Growing up as a kid in the 1970s, I remember reading in my copy of Your Youth (published by the Jehovah’s Witnesses) that 90% of boys masturbated, whilst only 50% of girls did so. It made me think at the time that boys were somehow ‘dirtier’ than girls, and inevitably prone to sexual sin!

So when a few years ago I came across the writing of the Benedictine monk and school-master Ælfric Bata (great name), I was somewhat surprised to see that this perception of boys had actually been spoken about a thousand years ago. Bata’s Colloquies, or ‘conversations’, were compiled into a schoolbook designed to teach young students the art of communicating in Latin. But they turn out to be much more than that. Though clearly not documented ‘real life’ – they in fact read like dramatic spoofs – I would argue, nevertheless, that these conversations reveal Bata’s observations on the sexual dynamics in the all-male environment of Anglo-Saxon monasteries. The strict code of purity and temperance, propounded tirelessly by Bata’s own tutor, the rather grave Ælfric of Eynsham, is often a target of jest in Bata’s skits. Both students and masters are seen to constantly flout the regulations set out in the Benedictine rules for monks, known as the Regularis Concordia. Though the skits do not attack monastic principles per se, there is much within that may be read as mocking the performance of those whose duty it was to live the spiritual life. In the final conversation (Colloquy 29), however, a strict and moralizing tone is suddenly adopted. The Father exhorts his spiritual sons to a chaste and upright life, and is heard opining the naughtiness of boys: "For that reason I’ve written and arranged these speeches in my own way for you young men, knowing that boys speaking to one another in their way more often say words that are playful than honorable or wise, because their age always draws them to foolish speech, frequent joking, and naughty chattering." Earlier, the master had acknowledged the educational value of mixing ‘jokes’ with ‘wise words and sayings’, but here he asserts that boys have a tendency by themselves towards unseemly chatter. This propensity for indecent speech may have been perceived by Bata as just one facet of a typically boyish predisposition towards sexual naughtiness, something provocatively suggested in two of the preceding conversations. In Colloquy 25, a conversation full of outrageous scatological insults (master and student basically end up calling each other a piece of shit), the student is derided by the master as a ‘fox cub’, a ‘fox tail’, and ‘a little fox, the seed of a demon’! He is accused of ‘flattering and seducing’ the other boys, ‘leading them into bad behavior and deceitfully inviting them toward twisted deeds’. As the editor of Bata’s text points out, in medieval medicine the fox’s tail was seen as providing a stimulus for sexual intercourse. Its use as an epithet for the boy implies that his seducing of other boys towards twisted deeds was at least partly sexual in nature; and this is further underscored by the master’s sexualizing designation of the boy as 'semen demonis', literally, a demon’s semen. The sexual waywardness of male youth is also insinuated in Colloquy 9, where the bawdy euphemism of the ‘little brother’ with ‘beautifully long and curly hair’ betrays his predilection for sexual depravity. First, the boy is urged by his master to acquiesce to a fellow brother’s wish to be accompanied to the toilet. The boy is admonished to take care of ‘everything for him in the latrine’, prepare him for bed, and to ‘obey him in every way’. These activities clearly flouted the monastic rules: a monk taking a young boy alone ‘for any private purpose’ was strictly forbidden. It is this particular contravention, with its strong sexual overtones, that serves as the backdrop for the boy’s intoxicated speech once he returns from his errands and is rewarded with alcohol: “I want to drink from the horn. I ought to have the horn, to hold the horn. I’m called horn! Horn is my name! I want to live with the horn, to lie with the horn and sleep, to sail, ride, walk, work and play with the horn. All my kith and kin had horns and drank. And I want to die with the horn! Let them have the horn, those who are filling it and are about to give it to me! Now I have the horn. I’m drinking from the horn. Have every good thing, and let’s all be happy and drink from the horn!" One might insist on reading this passage as referring to nothing more than the boy’s desire to be constantly availed of a drinking horn (and, of course, it’s clear that this passage would have been a brilliant lesson for verb conjugation and noun declensions, zzzzzzzzzz), but it is not difficult to appreciate its sexual innuendo. And we can look to none other than the great Saint Isidore of Seville for support in this. In his seventh-century Etymologiae, a well-known encyclopaedia in Anglo-Saxon England, Isidore observes the licentious, bacchanalian significance of the horn. He notes that Liber (another name for Bacchus) holds both a horn and a vine garland ‘because when wine is drunk willingly and in measure it brings happiness’; and, pertinently, that through Liber ‘men are freed by sex through his agency when their sperm is released’. This association of the horn with inebriated, ejaculative sex led one scholar, David Clark, to conclude that Bata’s choice of horn ‘playfully associates the drinking of alcohol with oral sex’. I would suggest that the boy’s declaration of his various intentions towards the horn may well infer a rather larger range of inter-male activities! When I think back to my own sexual education, such as it was, I wonder now if the masturbation statistics cited were really accurate, or did their inclusion in my Youth book simply reflect a long held notion that boys are just naughtier than girls. As I hope I’ve made clear, Bata’s words certainly suggest that this notion has been around for some time. Now, before I get back to my solitary monkish musings, I have just one more thing to say about Bata and his book. In a final admonishment directed to his schoolboys, he urges them to ‘desist forthwith from all vulgar songs and allurements’. Master Bata! Isn't that simply a case of closing the stable door after the horse has bolted! (I couldn't think of a more obvious euphemism, apologies.) I think we are going to have to conclude that Ælfric Bata was a bit of a dodgy schoolmaster, with a bit of a dodgy past. For despite his Johnny-cum-lately protestations, he didn’t hesitate in the first place to include in a schoolbook a skit with an especially vulgar paean to the male member – uttered, of course, by a naughty boy.

