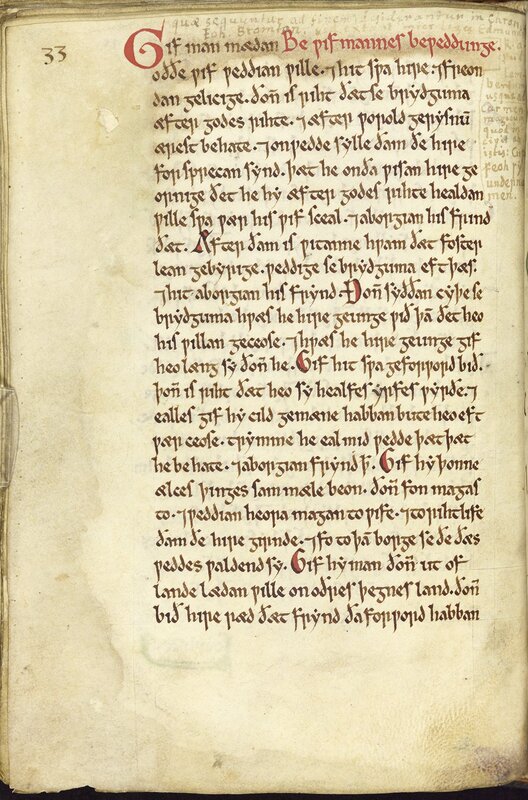

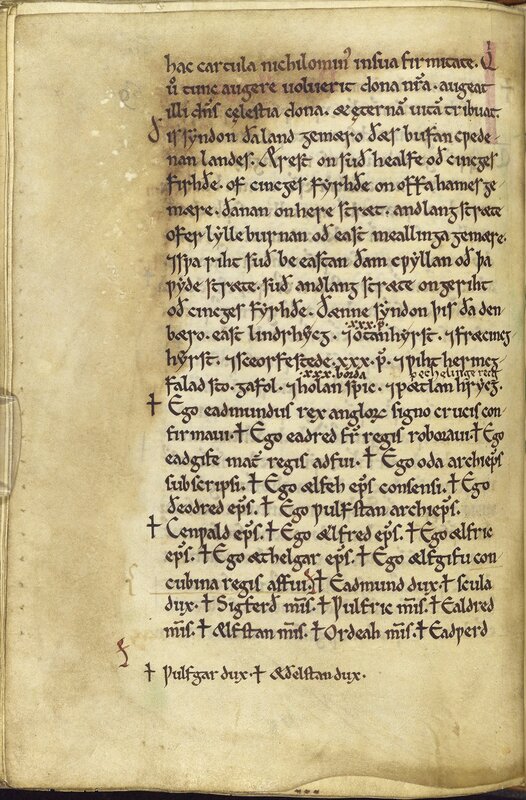

'Concerning a woman's bretrothal' & a charter of Edmund I Blessed ones, The other Monk of this website has been busying away with translating Textus Roffensis ('the book of Rochester'). Here are the latest texts: This is a particularly fascinating text. It will let you know what had to happen when a man wanted to marry a woman in England in the decades leading up to the Norman Conquest. Lots of pledging, I can tell you. And when it came to the officiating priest at the wedding, he had to make sure the couple were not too closely related. Oh, just the thought of such scandal! This is a somewhat spurious charter, as Dr Monk's introduction makes clear, but nonetheless of great interest because of its Old English boundary clause which directs one around the piece of land being gifted by Edmund to the bishop of Rochester. As you read it, you can imagine someone perambulating from landmark to landmark. Also, the charter's witness list is noteworthy for its inclusion of both the queen mother and the queen consort of Eadmund.

