Welcome to Mercia, the English Midlands. Or, more precisely, welcome to the laws of Mercia, from which you will discover the answer to the question posed in the title of this week’s morsel of monkish mayhem. (I know I should have used ‘wisdom’, or even ‘penetration’ there, but neither alliterated.) I have a fondness for Mercia, for I originally hale from Derby (Old Norse, Djúra-bý), in the northern stretches of what was once the Kingdom of Mercia – until those wretched heathen Vikings got their hands on it. (Apologies to any and all wretched Viking readers; I know I have a few. The nice ones.)

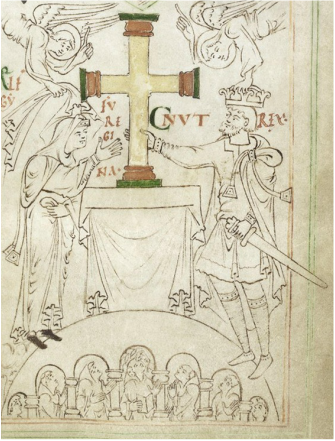

Anyhow, this week, as part of my scribal duties, I translated a short, nine line text from the Textus Roffensis: a fragmentary piece of Mercian law, which is now labelled Be Mircna Laga (‘Concerning the law of the Mercians’), and which probably dates to around the time of Wulfstan, Archbishop of York between 1002 and 1023. Now, as I’m sure you’ve heard, Wulfstan – when not writing his fiery homilies under his pen-name Lupus, meaning ‘Wolf’ (he had, you know, a rather vividly drawn self-image) – liked nothing more than to exercise his law-making inclinations. Not only did he write laws for kings Æthelred (he of the unreadiness) and Cnut (nice Christian Viking king of England), but he is associated with numerous other law-codes, including our Be Mircna Laga. I’m not sure he actually wrote it, but he may have done a bit of emendation. He was that kind of man. It’s a strange text in some ways, a bit old-fashioned even, for it anticipates the wergild or ‘man-value’ of the king, but, as I’m sure you all know, there had been no Mercian kings since the last one, Ceolwulf II (put in place by the Vikings, by the way), popped his clogs in 879. (Apologies for the anachronistic euphemism there.) Anyhow, blessed readers, here’s the text of Be Mircna Laga for you. See if you can work out the answer to the question set at the outset (too long ago, some of you are thinking, I know): A ceorl’s wergild is in Mercian law 200 shillings. [A ceorl (‘churl’) was the lowest ranked freeman, the farmer of my question.] A thane’s wergild is six times greater, that is, 12 hundred shillings. [A thane (or thegn) was a nobleman who was a substantial landowner.] Then, a single wergild of a king is a wergild of six thanes, according to Mercian law, that is, 30 thousand sceattas [or, pennies], that is, in total, 120 pounds. It is the greatest of the wergilds within [the ‘folk-right’ of the people, according to Mercian laws]. [N.B. The latter part of this sentence is missing in Textus Roffensis; it has been reconstructed here from two other manuscripts which also contain this law.] And for that realm there happens to be a further compensation within a king-payment: The wer[gild] is for the kindred, and the king-bot for the people. [Thus if a king was slain, the compensation was two-fold: a wergild had to be paid to the king’s family, and a bot (equal to the wergild) to the king’s people.] You liked that gentle foray into Mercian life, didn’t you, blessed readers? Now, despite not needing to pass a mathematics exam in order to enter the monastic life, I’m still able to handle a bit of basic numeracy (I hope). And I’m sure you’ve already done the sums: The price put on a Mercian king’s life was thirty-six times that of a ceorl, one of those fellows from the lowest rank of freemen who would have farmed his own land. And if you add to that the fact that a slayer of the king would have had to fork out an additional bot (compensation) for the king’s people, then you could argue that it takes seventy-two farmers to make one king. Well, who’d of thought that? In case you’re wondering, beloved ones – what do you mean you nodded off? – it wasn’t only Mercia that had the wergild system. No, indeed, it was used across Anglo-Saxon England, though the amounts for various ranks varied somewhat. Also, though the wergild originated as the amount of compensation to be paid in cases of homicide, it later became associated with fines for a variety of offences, and also as the value of a person’s oath. Some of those other offences included: adultery, theft, accessory to theft, taking bribes, harbouring a fugitive, being excommunicated, violating an ordinance, deserting from the army, incest, sexual assault, breach of the peace, and marrying a widow within a year of her husband’s death – quite right for that last one! Disgraceful! All members of society – we don’t count slaves here, mind you – were protected by their wergild, the sum that would be paid to buy off any would-be feuding relatives should that person be killed. Now what about monks – what’s their value in Anglo-Saxon England? Well, I’ll tell you, my blessed readers, I’m quite furious with the answer – or lack thereof! Look through the corpus of Anglo-Saxon laws, and do we get a mention? Not as far as I can see. Even women get given a wergild in Alfred’s Domboc, but monks? Well we might as well not exist. You can find in the mid-tenth-century Norðleoda laga (‘Law of the Northumbrians’) wergilds for archbishops, which equate to that of a royal prince, namely 15,000 thrymsas (45,000 pence) – even Wulfstan would have been happy with that – and for bishops (8,000 thrysmas), and even for those blinking mass-priests (2,000 thrysmas)! But not a sausage for us monks! Not a bloody sausage! Well, all I can say is that it must have been an oversight. You all know, beloved, how invaluable we monks are, don’t you, I’m sure. Who else is going to wear his scrawny fingers to the bone to bring you such riveting insights into medieval life each week? Who else, I ask you!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|