|

In off the moors, down through the mist bands God-cursed Grendel came greedily loping. The bane of the race of men roamed forth, hunting for a prey in the high hall. (Beowulf, lines 710-713, translated by Seamus Heaney) The poet of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf certainly exploited the association of movement with the lurking terror of monsters. In the original language – Old English – the movement of Grendel is amplified by the pounding alliteration at work: ‘Grendel gongan, Godes yrre bær.’ And so we almost hear his doom-laden, monstrous strides. Cue ‘OMINOUS MUSIC’, or so goes the 1997 draft of the screenplay for Robert Zemeckis’ movie version of Beowulf. But I had better not annoy the purists with allusions to that CGI-enhanced visual paean to Angelina Jolie’s curves. (Though I can't promise not to let the occasional reference surface.)

2 Comments

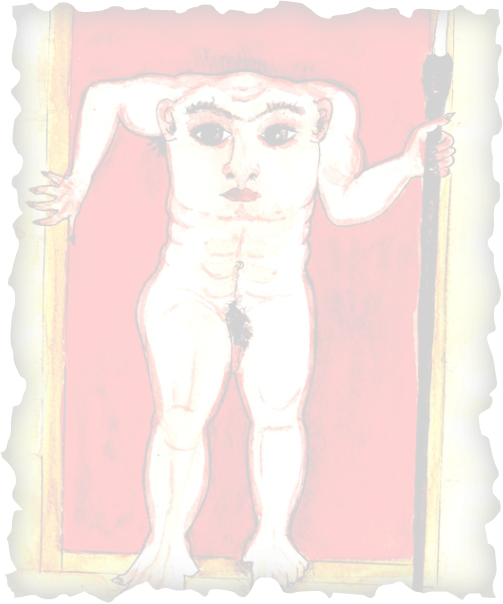

Just a quick post today. If you like riddles, you may also like Old English riddles. My friend Megan Cavell has a witty blog all about them. She's not your run of the mill academic (i.e. fusty, frustrated/frustrating, far away - some Anglo-Saxon alliteration there!), and so she manages to successfully combine her innate sense of fun with her in depth knowledge of this little known genre of medieval literature.  A Roman terracotta baby A Roman terracotta baby I went to a really good conference yesterday at the University of Manchester, 'Objects and Remembering'. There were some exceptional papers, including a very moving keynote by Dr Layla Renshaw. She discussed her work as a forensic archaeologist and anthropologist in the exhumation of mass graves from the Spanish Civil War. It was both fascinating and affecting to learn how those who were alive at the time of the atrocities, as well as the descendent of those who were massacred, consistently constructed their memories of the dead via physical objects. These were not only things that had been physically exhumed along with the bones of the deceased – spectacles, a buckle, pencils, a ring – but also objects raised up from people's memories, things long gone, and visible only to the mind and heart. One individual recalled the corduroy suit one of the victims had worn on the day he was taken to his death, The suit, perhaps memorable as something rather fashionable at the time, was thus the link to the past, an object that somehow uniquely represented a loved one – and perhaps in a sense represented the loss of that one too. Layla’s book on her study of these exhumations is now for me a must read. To something at the other end of the life-death spectrum, and to a few thoughts triggered by another of the really interesting papers at the conference, one by the first speaker, Dr Emma-Jayne Graham of the Open University, who was looking at Roman votive objects in the form of terracotta babies. Hundreds of these astonishing objects have survived. They are typically life-sized, and all of them are represented as swaddled. Emma-Jayne explained how they were probably given by parents as offerings to gods in recognition of real babies passing into the next stage of human life, of the moment when they could be released from the protection of swaddling – a rite of passage, in other words. I asked her about the faces of these babies, whether they were realistic. She said some were, but others looked like old people, and others like aliens! A fair description of all babies, I thought. Anyway, inevitably, my medieval brain made an association with Anglo-Saxon depictions of swaddled babies. In the manuscript known as Junius 11 (c. 960-c. 980), there’s a picture of Eve lying in bed holding up a rather static-looking, and rather big, baby (Cain), who then appears to float over towards Adam. (The link to it is HERE, though you need to zoom in to see it properly.) In another manuscript, the Old English Illustrated Hexateuch (c.1020-c.1040), we have a series of what are called cenningtid or post-birthing scenes: mothers tightly wrapped in their bedclothes looking on at midwives attending to their babies. (You can see the cenningtid of Hagar on folio 28r; of Lot's daughters on folio 34r; of Sarah, folio 35r; and of Tamar, folio 57r HERE. The images are copyrighted so I can only provide you a link to them. Unfortunately the slightly clunky British Library manuscript viewer does not allow me to give a direct link to each one, only to the first folio of the manuscript, but you can easily navigate to the relevant folios via the drop-down box on the right of the screen. Again, you will need to zoom in for clarity.) I remember the first time I came across one of these images, in my early days as a PhD student. For a moment, I had thought the child was inside a cauldron! A baby being boiled in a cooking pot! Horrible Anglo-Saxons! Then, of course, I (fairly) swiftly reigned in my wayward imagination and realised it was a biblical birth scene. As you can see, the babies are again depicted scarily big – no nod to realism here. One other thing of interest for me is the fact that the midwives in these scenes are always shown with uncovered heads, as opposed to the mothers who are shown formally with typical head-coverings. I find this detail rather touching in an odd sort of way: as if we’re being invited into the more private side of begetting offspring. And if you find this hint of intimacy curious, then you will want to know that the only other instances in this manuscript where women are shown with uncovered heads are in scenes depicting sex. But that’s for another time. 18/6/2014 Sex in early medieval penitentials: confession, the power of the mind - and nuns' toys!Read Now Early medieval penitentials were handbooks for confession used by priests. They provided a 'tariff' system for confessors to help them determine how much penance -- usually in the form of fasting -- should be handed out for a particular sin. Sexual sins are prominent in extant penitentials, and it is surprising how explicit the details are. At times, some of the guidelines to the priest are almost excruciating in their attention to sexual minutiae. For example, in one Old English penitential, there is a penance applied for someone who uses the power of his mind to create an orgasm! I believe we can learn a great deal about medieval attitudes to sex, and about the range of sexual practices in the early medieval period, if we take the penitentials as serious historical evidence. What we have to realise is that these works don't simply represent an obsessional or even lurid taxonomy of sin, but rather they signify what Allen Frantzen has described as an intersection of text and the actual practice of confession. In other words, they are a distillation of the real-life experiences of countless people confessing, or being urged to confess, intimate details about their lives. The penitentials are, in effect, a recorded performance or narrative of everyday medieval people. One final point about the penitentials -- and I apologize for my weakness for salacious detail -- but it is rather amazing that one Latin penitential actually refers to nuns using a machina in fornicating -- which seems to suggest the use of dildos! Remarkable! |

Details

|