6 Comments

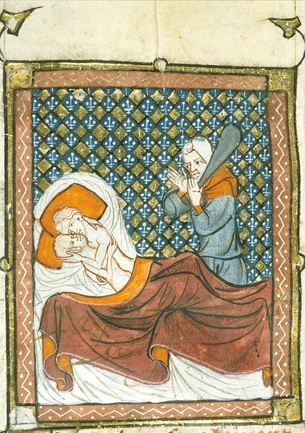

Roman de la Rose, British Library, Egerton 881 (France, possibly Paris, c.1380), folio 141v, detail: Vulcan finds his wife Venus in bed with Mars. Roman de la Rose, British Library, Egerton 881 (France, possibly Paris, c.1380), folio 141v, detail: Vulcan finds his wife Venus in bed with Mars. A couple of weeks ago I asked all you young lovers if you fancied an Anglo-Saxon betrothal ceremony, instead of the more run-of-the-mill engagement stuff. Well, I've found a little something to add to it: a pontifical blessing of your bed! Ever the romantic, me, I've dug out a mid-tenth-century Anglo-Saxon pontifical (the 'Egbert Pontifical' to be precise), and herewith present you all with its rather sweet words, which by the way are to be uttered by an appropriately sober priest (Anglo-Saxon priests may well have been defrocked for lack of sobriety). Oh, but before I present you with my translation (yes, I had to use my rather dodgy Latin skills to produce this for you), I must explain the accompanying picture. I know it's a tad saucy, especially if you read its caption, but I just wanted to reassure you that you do not need to follow its example by being in the bed when the priest (or whoever you've asked to oblige you) pronounces the blessing. And so as not to mislead you, the man on the right is not a priest. Why would a priest be holding a big club with which to hit you, come on now! The Betrothal Blessing: "God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, bless these young people of yours and sow the seed of eternal life in their minds, in order that whatever for usefulness they consent to, this they may desire to do. Through Jesus Christ, the assessor of men, who is with thee and with thy spirit, bless, O Lord, this bedchamber and all that inhabit it, and in your peace may they remain, and in your favour continue, and may they live in your love, and grow old and be increased in length of days." That was lovely, wasn't it? Let us all know how you get on with the whole thing. We need details. Want to say something? Please do, by leaving a comment. My good friend Anna Henderson speaks about her PhD project looking at modern embroidered histories inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry. Here's a link to the YouTube video. Anna, you're great!

