|

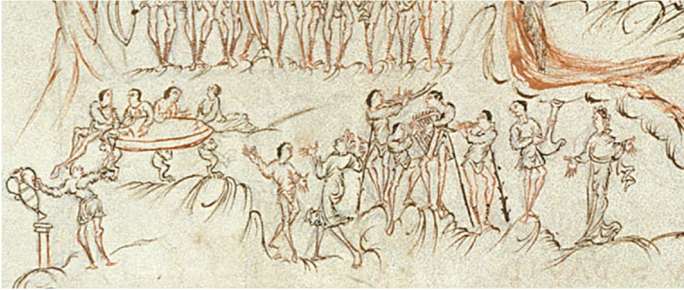

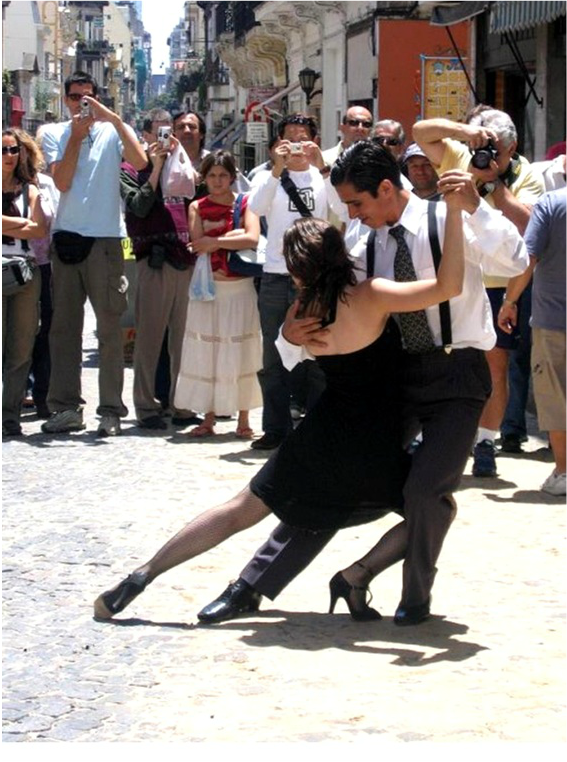

My alter ego and earnest gallivant, Dr Chris Monk, has been describing to me the distinctive delights of Buenos Aires, foremost of which, he reliably informs me, is the Argentine Tango, a dance rooted in nineteenth-century nostalgia and, quite frankly, dripping with debauchery (for which see his postcard below). Not one to deny any soul a well-rounded education, and in desperate need of a tenuous link, I will put aside my propensity for monastic modesty and explore with you, blessed readers, the brief history of dance in Anglo-Saxon England... Now I say brief history, beloved, for really we do not have much in the way of evidence for dance’s place in early medieval English life, which is quite surprising, perhaps, especially as dance seems such a natural expression of the godly quality of joy ... well, doesn’t everyone itch to shake one’s blessed booty now and again? Apparently not if your name was Ælfric. Indeed, that famous homilist of late Anglo-Saxon England described dancing as an impious sin, using the biblical example of Salome, the ‘evil dancing girl’ (Old English ‘þe lyðan hoppystran’)* of Matthew chapter 14, as incontrovertible proof of this. And so it would seem, beloved, at least from Ælfric’s perspective, that if we tolerate even a smidgeon of soft-shoe shuffling at a birth-tide bash, someone is bound to lose his head. Just what kind of parties did Ælfric get invited to, I wonder? Ælfric’s allusion to Salome is not the only negative portrayal of dancing in Anglo-Saxon England. In one of the illustrated versions of Prudentius’ Psychomachia, a fifth-century Latin poem which deploys female personifications of the virtues and the vices, guess who gets to whirl her arms around and strut her funky stuff to distract the warriors? None other than Luxuria, the epitome of self-indulgent debauchery. It seems, too, that even dancing at weddings was a no-no... well, for priests, that is. In the Old English version of the Rule of Chrodegang, clerics are left in no doubt that they should avoid the excesses of nuptial celebrations, 'where obscene bodily movements are displayed in dancing and tumbling' (Old English ‘þær lichamana beoð fracodlice gebæru mid saltingum and tumbincgum’).* I have to say, blessed ones, that all this party-pooping is simply a reflection of the expected stance of medieval theologians. And yet, arguably, it is an emphasis that was misplaced. For just consider the image at the beginning of this post, where the eleventh-century artist of the Harley Psalter captured the essence of joy associated with those desiring to be in the Lord's presence. The drawing illustrates Psalm 41: 5, which states: 'These things I remembered, and poured out my soul in me: for I shall go over into the place of the wonderful tabernacle, even to the house of God, with the voice of joy and praise, the noise of one feasting.' Of course, the Psalmist was employing the imagery of feasting and celebrating as a metaphor for the jubilation associated with being in God's presence. But the Canterbury artist apparently thought it appropriate to illustrate such spiritual joy with a depiction of music and dance. And if it was good enough for him... Now, to master those Argentine ganchos! *Text and translation from Eric Stanley, 'Dance, Dancers and Dancing in Anglo-Saxon England', Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, Vol. 9, No. 2 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 18-31.

2 Comments

Ivana

12/5/2015 06:08:48 am

Well, (Anglo-Saxon) dancing sure beats football :-D. But for some real booty shakin' (and futebol :-)), do visit Argentina's neighboring country. And let me know if you need a translator :-P. The language is even more beautiful than OE, I must admit!

Reply

Chris *The Anglo-Saxon Monk.

13/5/2015 09:52:29 am

Still haven't given up on your idea of Anglo-Saxon football😄. I'm sure I can make another tenuous link! Not been to Braziiiillllll... if I do, I'll be contacting you for Portuguese lessons.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|