|

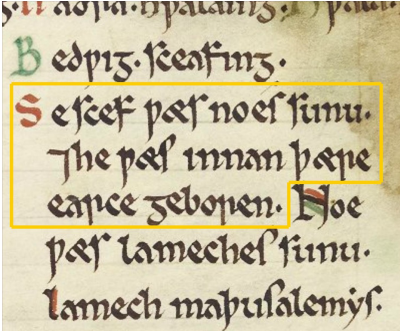

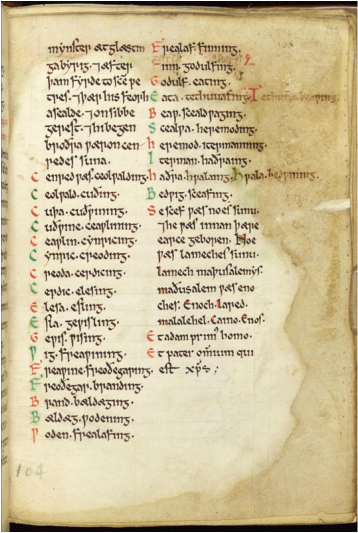

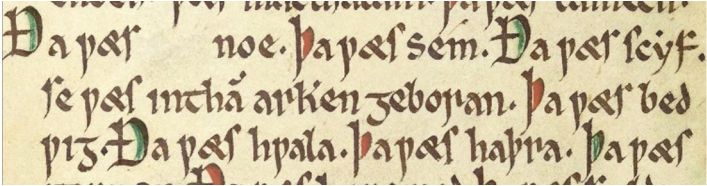

