|

31/12/2014 Medieval oaths: 5 things you should know before making those New Year's resolutionsRead NowWhether you're contemplating making a resolution, vow, promise, pledge, or even a sworn oath, the New Year awaits, and it's time to gird up your loins! With great vigour and vim, the Anglo-Saxon Monk tackles the fascinating subject of oath-making in early medieval England. After a week of frivolity and feasting, you, my blessed readers, may now be feeling just a tinge of guilt as well as a wave of melancholy bordering on moroseness. Somehow, though, urged on by that internal (and infernal) cycle of life, you may suddenly feel that you’re about to bolster your mind, stiffen your resolve and, indeed, gird up your loins.

Promises to renew with verve your visits to the blessed gymnasium and even to forfeit mead for a month will follow, no doubt. But, beloved beholders of blogs, I feel obliged to ask you, as you clear away your emptied cups of mirth, if you truly know the value of an oath. Why do I ask? Well, in the medieval world, oaths were taken most seriously. They certainly were not reserved for dubious, after-the-party declarations of good intentions. So to help everyone appreciate the importance of vows and oaths, I’ve decided to take a look at five fascinating facts about oath-making in early medieval England. Now, I will just say that I can’t promise you that my medieval morsels will be at all relevant to your current post-pleasure predicament, though I will do my best to identify a few parallels here and there. You deserve nothing less.