Homunculus by Marguerite Heywood Homunculus by Marguerite Heywood I went to my artist friend's 60th birthday party yesterday ... and came away with a present of my own. This little (?) fellow, christened Homunculus by Marguerite Heywood, his creator, was introduced as supporting evidence for Marguerite's comment a few weeks ago on the subject of the naked figures in the Bayeux Tapestry. Marguerite implied that she produced Homunculus almost subconsciously, because, I guess, things deep and unbidden have to find an expression. How intriguing ... Is that, then, what lay at the root (terrible pun) of the genitally enhanced men in the borders of the Bayeux Tapestry? Did the borders allow the (? female) embroiderers the place and opportunity to express hidden desires? Were the borders sexually subversive spaces? If you're not into this kind of theorizing on a Sunday afternoon, that's fair enough. And maybe male genitalia just ain't your cup of tea (?!?!). But please understand that as the Anglo-Saxon Monk I had to find some way of intellectualizing my decision to put Homunculus and his equipment out there for all to see. I have my reputation to consider! Go on ... have your say. Do you like my Homunculus?

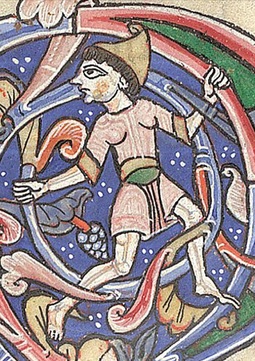

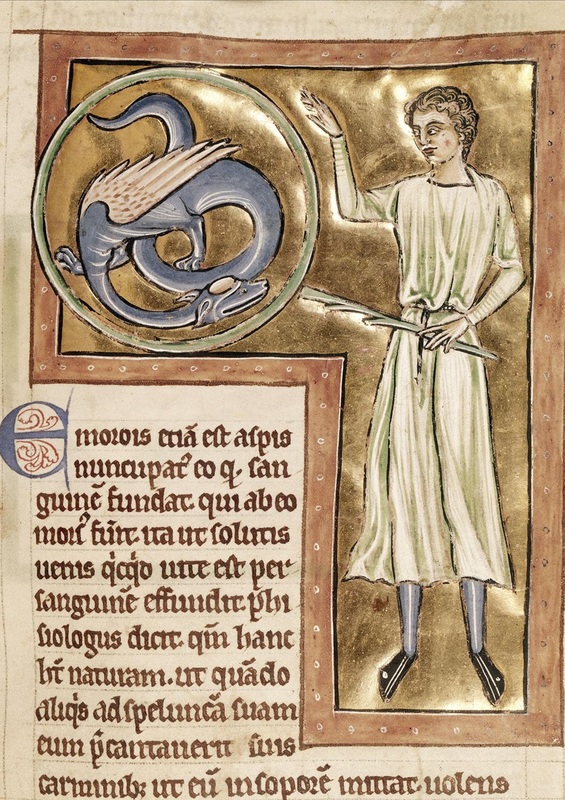

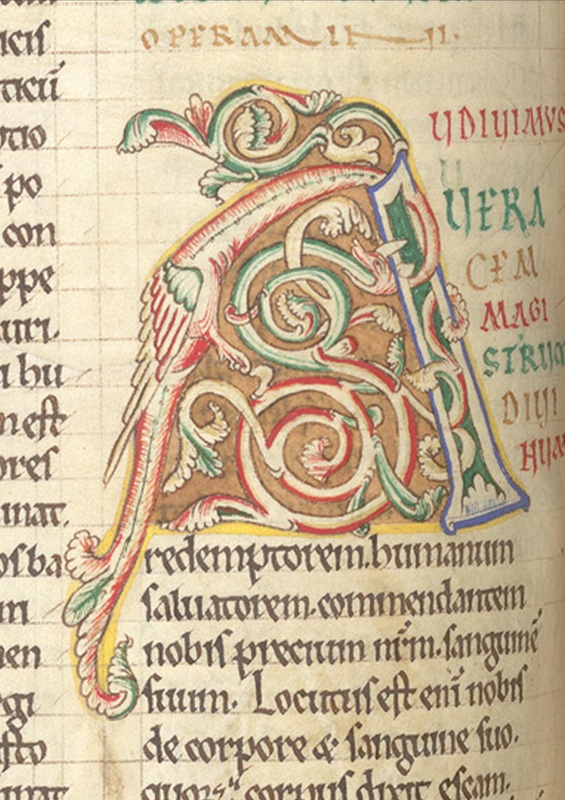

The Shaftesbury Psalter, British Library, Lansdowne 383 (England 1225-1250), folio 8v: detail of a dragon and men carrying wood The Shaftesbury Psalter, British Library, Lansdowne 383 (England 1225-1250), folio 8v: detail of a dragon and men carrying wood RON!” “DRACON!” I loved it when Merlin, played by the elfish Colin Morgan (those fabulous ears!), would command the presence of the scary-but-wise dragon. We need a few more old fire-drakes in our lives ... yes we do! I watched BBC’s Merlin pretty religiously – I am a monk in all I do. Alas! Early Saturday evenings have never quite been the same since it finished. We monks don’t get out much, you know. So to brighten up the gloomy cloisters of my mind, I thought I’d do a little something on dragons this weekend. This has nothing to do with the fact that I’m being intellectually lazy and just want to post a few pretty pictures from the British Library. No, nothing at all to do with that. Actually, I’ve been working very hard this week, and my studies have brought me into contact with a number of dragons – all new to me – and so I thought it only proper to share them with you. But before I do, just one more thing about Merlin ... Are you wondering why at the beginning I spelled dragon with a ‘c’ in the middle? Of course you are! Well, I’ve always been convinced that Morgan’s Merlin was using a Latinized version of the word. (You can disagree with me if you want – but you must leave a comment if you do.) He was always ready to use a few words of pseudo Old English whenever