0 Comments

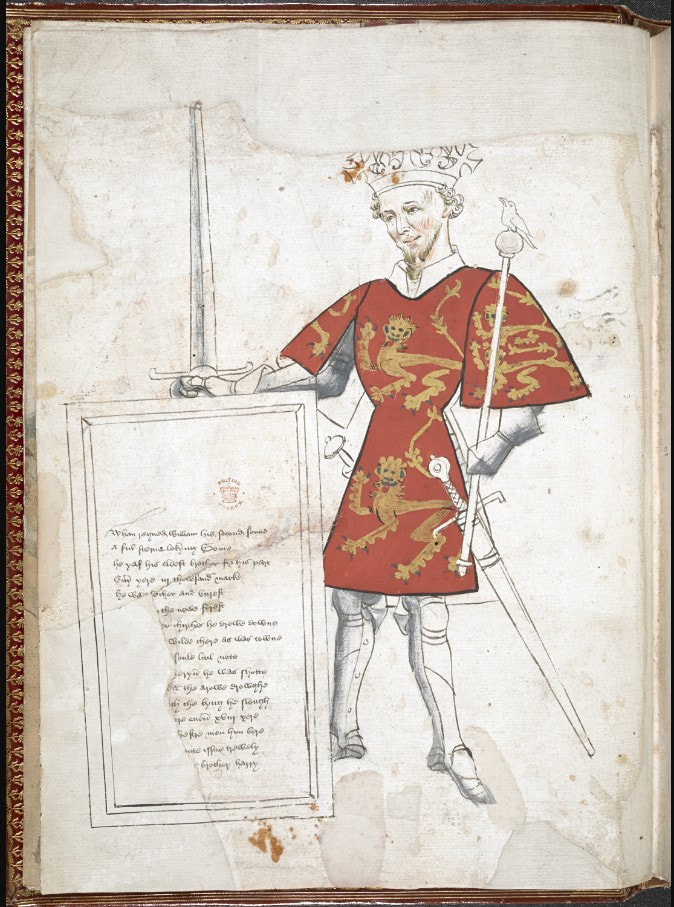

New translations from Textus Roffensis Blessed ones! I am aware of the great sadness many feel at the loss of Queen Elilzabeth II, so I will not dwell on my subject today, that of the eleventh-century monarch William II (aka Rufus, r. 1087-1100), in my normal freewheeling way. But if you would like to read the story of how Bishop Gundulf of Rochester and Archbishop Lanfranc withstood, with much zeal, the royal negotiations regarding the manor of Haddenham (which was the single most important manor held by the monks of Rochester), then follow the links below. Here are three new translations of texts relating to the Haddenham narrative; the records are preserved in Textus Roffensis, the Book of Rochester. The first is a revised translation by Dr Monk, with new commentary, of the Rochester monks' record of events surrounding the argy-bargy over Haddenham. Let's call it their version of the story. The second and third translations are published together, and are a result of Dr Monk collaborating with Jacob Scott of Rochester Cathedral. Dr Monk provides the introduction and notes and the transcription and translation of the second text; Jacob, the transcript and translation of the first text, which Dr Monk has edited. Their thanks go to Elise Fleming for proofreading duties. The two texts are the confirmation by William II of Lanfranc's grant of Haddenham to the monks of Rochester; and Lanfranc's own sanctioning of the king's confirmation. There's a rather nice anathema at the end of Lanfranc's sanction, if you're into that kind of thing, I should say!