0 Comments

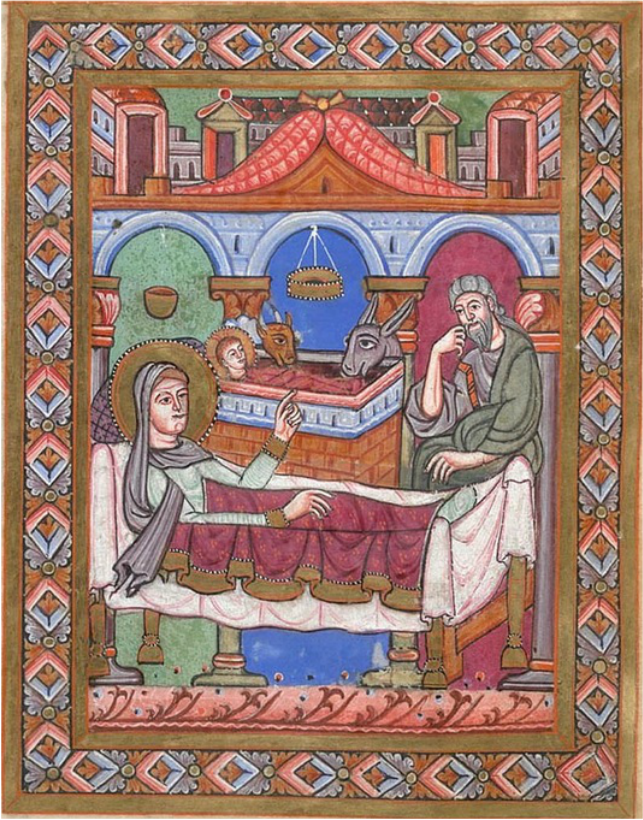

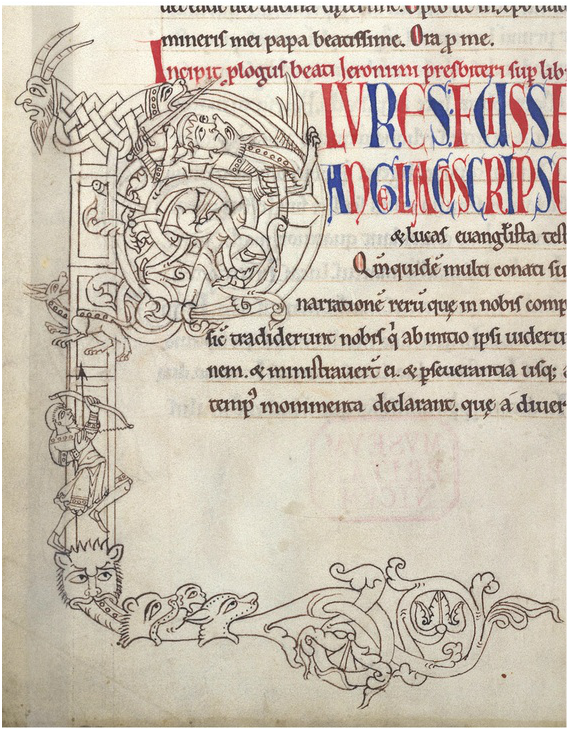

To say thank you to all of his blessed readers, the Anglo-Saxon Monk has picked three of his favourite Christmas scenes from the British Library's collection of illuminated manuscripts. And he's even thrown in a few words of monastic commentary for your delectation. What a generous soul! What's a Christmas Nativity scene without a donkey? This lovely example from Swabia, South Germany, has it all doesn't it? The rather splendid twelfth-century columns and arches of the humble stable, the generously bedecked, wooden bed for the Virgin Mary (nice pillow), and even the "I'm perplexed" gesture of Joseph. (Is he, I wonder, still finding it difficult to believe the Archangel Gabriel's story?) I must confess that I'm a bit concerned that the face of the Christ Child seems to be aged about fifteen, but that's just my personal opinion. And I suppose you've noticed that Donkey, and his friend Cow, do look like they're nibbling the Christ Child's blanket, and so not simply engaging in a bit of anthropomorphised adoration. "Naughty Donkey!" says the Virgin, wagging her finger at him. This is exquisite isn't it? As long as you don't mind those long faces! The enlarged detail is an historiated initial 'H', which forms the word 'Hodie' (Latin, 'Today') along with the text to the side. Thus it marks the beginning of the choir response for morning prayers (lauds) on Christmas Day. It is amazing how much detail has been packed into a painting that measures only about 40x40mm (not even 2x2 inches, my blessed US readers). Like the Swabian Nativity scene, above, the Virgin Mary has a rather lovely pillow (note the floral bobbles on its corners), and it also has those familiar stable animals, Donkey and Cow, complete with delicately painted muzzles, no doubt to stop any blanket nibbling. I can't help wishing the artist had taken the trouble to make Mary and Joseph look just a little bit cheerier. I'd even go as far as to say that she/he made Mary look a tad disappointed. But at least Joseph is acknowledging the swaddled Christ Child on high (a very high manger, wouldn't you say?). So come on, Blessed Virgin, radiate some heavenly joy, for you've just given birth to the Saviour of Mankind! OK, you sharped-eyed art historians! This is not the Nativity. But it is Christmas. In fact, it's a depiction of King Edmund I of East Anglia (r. 855-869), surrounded by his blessed bishops and other clerics at his coronation on Christmas Day. Talk about making an impact or, should we say, basking in someone else's heavenly glory?

But we will ignore the possibility of the latter by reminding ourselves that this most saintly of Anglo-Saxon kings was a bit unfortunate, for in the year 869 he was martyred by those terribly nasty, heathen Vikings! Never mind, he had a lovely Christmas Day in 855. Just look at the splendour! OK, it's true that we don't really know he was crowned on Christmas Day (it's a later medieval invention probably), but nothing will take away my joy at those amazing cloaks that the two bishops in the foreground are wearing. They are just so Christmassy! I would kill an Anglo-Saxon king for one like them. But not to be. For I am just the humble Anglo-Saxon Monk. A blessed Merry Christmas to you all! In 2015, the Anglo-Saxon Monk will be creating his ASMDirectory, a vehicle for finding medieval goodies and services. If you want to know more, click the link below:

I know you're all busy grinding your almonds and preparing your stuffing, but spare a few thoughts for the Anglo-Saxon Monk. He still has 7 days of fasting to do. Will he make it? So my trial by fasting continues. I don't have a nice horse like St Cuthbert had (see image above) to find me some bread and cheese wrapped in linen.

