|

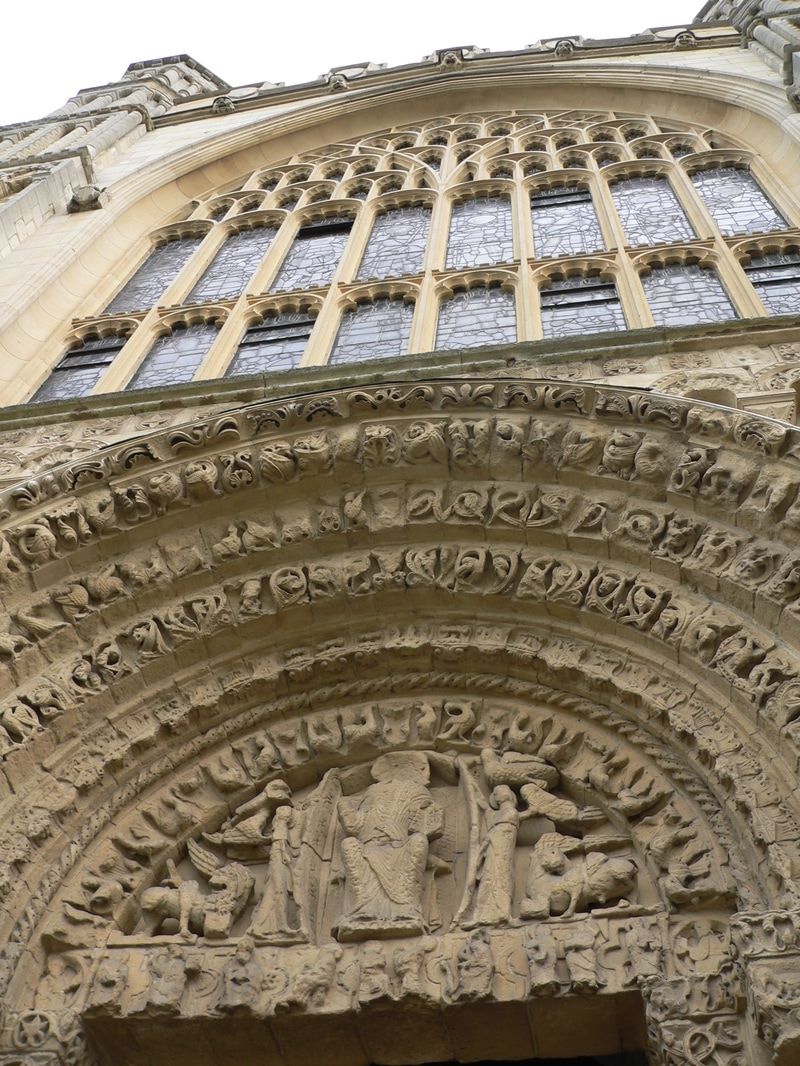

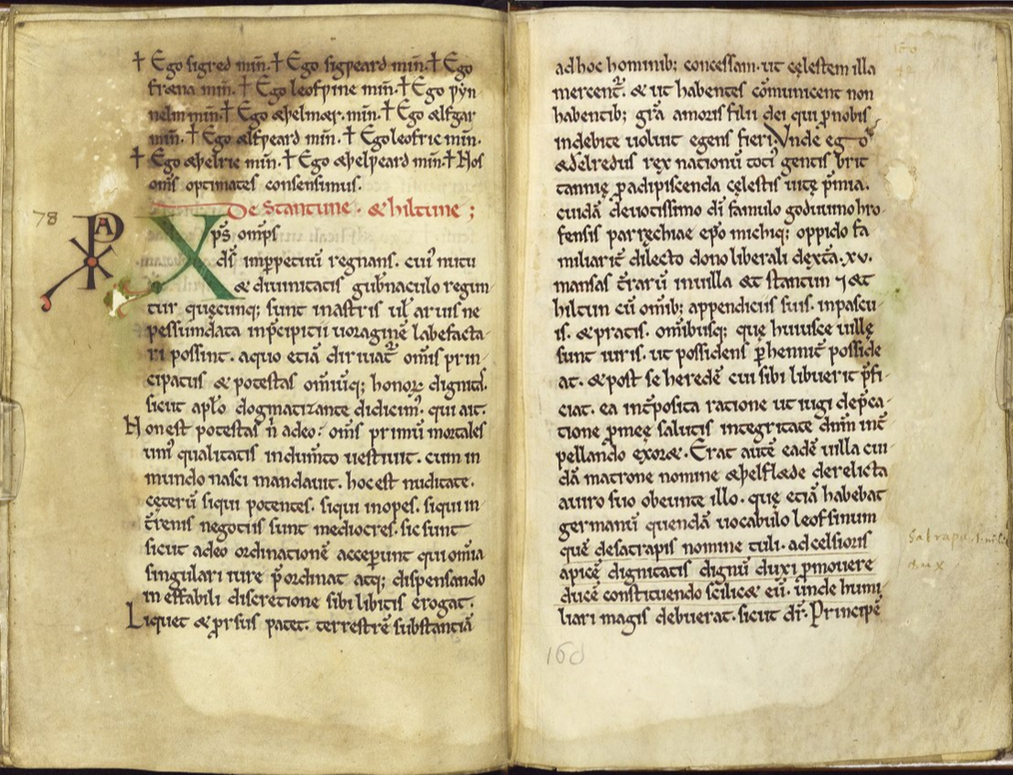

In the first of a series, the Anglo-Saxon Monk invites his alter ego to pick out his highlights from a recent visit to Rochester Cathedral. What a wonderful time I had at Rochester Cathedral last week. I spent three days delivering workshops and talks about two of the cathedral's remarkable medieval books: Textus Roffensis, which contains copies of English laws and other legal documents, the earliest of which goes back to the year AD 600; and Custumale Roffense, a thirteenth-century customs book, which deals with the everyday lives and the livelihood of the monks at Rochester priory. The audiences for the workshops were made up primarily of cathedral volunteers, who are, quite simply, outstanding. The cathedral would not function as it does without them. They made me feel very welcome and there was a remarkable interchange of enthusiasm and knowledge as we looked at Rochester's two treasures. What I'm going to do over the next few weeks is provide a few highlights from the workshops and the public lecture I also gave: a few snippets, if you will, which appeared to capture the imagination; and then I shall expand upon these a little. So let's start with one of the charters in Textus Roffensis: So here's a copy of a charter, a royal diploma granting land, that dates to 1012. It's one of four in Textus Roffensis written for King Ethelred the Unready. All four are marked out by a chi-rho symbol; in fact only those by Ethelred are marked out this way. What's a Chi-Rho? As the video above shows, this symbol, also known as chrismon, is a monogram formed from the first two letters of the name 'Christ' in Greek, chi (looks like 'X') and rho (looks like 'P'). What is different about the one appearing in the charter we are looking at, on folio 159 verso, is the incorporation of the letter 'A' inside the eye of the rho. Is this significant in some way? Before I answer that, let us just trace the history surrounding this charter... a history involving the Vikings and murder! The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tell us that in the year 1011, 'between the Nativity of St Mary [September 8th] and Michaelmas [September 29th]', a Danish army besieged Canterbury, capturing 'the archbishop Ælfheah, and Ælfweard the king's reeve, and Abbot Leofwine, and Bishop Godwine [of Rochester]. And they seized all ordained people, both men and women'. The archbishop was taken back to the Viking ships by the men of the leader, Jarl Thorkell, or Thorkell the Tall, as he was also known. He was kept there until Easter the following year and, after refusing to be ransomed by the good people of England, Thorkell's men murdered him during a drunken assembly, pelting him, we are told, 'with bones and the heads of cattle' until one of the men 'struck him on the head with the butt of an axe.' The account reaches for poetic rhetoric in order to convey the terrible happenings: 'There wretchedness might be seen where earlier was seen bliss, in that wretched town from where there first came to us Christendom and bliss before God and before the world.' The regaining of lost 'bliss' is something that the charter of Ethelred alludes to. Before I elaborate, however, we just need to know a little more about the circumstances surrounding its beneficiary. It was Bishop Godwine, whom we have seen was seized by the Danes in Canterbury, who was to receive fifteen hides of land in 'the villa at Stanton