a bit of magic needed to be done. But I reckon when the script writers took advice (from some very lucky academic, no doubt), they decided not to go with the strictly Anglo-Saxon wyrm (from which we get the modern English ‘worm’). It would not have had quite the same ring to it, would it? I tried it myself in my back garden. My neighbours reported me. To the dragons/dracons/wyrms/worms! All images have been identified by the British Library as free from known copyright restrictions. l I call this one the Q Dragon, as he forms the tail of the letter Q (to make the word Quod). He's originally from Rochester and is dated to the first half of the twelfth century. The heads of medieval dragons are quite variable. Some look like lions, some are almost cute like a puppy. This one is a bit duck-billed, wouldn't you say? I like his knobbly, green spine which sprouts into a foliate terminus, posh words for a leafy end. His friends, by the way, are griffins. Meet Dragon H. Yes, that is the letter H, believe it or not. Capital H often appears in manuscripts like our modern lower case h. I think he (are dragons necessarily male?) is quite cute, puppy like. He seems a little in awe of the biting beasty at the top of the upright. He's also from Rochester, though from a different manuscript, which we can date to between the years 1108 and 1122. What is that man doing to that poor dragon? Looks like dragon abuse to me! This is a northern English dragon, or possibly from central England. He's from the first quarter of the thirteenth century. Now this really is dragon abuse! Yes, poor thing ... well, perhaps I should add that this is the archangel Michael defeating the dragon, who represents Satan (Revelation 12): so down the great dragon was hurled! He (we'll definitely go 'he' this time) is from Canterbury and dates to the third quarter of the twelfth century. Aha! Revenge is sweet! Meet Killer Dragon. Those needle teeth! This chap probably hails from Oxford and the first quarter of the thirteenth century. He's found in a Psalter. Dragons are almost ubiquitous in medieval liturgical books. This is Audi the Dragon. He forms the letter A for Audiviumus. (Apologies for my sadly deteriorating wit.) He is from Rochester and dates to the second quarter of the twelfth century. He has quite big ears, don't you think? I thought I would finish by providing you with incontrovertible, medieval proof that dragons were real (I think they may be extinct now). This fella, as you can see below, is found in a medical miscellany of a pharmocopeial compilation -- a herbal medicine book to you and me. As I said, incontrovertible evidence for real dragons. He does look kind of real ... a sort of medieval Komodo dragon, perhaps?

Well, that was great fun, wasn't it? There are tonnes more I could have shown you. But I do have a life, you know. Back to my scriptorium ... |

Details

|