If you’ve been keeping up with my communications – and pray tell me why you wouldn’t want to hear about this most edifying of subjects – then you will know that I’ve been trying to get back on the pre-Yule-tide-fasting wagon by imagining that I’ve committed sins that require fasting for penance. Nothing too serious, blessed readers; I only need a few days more fasting to make it forty in total. So I went with gluttony-induced vomiting (7 days fasting) and then stealing carrion (another 7 days fasting), but although I left out imagining the eating part of the latter sin, I finally realised that I was acting contrary to the spirit of fasting. It was no good, I admitted, imagining food-related sins in order to inspire me towards greater efforts at fasting. Counterproductive, you might say. Now, with my scriftboc (penance book) in hand, and with just a week to go before I can feast, I’ve turned my attention to other minor sins that attract a few days of fasting. So, here are my final choices: First: ‘A priest who soils himself through impure speech or through the sight of or contemplation of a woman, but who wishes not to sin further, should nevertheless fast for twenty days.’ (Scriftboc, my own translation/ paraphrase.) This one’s a bit problematic. First, I’m not a priest, but rather a monk, though I’m sure the principle of this canon still holds true for me. Nevertheless, I don’t need twenty days of fasting, just seven. Perhaps if I were to just go with the impure speech part, and forgo the leering (I hardly see any women anyway, so they’re a bit difficult for me to conjure up), then I only need about a third of the 20 days. That might do. Next option: ‘A priest, if he is polluted by the desire of his thoughts, he should fast a week.’ (Scriftboc, my own translation.) This is more like it. OK, it’s the priest again (far more sinful than monks, I can assure you), but it has the advantage of not needing a woman. Just a bit of desire in my thoughts, that’s all. I can manage that. Finally, here’s one for five days. Perhaps I could imagine this and let myself off from the last two days of fasting: ‘A little boy, if he is pressed into sex by a bigger boy, five nights (of fasting); if he consents, fifteen nights.’ (Scrifboc, my own translation.) Well, the least said about that one, the better! But I have to say, what was the author of this penitential thinking? Penance for being a victim? Very unsavoury. And that’s put me right off my fasting all together. Surely there’s a way out of this agony! Aha! At last: ‘And he who must fast one week on bread and water, let him sing 300 psalms kneeling or 320 without genuflecting’. (The Old English Introduction, translated by Allen J. Frantzen.) Is this an alternative? It must be. And I can do that, I can do that! I don’t even mind the genuflecting. Ah, but even better: ‘And he who neither knows the psalms nor is able to fast, every day let him give one penny or its equivalent to needy people.’ (The Old English Introduction, translated by Allen J. Frantzen.) This one has to be for me. Really, it does. My brain has become so addled by the lack of food, that I think I may have forgotten half my psalter, and I really am not capable of forgoing food any longer. So I must break into my purse (never mind that I shouldn’t have one: vow of poverty and all that) and deliver my seven pennies to the needy. There must be some takers! Anyone? Go on ... you know you want to have your say, so please leave a comment below. So someone else is having a bash at doing Beowulf, that greatest of English epics! Well, something like it. Or, perhaps, a bit like it. Or, most probably, nothing like it. The Anglo-Saxon Monk asks if it really matters if we don’t get to see the real Beowulf ... I knew instinctively, as soon as I read ‘13-part drama’ in the Telegraph’s headline, that die-hard literary purists would be professionally disgruntled with ITV’s fit-for-the-Game-of-Thrones-generation version of Beowulf, our greatest Old English poem.

Now, there may be more than 3,000 lines of verse to play with, but thirteen episodes (presumably 13 x 1 hour, give or take an advert or six)! There has to be just a touch of scribal elaboration there, a hint of amplification. But shouldn’t we be happy that this beloved poem, written down into a manuscript a millennium ago, is still inspiring people in the twenty-first century? Overall, even as an Anglo-Saxon monk, I think we should. We might stamp our hose-and-leather clad feet and protest loudly that the Beowulf story doesn’t need ‘a new female Thane’ (the hero Beowulf’s apparent love interest, so clearly absent in the poem) and ‘thrilling chases’ (on ox-drawn wagons, no doubt) to make sense. Well, of course it doesn’t. I would go as far as to say that present-day audiences would actually get the themes of loyalty, vengeance and futility that surface from the poem’s complex storytelling; that they could be spared the hackneyed, Hollywood, heterosexist romance, just for once, without falling into confusion and despair. (I hope you liked my Anglo-Saxon inspired alliteration just then!) But stories change, don’t they? People are creative, aren’t they? They want to make things ‘relevant’ for today. The latest Beowulf may or may not be yours or my relevant, but it is someone’s, perhaps many persons’, idea of a meaningful story and/or great entertainment. Moreover, specifically with regard to the poem we now call Beowulf, who’s to know how it started out before it was actually put into the form in which it survives today? We know that medieval writers liked to adapt material, give something a different flavour, even, for example, when they were meant to be translating something sacred from Latin into the vernacular. So why shouldn’t today’s writers adapt Beowulf? Furthermore, it’s generally accepted that the poetry of Anglo-Saxon England evolved from an oral story-telling culture. Indeed, Beowulf itself plays with this very idea with its opening line, ‘Hwæt! We have heard ...’, and maintains the conceit of orality with its image of a scop (a singing poet) recounting famed stories of old. If the core heroic ideals and narrative of Beowulf originated and developed within an oral tradition, before the advent of a literary culture, then wouldn’t it be safe to say that the poem’s story was likely added to over the centuries? Shouldn’t today’s writers have a go at adapting it too? It’s interesting that scholars within Anglo-Saxon studies have argued for decades about the date of the poem – when it was originally composed, that is, not when it was written down in the Beowulf manuscript – and I think we should take something from that. Namely, that we can be pretty sure, based on the aforesaid medieval creativity, that the surviving Beowulf story emerged rather than arrived fully formed, that details shifted, new bits were added, old bits were taken away. Now, I’m adamant that there were no female thanes ever, and I’m almost as confident that Beowulf wasn’t especially intended as a story about, to quote ITV’s publicity material, a ‘mighty and capable man slowly reconnect[ing] with the notion of family and home’. It’s about beating up monsters and homosocial bonding, don’t you know! But, nevertheless, I think I will give it a try. And if some ITV agent is reading this, why haven’t you been in touch? Don’t you know I’m from the eleventh-century? Go on ... you know you want to have your say, so please leave a comment below. |

Details

|