and at Hilton' along with all their appurtenances. So though we do not know what happened to him whilst he was in captivity, we know Godwine, in contrast to the archbishop, was safely returned to his position at Rochester. As it happens, the land Godwine was being granted by the king had been forfeited by a certain Æthelflæd, sister and supporter of the outlawed Ealdorman Leofsige, who had been, we are told in the charter, exiled by the king for murdering the king's reeve Æfic. When exactly Æthelflæd forfeited her lands, inherited from her husband, we do not know, but by the time of this charter, in 1012, her estate was evidently in the hands of the king, and he was free to grant portions of it to the freed Godwine. When we look at the list of witnesses of the charter, we see named there King Ethelred and Queen Ælfgifu (also known as Emma), but sadly no Archbishop Ælfheah, but in his stead Wulfstan, archbishop of York, who takes the lead 'with our fellow bishops', including Godwine himself, 'and the king's sons, and the abbots, ealdormen, and thegns whose names are given below'. The absence of the archbishop of Canterbury acts as a sombre note to the documenting of the charter proceedings which, more positively, seem to represent a return to peace in the kingdom. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tell us that in 1012 the 'tax [tribute] was paid, and oaths of peace sworn, [and] the raiding-army dispersed as widely as it had been gathered earlier.' Moreover, following a remarkable defection by Thorkell to the side of Ethelred, '45 ships from the raiding-army submitted to the king, and promised him that they would guard this country.' Ah! It would seem peace (of sorts) had arrived, at least for a while. Probably, it is that very peace which is being invoked in this charter, which was likely written shortly after the events at Canterbury. Moreover, it is in the symbol of Christ, in the charter's chi-rho, that we witness this invocation of peace... for if we look very carefully, and play around with the lettering, what do we behold? Yes, as the video above shows, a word game is being played in this charter! The Roman 'A' was evidently inserted into the chi-rho to trigger a response, one that allows the Greek letters to be interpreted as the Roman letters 'P' and 'X', thus creating the Latin word for 'peace', PAX! What could be more appropriate given the historical context of this charter, preserved for us in the astonishing Textus Roffensis.

Select bibliography Charters of Rochester, edited by A. Campbell (Oxford University Press, 1973). Simon Keynes, 'King Æthelred the Unready and the Church of Rochester', in Textus Roffensis: Law, Language, and Libraries in Early Medieval England, edited by Bruce O'Brien and Barbara Bombi (Brepols, 2015), pp. 315-362. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, translated and edited by Michael Swanton (Phoenix Press, 2000).

2 Comments

9/9/2018 07:55:00 pm

I am often to blogging and i really appreciate your content. The article has really peaks my interest. I am going to bookmark your site and keep checking for new information.

Reply

Elizabeth

10/7/2022 08:34:48 pm

I asked my father back when i was a teenager about our ethnicity. He said on his side anglo-saxon. Never knew what anglo-saxon was and until now never even looked into it. I am sorry i had no interest to look into it when i was younger, it is an interesting heritage.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|