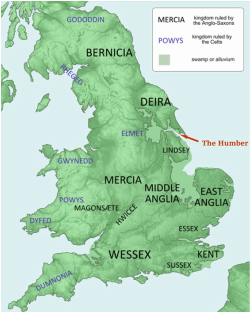

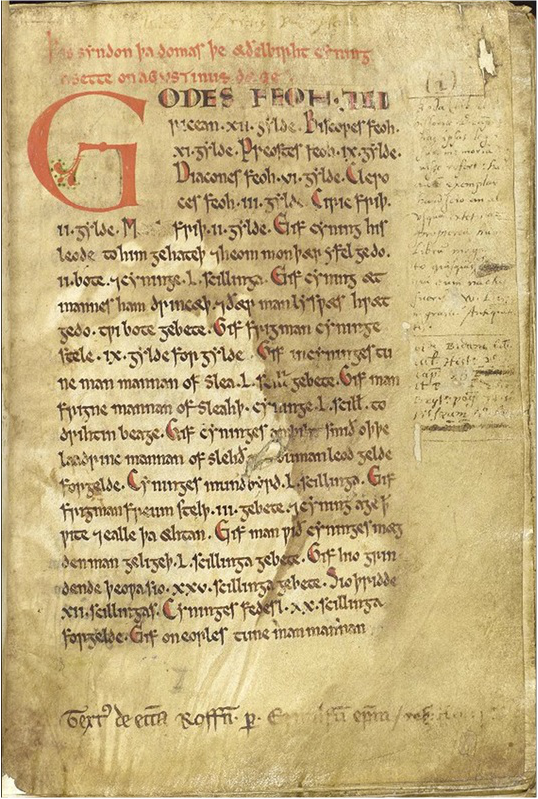

Now, pretty much as soon as Bertie got over his initial reservations about Augustine's team (he made the poor monks sit outside for their first meeting in case they bewildered him with their 'magical arts'), and was persuaded to get baptized, he embraced Augustine's new-fangled writing system and had his laws put onto the page. Yes, English became a language of the book! And, luckily for us, we can glean from Ethelbert's law code some rather fascinating facts about early medieval life in England. So, beloved, here are my first two bitas from Bertie: Rule 17: For the king's feeding [OE fedesl], one should pay 20 shillings. Now, blessed ones, the fedesl was the contribution to the king's sustenance expected of folk as he moved about his realm, which was the custom of kings back then. If a person (think noble or thane, here, rather than a poor peasant-farmer) defaulted on his responsibility to provide for the king, he had to pay a whacking big fine of twenty shillings, probably equivalent to about twenty oxen. Rule 27: If a person slays a freed man [OE læt] of the highest rank, that one should pay with 80 shillings. This fascinates me, beloved, for it refers to a time in England when there was a tripartite system of freed slaves. A læt was indeed a former slave, perhaps some poor captured native Briton, who had been officially set free to make his own way in the world. What's so curious is that back then in early seventh-century Kent, the freed man wasn't quite as free, in terms of social status, as a fellow who was actually born free, a ceorl. Indeed, as we can see from the law above, there was a hierarchy for freed slaves: the life of the highest rank læt was, in terms of the wergild ('man-price'), valued at 80% of that of an ordinary freeman, or ceorl, for whom there was a wergild of 100 shillings; for 'the second rank', we are told, the manslayer had to pay only 60 shillings (60% of a ceorl's wergild); and for 'the third rank', just 40 shillings (40%). Lisi Oliver explains this as probably representing 'a class growing through three generations from a servile status towards the class of freemen, becoming fully free in the fourth generation'. By way of comparison, Oliver explains that in early medieval Frankish territories there are 'records of people being accused of servile status on the basis of allegations that their grandparents were slaves'. Pointedly, Oliver continues, 'such a reckoning never extends to the great-grandparents, so presumably in the fourth generation you have grown free from the servile origins of your kin'. So, there we have it: Bertie's world was one of feeding a hungry king and painfully slow acquisition of freedom for slaves. I am pleased to inform you, blessed readers, that within a few generations (at the time of King Whitred's law, written in 695) Christianity brought to Kent the manumissio in ecclesia, the manumission, or freeing of slaves, which gave instant transformation to the status of freeman. You could still have your slaves, of course, but at least your Christian heart would know that if you did feel like freeing your captive, there was no mucking about with partial freedom: you simply took the fellow to the altar of your local church and have the priest pronounce the manumission. May the Lord be blessed! Works cited: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, trans. Leo Shirley-Price (Penguin, revised edition, 1990), book I, chapters 25, 26 and book II, chapter 3; Lisi Oliver, The Beginnings of English Law (University of Toronto Press, 2002), p. 86 and pp. 91, 92.

2 Comments

The Anglo-Saxon Monk

20/3/2016 01:48:23 pm

Why, thank you beloved Badonicus. I like to share my morsels whenever I can.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|