|

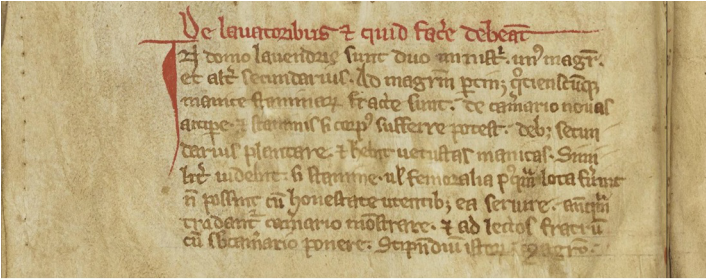

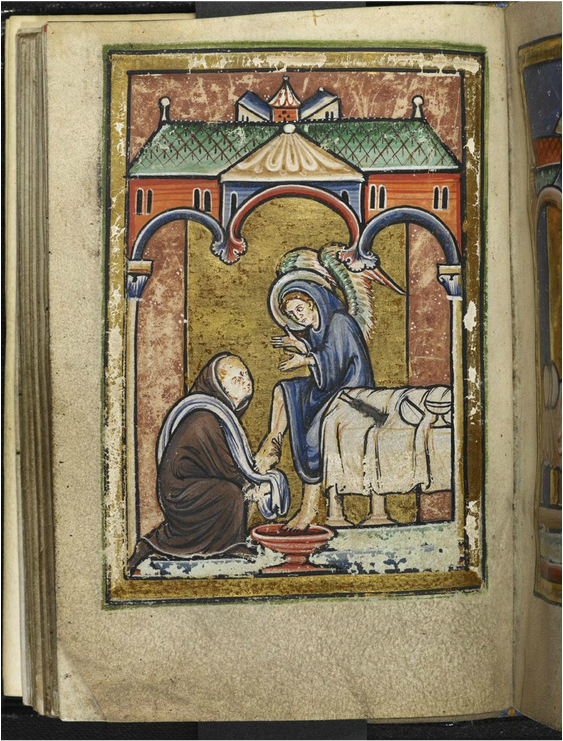

The Anglo-Saxon Monk lingers over the laundry duties of a medieval priory and discovers more than just soap and water Image: 'De lavatoribus et quid facere debeant', 'Concerning the launderers and what they must do', from Custumale Roffense, folio 59v (Rochester, late 13th-century). Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral. Blessed readers, I know many of you are of the opinion that medieval folk, even holy monks, were a smelly lot. No power-showers, no dry cleaning, and certainly no variable temperature selection with extra rinse option washing machines. I confess, I believe you're all slightly obsessed with washing in the twenty-first century, but I will pursue the matter no further. Rather, blessed ones, in order to disabuse you of your ill-formed prejudices, and to curb your tendency towards mental filth in general, I've provided below a short extract from the thirteenth-century Custumale Roffense, a customs book from the priory of Rochester Cathedral which includes a comprehensive description of the duties of the servants working for the Benedictine monks who lived there. Please note, if you do happen to be one of those rarely found readers with a delicate constitution, be advised that certain undergarments of the intimate variety are discussed in this text, and we will also be venturing beyond things which twenty-first century folk would associate directly with cleaning and washing. Yes, blood-letting! Image: Blood-letting, Luttrell Psalter, British Library 42130 (Lincoln, 2nd quarter of 14th century), folio 61r. Public Domain. Click on image to go to source. Concerning the launderers and what they ought to do In the laundry house there are two servants, one master and also a second rank servant. Whenever the sleeves of undershirts are torn, it belongs to the master to receive new ones from the chamberlain; if the body of an undershirt can be re-used, the second rank servant must store it, and he will have the old sleeves. Likewise, he will check if undershirts and under-breeches, after they have been washed, cannot with honesty be made serviceable, before they are handed over to show to the chamberlain and put at the beds of the brothers by the sub-chamberlain. Their wages: to the master 4 shillings, to the second rank servant 3 shillings. And when the brothers go to bathe, they [i.e. the servants] ought to have ready everything for this which is necessary. They supply soap for the brothers for shaving. It belongs to the lad-servant to make the lye. His role is to make the fire before which the brothers must be bled, and to summon the blood-letter, in order that he may be prepared to bleed the brothers. The master also sews the names of the brothers in their undershirts and under-breeches. These two have a Christmas fire for the Nativity, just like the tailors. Translation by Christopher Monk, © 2016 So as you see, blessed ones, the brothers in this thirteenth-century priory knew how to look after their undies. Not only were they washed and checked over by the servants but they were inspected by the chamberlain (a senior monk in charge of clothing) before the sub-chamberlain delivered them, freshly laundered and darned, back to the brothers' beds. Presumably the sub-chamberlain was as literate as the laundry master and so was able to read the name labels and match the right undies to the right brother. Laundered or not, you wouldn't want to get someone else's, now would you? I should probably point out that Rochester priory had quite a lot of different workshops, due to the architectural expertise and enthusiasm for building of its first prior, Gundulf, so it would seem that the laundry was done in a dedicated laundry house. You might be tempted to think that this text suggests that is also where the brothers did their own personal bathing, but I imagine this was something they probably did in the cloister, though I may be wrong. At any rate, the