|

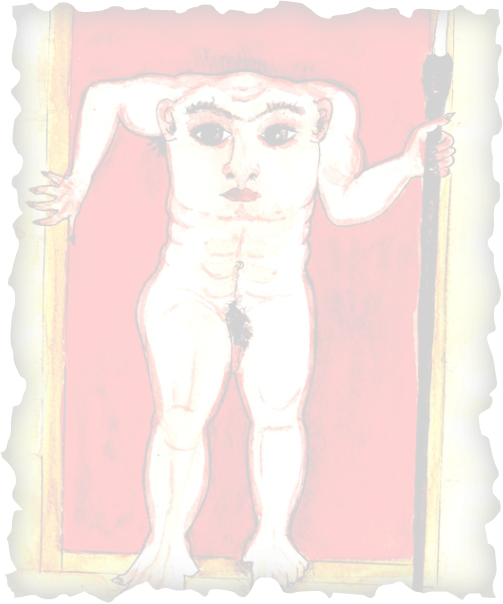

In off the moors, down through the mist bands God-cursed Grendel came greedily loping. The bane of the race of men roamed forth, hunting for a prey in the high hall. (Beowulf, lines 710-713, translated by Seamus Heaney) The poet of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf certainly exploited the association of movement with the lurking terror of monsters. In the original language – Old English – the movement of Grendel is amplified by the pounding alliteration at work: ‘Grendel gongan, Godes yrre bær.’ And so we almost hear his doom-laden, monstrous strides. Cue ‘OMINOUS MUSIC’, or so goes the 1997 draft of the screenplay for Robert Zemeckis’ movie version of Beowulf. But I had better not annoy the purists with allusions to that CGI-enhanced visual paean to Angelina Jolie’s curves. (Though I can't promise not to let the occasional reference surface.) It’s fascinating that the movement of monsters is also sometimes exploited to great effect in the art of the Anglo-Saxons, which is quite surprising on one level, as their manuscript art is sometimes perceived as quite static. In the example I'm thinking of, we don't actually see any of Heaney's greedy loping, but we do witness something perhaps equally as perturbing: a monster who's about to launch itself off the page! Say hello to the Blemmye! This headless (acephalous, if you want the technical term) creature, with its face fused to its chest, is one of the so-called Wonders of the East. (I hope you like my rendition of it at the top of he post!) In an eleventh-century English manuscript, this seemingly male Blemmye stands, fully naked, on the edge of the frame. His big black unblinking eyes stare at you, assessing you. You just have to stare back. After all, he's not so terrifying. He's not quite in the Grendel mould, well not the Grendel Ray Winston faces, who thrashes and smashes warriors like little rag dolls. (Sorry, couldn't resist.) Perhaps, though, like Grendel he is hungry for flesh, for his ribs are poking through his skin, just under his jowls. No doubt, you notice his six toes. The ones at the back, which resemble dewclaws of a dog, seem to grip the bottom of the frame, whilst his surprisingly elegant fingers curl around the sides. It would seem this Blemmye is set to leave behind the bare rocks and troubling, fiery sky of his own world. Will he step off the page? Will he launch himself into your world? What seemed to disturb the Anglo-Saxons about these types of monsters – the monstrous races, as they’re sometimes called – is their familiarity. They are not fully human, but even in their deformed otherness there’s enough about them that speaks of human origins. Indeed, the prevailing theological view of the early medieval period was that monsters originated from Cain, the firstborn son of Adam and Eve. The Beowulf poet picks up on this: Grendel and his mother (she's left unnamed) are said to be from the kin of Cain, and they are said to have lived for a while in the home of the monster race. Perhaps, then, for those Anglo-Saxons who imagined these monsters, whether in dreams or when wide awake, the peril of their proximity was disturbing in the first place because, like all people, they shared a genealogy with monsters! Update from the Anglo-Saxon Monk (June 2017)

Dr Monk tells me he still has a number of print-offs of his article linked above. If you live in the UK, he'd be happy to send you a free copy (postage paid), whilst stocks last. Sorry readers outside the UK, his sceattas only stretch so far. To request a copy, use the Contact Me page. And don't forget to leave your address!

2 Comments

CarolW

27/6/2014 11:32:41 am

To my poultry-rearing mind - the Anglo-Saxon Blemmye displays feet remarkably like a cross between a human and a bird - the toe/claw at the back helps to grip the branch / frame - in much the same way as the regal bird of prey grips the arm of the thane. He's much more bodily muscular than the Blemmae of the Hereford Mappa Mundi - whose feet are most definitely human - in shape and toe count. The Mundi Blemmae is a monster contained and bounded within the frame, both geographically and artistically, with a physicality rather 'limp' and is far less threatening than the Anglo-Saxon version above. A/S pictorial representations often appear to be stepping over or out of the frame - are the monstrous perils intimidating physically, culturally and theologically the viewer's 'comfort zone'?

Reply

Chris, The Anglo-Saxon Monk

4/7/2014 02:50:47 am

Thanks Carol for your observations. Our Anglo-Saxon Blemmye seems then to have an extra bit of hybridity with those feet!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|