12 Comments

No, I haven't decided to give up completely my normal mode of transport ... (donkey/cart) This train is the @communitytrain at North Manchester Radio FM 106.6. Please note: FM 106.6 (@normanfm1066). Those bloody Normans get everywhere! I'm being interviewed by Hannah Kate, local poet, publisher, mystery games designer, teacher, entrepreneur, academic, and ... well, she just about does everything. I'm on air between 14:00-16:00 (UK). UPDATE: You can now listen to the interview online, in two parts: First hour and Second hour. You may just want to fast-forward through the twentieth-century musical interludes ... and I was told we'd have some Anglo-Saxon organ music!

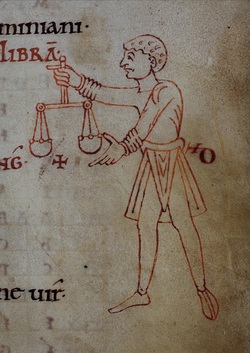

Apparently, I have competition. From tenth-century German nuns, no less. Well, more precisely, from a really interesting website by Sarah Greer, whose specialist interest is female monasteries, particularly early medieval ones in Germany. Her posts are really worth a read, and she tells me she has a new post due soon ... I'd better watch out.

|

Details

|