|

Blessed ones, Dr Monk's translations of the early English laws from the Textus Roffensis manuscript are now available via the Kent Archaeological Society's (KAS) website.

0 Comments

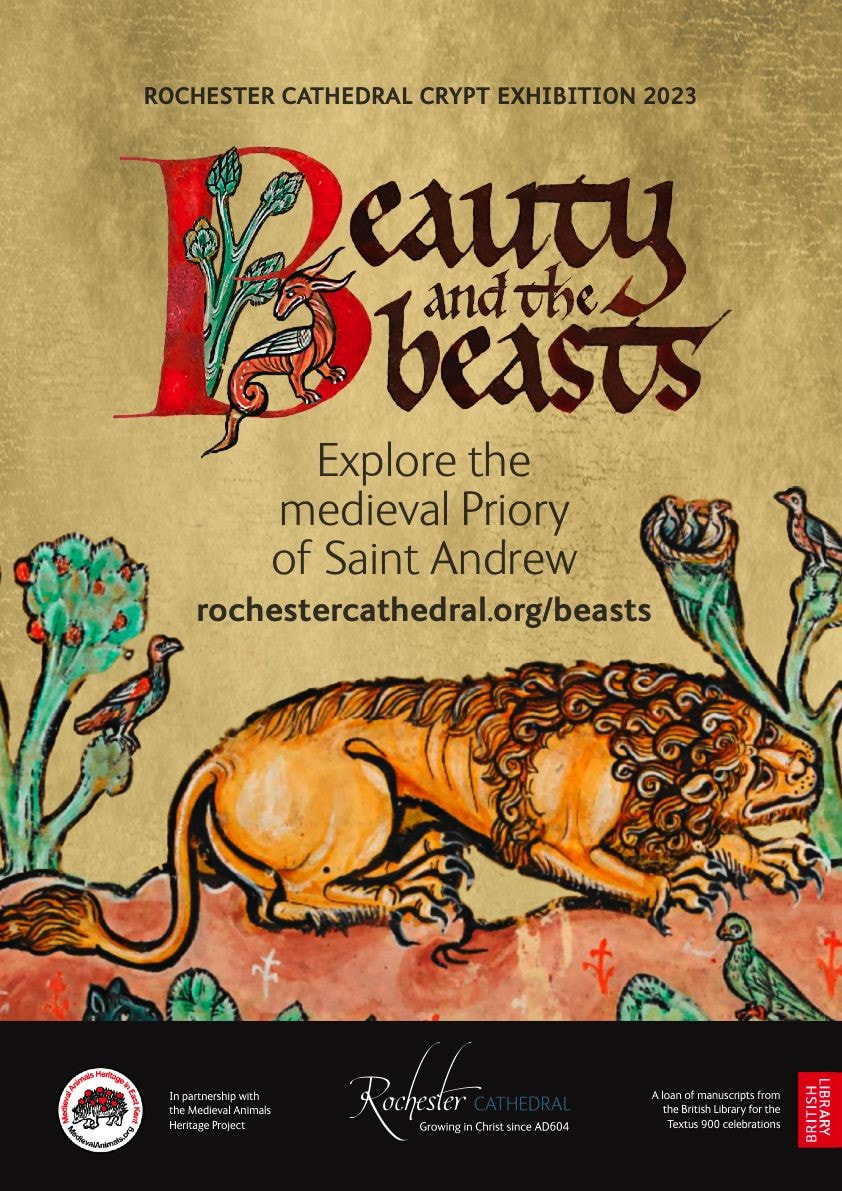

Dr Monk produced a new video about Textus Roffensis, which was shown as the keynote address at the 2024 annual CALCA (Cathedral Archives, Libraries & Collections Association) conference, held at Rochester Cathedral on June 7th. As well as giving an overview of the importance of this legal encyclopaedia, Dr Monk digs into some of its details, taking a closer look at the way thieves were punished in early medieval England. King Athelstan's treatment of young offenders is chilling! New Exhibition at Rochester Cathedral Blessed ones, The other Monk of this website, Dr Christopher Monk, asked me to pass on some information about a new exhibition he has been working on. Well, I know he's been very industrious this last couple of months, so I said yes. One has to be gracious. Rochester Cathedral has opened its crypt exhibition space to three British Library Manuscripts: the Rochester Bestiary, the Rochester Bible, and Elizabeth Elstob's 18th-century copy of excerpt from the 12th-century Textus Roffensis. The manuscripts are in the exhibition until the end of October 2023. Entitled 'Beauty and the Beasts', the exhibition explores its theme broadly, not only presenting the visitor with the beautiful illustrations of beasts from the three manuscripts, but also presenting material about the importance of beasts – domestic farm animals, in particular – to the lives of the monks that lived in the medieval cathedral priory at the time when the very manuscripts they were producing (from animal skins) were being prepared and crafted. My role as the primary consultant was to write both hard copy for the physical exhibition and online material for 'Learn More' activities. You can find my commentary on the Rochester Bible and Elstob's excerpts, along with that of other contributors on the Beauty and the Beasts web pages. For information relating to the importance of domestic animals in the history of Rochester Priory, head to the Farming and Food pages.