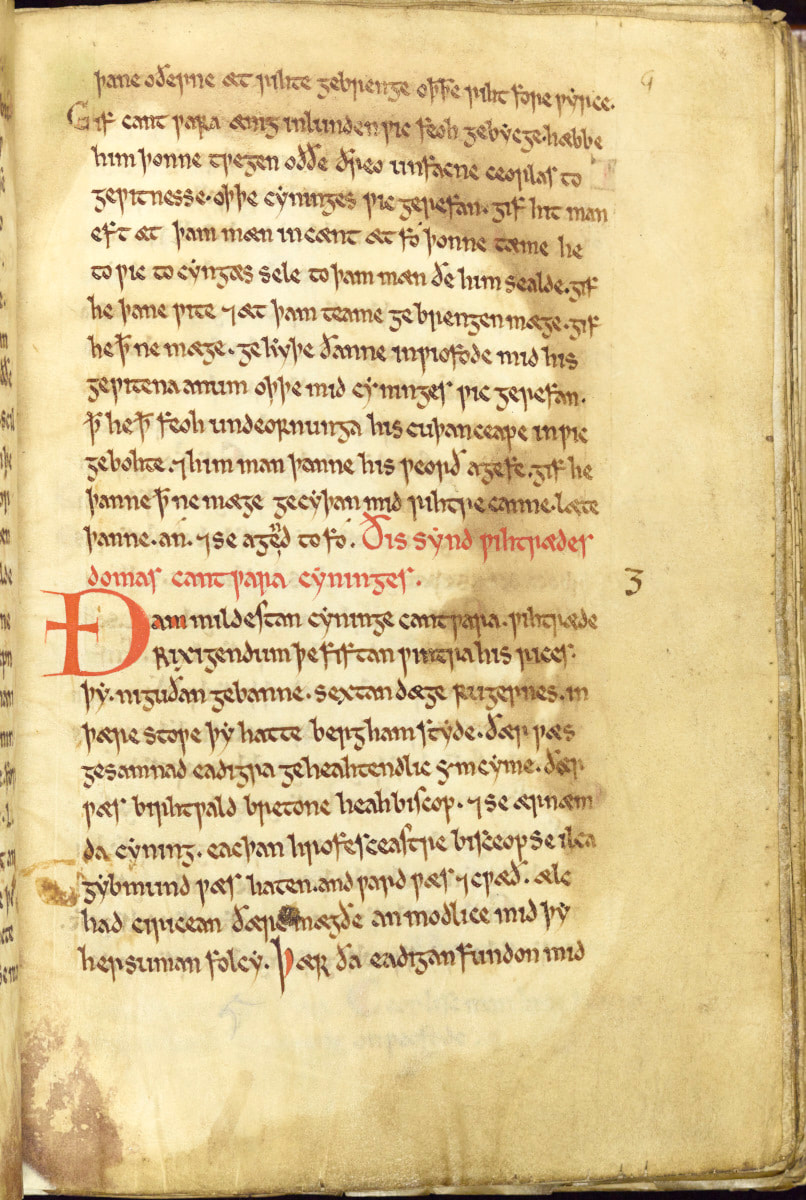

New translation of the law code of King Wihtræd of Kent Blessed ones, It has not yet been a week and yet I am returning with the news of another translation by Dr Monk – the less than virtuous fellow with whom I share this blog. This time, beloved souls, it is the third and final law from the Kingdom of Kent: the Laws of Wihtræd. Even I don’t know that much about King Wihtræd. But I can say that he ruled Kent for quite a long time, from either 690 or 691, of the year of our Lord, to his death on the 23rd April 725. For the first couple of years, or so, he was having to share the throne with a certain Swæfheard, an impertinent invader from the kingdom of the East Saxons, whose father ruled part of that kingdom and, as it happens, became a monk after 30 years of rule. A decent fellow, obviously. But I don’t much care for his son. Anyhow, back to King Wihtræd… And what I have to say is that the laws of this good king reveal to us that he was very concerned about the Church and the practice of the Christian faith among his people. May we all be like good king Wihtræd! We find right at the outset of his decrees that the Church was to be free from taxation. Did that really need to be written down, I ask? And then there are rulings against worshipping ‘devils’ – oh my! - and judgements concerning the breaking of Church laws on fasting and the Sabbath day. Oh, Heaven preserve us! King Witty – I’m sure he would forgive my mildly impudent familiarity – even goes as far as to encourage folk to dob in their neighbours! Should someone actually ‘discover’ their neighbour has been working on the Sabbath – the Lord’s day of rest – then, if he does the dobbing in, he gets to keep half of the fine that was destined for the public coffers. I reckon I would be shillings in if we had that rule in and around my monastery. But I digress. The final fascinating thing I wish to share with you about this set of laws comes from Dr Monk, and really there’s no surprise that it relates to fornication! Yes, he knows more than he should about this subject (see the link, below). Leaving that aside, I should say that Dr Monk kindly informed me that Wihtraed’s laws are the first among the surviving early English laws to (attempt to) regulate the unriht hæmed – that’s ‘unlawful sexual union’ to you. That would have meant that folk who married someone to whom they were too closely related were in big trouble – no marrying of cousins, that’s for sure, and maybe not even your second cousin once removed! I don’t even know who my second cousin first removed is. And as for those who dared to commit bigamy – sending their spouse away just because they wanted a new one – well the fires of Gehenna were not sufficiently hot for them. Alright, Wihtræd didn’t quite put it like that, but you know what I mean. Well, before I tell you everything that is in this set of Kentish laws, I should direct you to where you can find Dr Monk’s translation. Included is a transcription-edition of the text and numerous notes. There are always loads of those. May you all be blessed – and no unlawful unions, now! I will find out! Postscript Oh, if you fancy reading more about unlawful sexual unions, a free journal article by Dr Monk is available here. And if you would like to show your appreciation and support for the research that goes into this website you can make a one-time donation on the Buy Me A Coffee tab. Thank you.