launderers had the responsibility to make sure the brothers' bodies were kept as clean as their underclothes, and so they fussed about them making sure they had all they needed for bathing, including the soap for shaving their tonsures. The soap came in the form of lye, of which, I'm quite sure, you users of fancy, twenty-first century shower gels have no idea. Well, lye was a detergent formed from wood ash. Sounds delightful, doesn't it? Finally, the second rank servant, whom the text suggests would have been just a lad, maybe the master launderer's son (no washerwomen here), looked after the fire to keep the brothers comfortable when the nasty blood-letter arrived. Bloodletting for all sorts of ailments was quite the thing at this time, and indeed was practiced earlier by the Anglo-Saxons too. In fact, in the Custumale Roffense there are several medical texts including one that regulates the best times in the year to perform bloodletting for animals and humans. But as all this talk of blood is making me squirm – I really am a delicate soul, blessed ones – I shall leave the further details on that for another post. In the meantime, I've kindly provided below a sampling of medieval images which illustrate that medieval folks were not averse to cleanliness. Alright, I admit that the angel in the Cuthbert scene looks a bit annoyed that all he's getting washed are his feet, and it's fair to say that the mighty handsome tub in the next image, within which that gentleman is situated, is perhaps not enormously representative. As for the final image, well, I would suggest that you don't look too closely at the details. I just feel sorry for the young man who's dropped the soap! May the Lord bless you all. Image: Young Cuthbert washes the feet of an angel who is in the guise of a traveller. From The Prose Life of Cuthbert, British Library, MS Yates Thompson 26 (Durham, last quarter of the 12th century), folio 17v. Public Domain: click on image to go to the source. Image: Woman bathing a man, letter B for balneare (to bathe). From the encyclopaedia Omne Bonum (Circumcisio-Dona Spiritui Sancti), British Library, MS Royal 6 E vi ( ), folio 179r. Public Domain: click on image to go to the source. Patients bathe and drink spa waters. From De balneis Puteoli, Vatican City, BAV Ross 379 (14th century), folio 21r.

Public Domain: click on image to go to the source.

9 Comments

Matt Dubuque

3/7/2016 02:46:39 pm

This is fine, but the life of monks was not representative of the general population, whose lot was far worse during this time of the Black Death, according to Hollinshed.

Reply

Chris (The Anglo-Saxon Monk)

3/7/2016 04:39:31 pm

You're quite right to suggest that the life of monks during the period of the Rochester Customs book (which was mostly written in the late thirteenth century) was not fully representative of the general population. Certainly, when we compare the monastic life of these Benedictine monks with that of their counterparts in the Anglo-Saxon period (thinking here 10th and 11th century, after the Benedictine Rule was widely adopted in England), then broadly it would seem that these later monks were less involved in the physical labour of the monastery, and life seemed a little more comfortable.

Reply

SueAnn DeVito

5/7/2016 01:10:31 pm

Fun fact, as late as 2004, servants of the house still had occasion to sew the name of at least one of those serving in the Cathedral into his underthings! (My son was a chorister in 2003-2004, and lived in the school boarding house)

Reply

Chris (The Anglo-Saxon Monk)

6/7/2016 02:47:18 pm

Thanks SueAnne for leaving a comment.

Reply

Chris (The Anglo-Saxon Monk)

6/7/2016 02:50:55 pm

Oops! SueAnn, not SueAnne! Sorry.

Reply

18/10/2018 06:26:42 pm

I'd have to check with you here. Which is not something I usually do! I enjoy reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

Reply

26/6/2022 10:59:33 am

Hello Frances, thanks for contacting me.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|