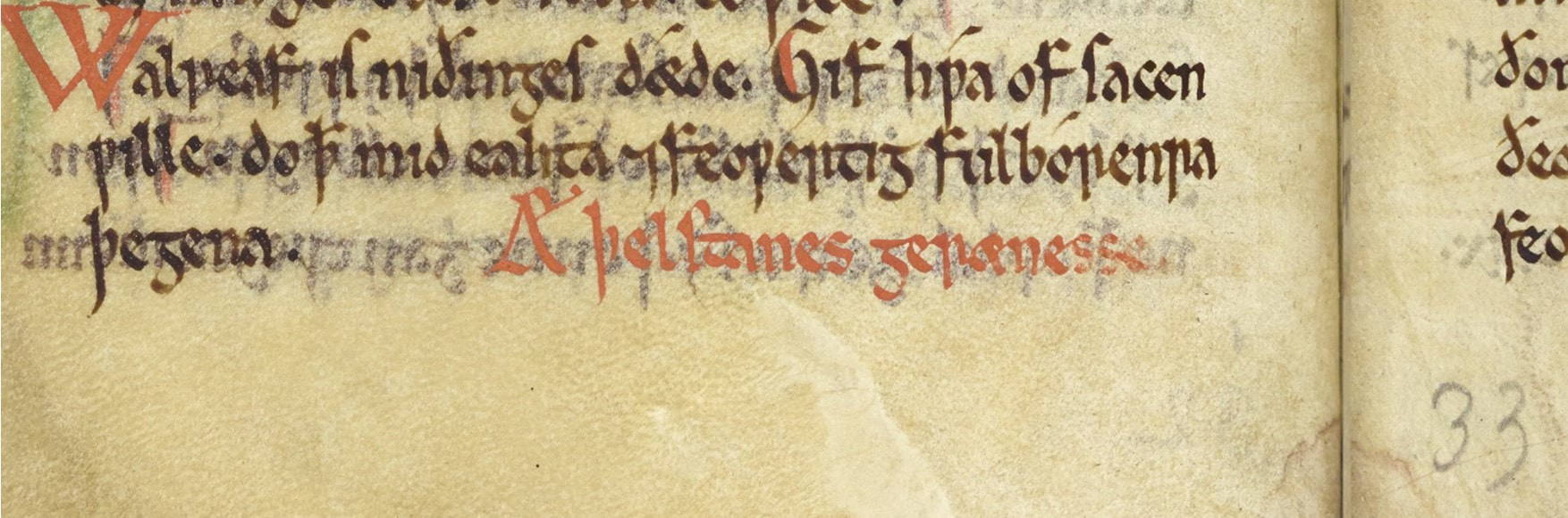

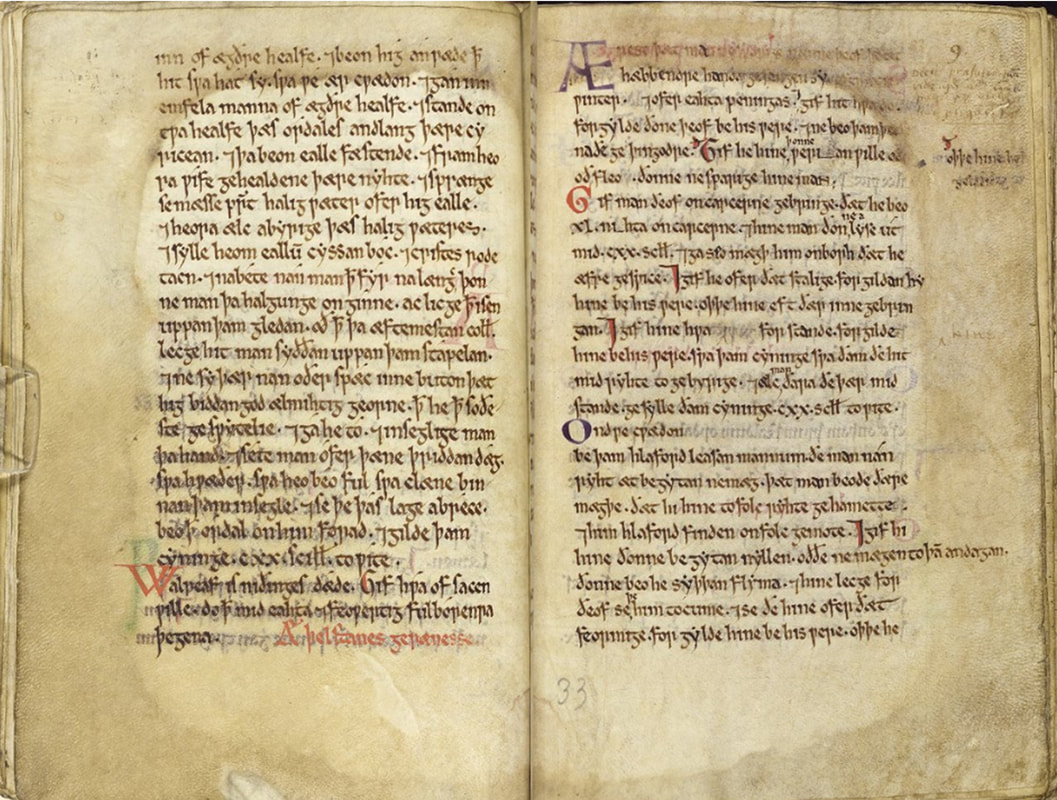

The Medieval Monk casts his eye over the new translation of King Æthelstan's laws  Æthelstan’s Grately Code. It begins with the title ‘Æþelstanes gerænesse’, ‘Æthelstan’s laws’, in red ink at the bottom of the left page (see detail below). Textus Roffensis, folios 32v-33r, Dean and Chapter of Rochester Cathedral. The Grately Code continues for a further eight pages, as far as folio 37r. Screenshot of digital facsimile, Manchester, John Rylands Library. Blessed ones, I bring you a bounteous supply of Old English laws. What more could you ask for? Don't answer. The other Monk of this website, Dr Christopher Monk, has been busy transcribing and translating more material from Textus Roffensis, the fullest set of early medieval English laws written in the vernacular. There are three new translations, the main one being the major set of laws by King Æthelstan, 'king of the Anglo-Saxons and Danes', 924/925-927, and 'king of the English, 927-939. This text is known today as the Grately Code. The other two laws, produced around the same time as the Grately Code, are anonymous and much shorter: Be blaserum ⁊ be morðslihtum, which is all about dealing with nasty arsonists and murders; and Forfang, a fragment from a law concerning the reward for retrieving stolen property. Now Dr Monk, in his introduction to the Grately Code, highlights a couple of important aspects of Æthelstan's foundational law. He talks about trial by ordeal and the phrase 'disobedience to the king'. Yes, yes, all very good. But to my mind there are two really important laws that seemed to have escaped his notice. So read on, beloved ones. Selling horses No person may sell any horse overseas, unless he wishes to gift it. (Grately Code) Now, let me tell you a story. Our tenth-century 'king of the English' didn't mind accepting a gift horse, or even ‘many’ a gift horse, from over the gannets' bath, or whale road, or whatever you want to call the sea. Indeed, according to William of Malmesbury, writing in the 1120s, Hugh the Great, ‘king of the Franks’ – well, actually, he was a duke, Willy – wanted to wed Æthelstan’s half-sister, Eadhild. So to seal the deal with this princess, ‘in whom the whole mass of beauty, of which other women have only a share, had flowed into one by nature’ – you can see Willy Malmesbury setting things up here very nicely, can’t you? – Hugh sent an embassy across the swan road to the king to strike a bargain for the betrothal, not troubling himself in person, of course. Well, Willy tells us his delegation ‘produced gifts on a truly munificent scale, such as might instantly satisfy