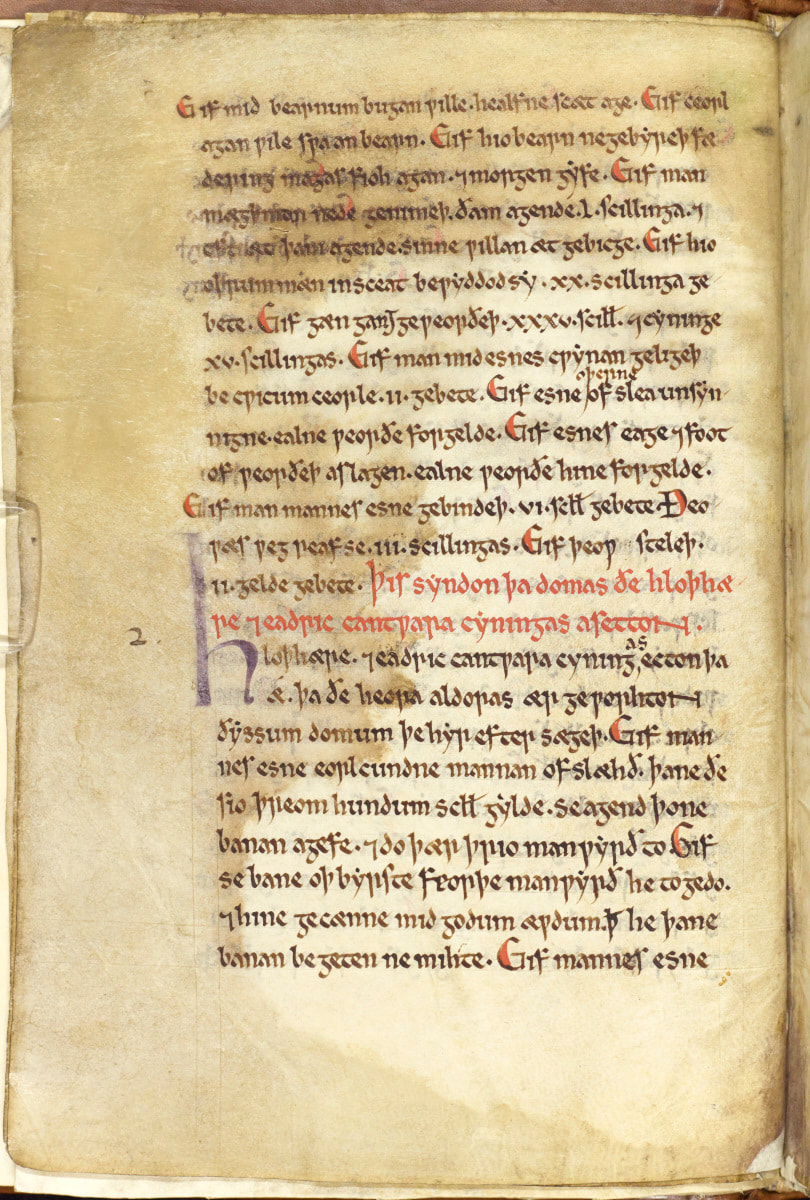

New translation of the seventh-century law code  The twelfth-century scribe has written a heading, in red ink: 'These are the judgments which Hlothere and Eadric, kings of the Kentish people, set down.' The large purple 'h' [Hlothere'] marks the beginning of the text proper. Textus Roffensis (Rochester Priory, c. 1123), folio 3v. Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter, Rochester Cathedral. Blessed ones, The other Monk of this website has been busy with the manuscript known as Textus Roffensis, that is, the Rochester Book. The law codes that make up the first part of this early twelfth-century manuscript have recently been added to the UNESCO Memory of the World UK Register, which you can read about here. Dr Monk has been working on and off with the custodians of the manuscript, Rochester Cathedral, during the last eight years or so. Presently, there's a new push to get the whole of the manuscript transcribed and translated, including the charters and records of the second part. This will all be accessible through the cathedral website. There's already quite a lot of stuff on the Textus Roffensis pages, so do check it out. The latest set of laws that has been published by the cathedral is that of Holthere and Eadric, uncle and nephew, who consecutively ruled the kingdom of Kent at the end of the seventh century. These laws only survive as a copy in Textus Roffensis. They are so important for helping modern historians understand this early period in English history. Of course, being an eleventh-century monk, I myself am closer to the action, to borrow one of your idioms, but does anyone ever ask me about all this stuff? They do not. Be that as it may, I must not yield to the temptation to grumble, so please enjoy the latest instalment of Dr Monk's Textus Roffensis translations:

Blessed ones, The other Monk has been busy over at Monk's Modern Medieval Cuisine. He has produced two new things related to the Benedictine monks of St Andrew's Priory, Rochester. First, a video about a flan. Yes, every Easter the beloved brethren of Rochester gave a delicious dairy flan to one of their chief servants, the master miller (who doubled up as the master baker). So follow the video below to find out how you can make it yourself. Needless to say, I have already had a piece. There have to be some perks to this job. And, secondly, he has just written a post about the monastic consumption of quadrupeds! Oh, blessed ones, I must right now, if you would permit me, indulge in a shiver of embarrassment, nay shame, for my Rochester brothers have succumbed to eating meat on a regular basis. (Back of hand to head moment.) Here, in the eleventh century, we monks are faithfully adhering to St Benedict's Rule, forbidding the eating of such meat except when we are gravely ill. But as Dr Monk explains, there has been quite a shift in attitudes in Rochester by the early thirteenth century. Admittedly, quite a few of my contemporaries here do appear to fall dangerously ill with alarming consistency only to return from the infirmary a week later rejuvenated by flesh. But I must not judge. It is beneath me. So, blessed ones, if you care to read the gory details about the St Andrew's monks and their carnivorous habits, just follow the link below. May you all be blessed.

|

Details

|