions into the issue of restored figures in the famous eleventh-century embroidery. With quintessential, restrained Victorian ire, Strickland wrote: ‘With all due deference to the judgement of the lords of creation on all subjects connected with policy and science, we venture to think that our learned friends, the archæologists and antiquaries, would do well to devote their intellectual powers to more masculine objects of enquiry, and leave the question of the Bayeux tapestry (with all other matters allied to needle-craft) to the decision of the ladies to whose province it belongs. It is a matter of doubt to us whether one, out of many gentlemen who have disputed Mathilda’s claim to the work, if called upon to execute a copy of either of the figures on canvas, would know how to put in the first stitch’! Leaving aside what appears to be a misplaced defence of Queen Mathilda’s actual handiwork – no Bayeux Tapestry scholar, female or male, would today attribute even the commissioning of the Tapestry to the wife of William the Conqueror – I find myself rather moved by Strickland’s needled vehemence. After all, she has a serious point: don’t comment on things about which you don’t understand! I’m not agreeing per se with Strickland’s gender bias, but I do think it is relevant, when attempting to argue about meanings within the Tapestry, that we recognize the importance of practical knowledge of embroidery production. Which brings me back to my involvement with the Tapestry’s naked figures. I have to confess that in writing the initial draft of my chapter for a forthcoming collection of essays on the Bayeux Tapestry, I rather ignored the issue of post-medieval needlework restoration – or should I say I was actually ignorant of the extent of this in connection with the naked figures. You see, to get to the point, I have a naked man in the lower border – let’s call him Adam – who may or may not have an erection! He certainly has one now – rather serpentine, if truth be told. But in drawings of the Tapestry, commissioned by a certain Bernard de Montfaucon and published in 1730, the bottom half of the man is missing. Never mind a penis, Adam doesn’t even have legs! However, his active member is apparent in the later drawings by Charles Stothard, published between 1818 and 1823, though Stothard’s version of the man’s legs are not as they appear now on the Tapestry. You see my problem? There was no point in me waffling on in my chapter for this book about the metonymic significance of this man’s overt masculinity to the Bayeux Tapestry’s overall narrative (yawn) if there wasn’t an erection in the first place. So you see, with Strickland’s words ringing in my ears, I realised that I needed an expert in medieval embroidery. Luck would have it that my friend and former colleague at the University of Manchester, Alex Makin, is both an expertly trained embroiderer (Royal School of Needlework) and an expert researcher of medieval embroidery. (She is also contributing a chapter to the new book.) So I have put Adam’s problematic penis in her hands ... better rephrase that ... I have asked Alex for her professional opinion on the stitch work of the offending scene. In due course, we will hopefully all know, with a higher degree of certainty, whether or not Adam had an eleventh-century erection. So stay tuned. But, alas! If only Miss Agnes Strickland were still alive! I’m convinced she would have been delighted at my careful scholarship. If you'd like to have your say on this vitally important issue, please leave your comment below

Just a very quick post prompted by Carol W's response to my previous post. Carol pointed us to the Blemmye in the Hereford Mappa Mundi, and I just thought I'd let you all know about Hereford Cathedral's rather good interactive Mappa Mundi Exploration. Check out the colour enhancer. What does everyone think?

|

Details

|