the desires of a recipient however greedy’ – what’s he saying about our good king? Well, anyway, what did Æthelstan get in return for handing over his beloved, all-too-beautiful sister? ... the fragrance of spices that had never before been seen in England; noble jewels (emeralds especially, from whose green depths reflected sunlight lit up the eyes of the bystanders with their enchanting radiance); many swift horses with their trappings, ‘champing between their teeth’, as Virgil says, ‘the tawny gold’; an onyx vessel so modelled by the engraver with his subtle art that one seemed to see real ripples in the standing grain, buds really swelling on the vines, men’s figures really moving, shining with such a polish that it reflected the face of the beholder like a mirror; the sword of Constantine the Great, etc, etc, etc, etc.’ And I thought I went on some times! But if you're desperate to know what else was given... There was one of the nails of the cruxifiction, attached to the pommel of Constantine's sword; Charlemagne's lance; the banner of Maurice the martyr; a piece of the Cross enclosed in crystal; a bit of the crown of thorns; and a solid gold crown which was 'yet more precious from its gems, of which the brilliance shot such flashing darts of light at the beholders that the more anyone strove to strain his eyes, the more he was dazzled and obliged to give up'! Oh, for Heaven's sake, Willy! We get it! Dazzling stuff. Thankfully, Willy does eventually tell us that King Æthelstan was delighted with his gifts – though the horses did make a mess in his court, though no one noticed because of all the dazzling going on (I made that bit up). In response, the king reciprocated ‘with gifts that were scarcely less’ – of course he did. And, moreover, he ‘comforted the passionate suitor’ – so passionate he couldn’t bear the journey himself – ‘with the hand of his sister’. Aw, lovely. So, there you go. Gifting and receiving gifts of horses was fine. But no horse trading overseas. Why exactly, we are not told in the Grately Code. Possibly it was something to do with the importance of horses to the internal economy of England; or it was that horses were in short supply and needed by the army (Cronenwett, p. 109). Sunday tradingAnd [we declared] that there be no trading on Sunday. If then anyone does this, he should forfeit the goods, and pay 30 shillings as a fine. (Grately Code) Now, there are the crimes of arson, murder by witchcraft, and treachery to one’s lord, but Sunday trading! Well, that really takes the biscuit, as the other Monk would put it. I do hope his biscuits weren’t bought on the Sabbath day. He didn't say. You see, what could be more unchristian than labouring – nay, trading – on the Lord’s day? Never mind treachery to one’s earthly lords, I think that such behaviour amounts to far worse. And if I had written the Grately Code for Æthelstan, I would have sent all offenders straight to the threefold ordeal (you can learn more about that from Dr Monk’s introduction). That’s all I have to say on the matter. Now, where did he put those biscuits? Chocolate, gluten free, they were. Cited works Cronenwett, Philip Nathaniel, 'Basileos Anglorum: a study of the life and reign of King Athelstan of England, 924-939' (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 1974); available here. William of Malmesbury, The Deeds of the English Kings, edited and translated by R. A. B. Mynors (London: The Folio Society, 2014).

New translation of the king's modification of the death penalty now available Blessed ones, King Æthelstan (‘king of the English’ 927-939) is known for his severe treatment of those caught red-handed as thieves. They were executed. The king, however, had second thoughts about the age at which a thief could be put to death, and also about the minimum value of the property stolen which could lead to execution. As a result, he modified a previous law of his own to reflect his change of mind on the matter. But don’t go thinking Æthelstan was some big soft-hearted ruler. Blessed ones, I really don’t think you good folk of the twenty-first century would detect much in the way of compassion in this powerful king’s soul. After all, even after the modification had been made, you could still be executed as young as 15, and for as little as 12 pennies, if you were caught in the act of stealing. And if you were younger than this, and the amount was smaller, you could still yet lose your life if you resisted arrest or attempted to flee. It really was, as the legal historian Tom Lambert puts it, ‘a distinctly merciless order’ that Æthelstan ushered in. A copy of Æthelstan’s modification for theft, originally written probably between 930-939, is uniquely preserved in Textus Roffensis, the ‘book of Rochester’, which was compiled around the year 1123 and is cared for by Rochester Cathedral. Now, for the first time, there is an accessible modern English translation of this particular text within Æthelstan’s laws. This translation, along with commentary and notes, has been authored by the other Monk of this website, Dr Christopher Monk. All you need to do in order to read the new translation is follow the first link below. And if you want to catch up with the ongoing programme of translations of and interpretative articles about Textus Roffensis, you can follow the second link.

|

Details

|