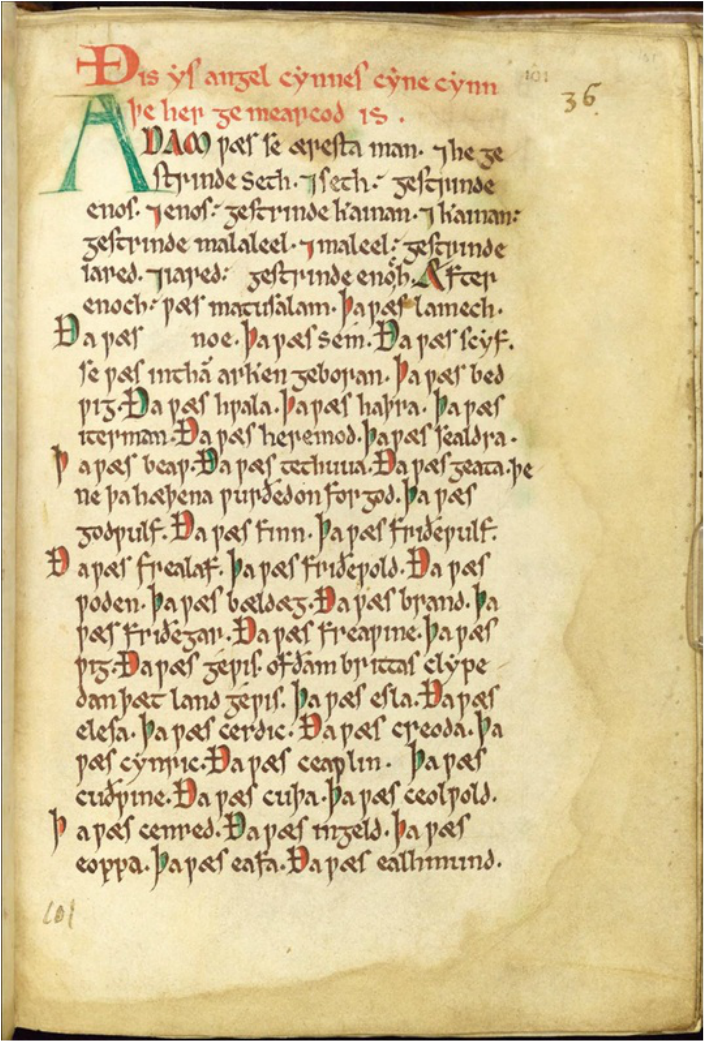

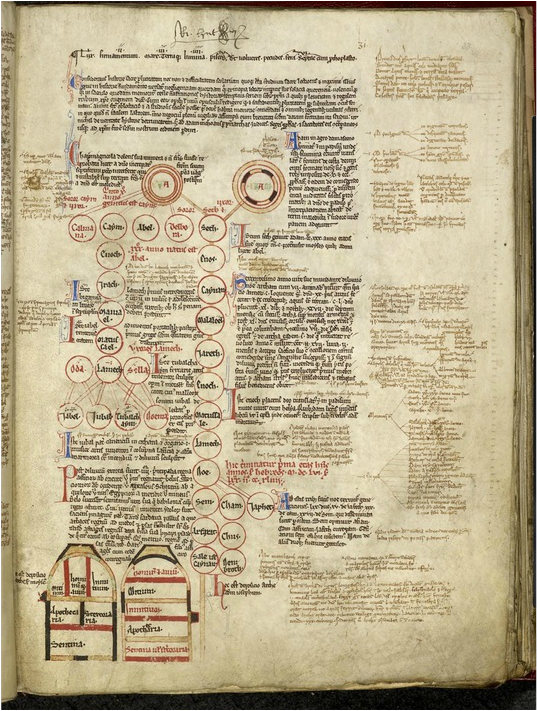

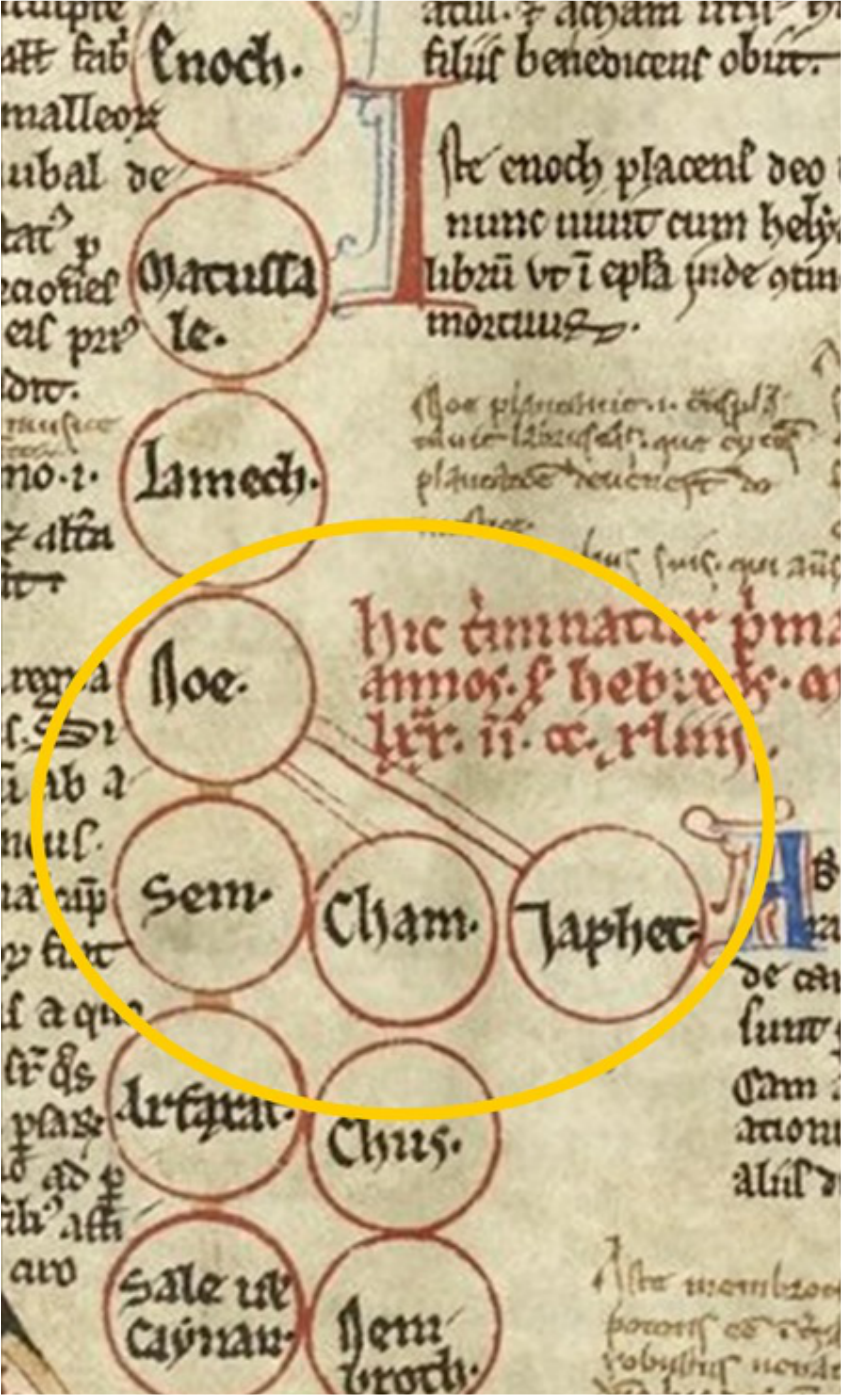

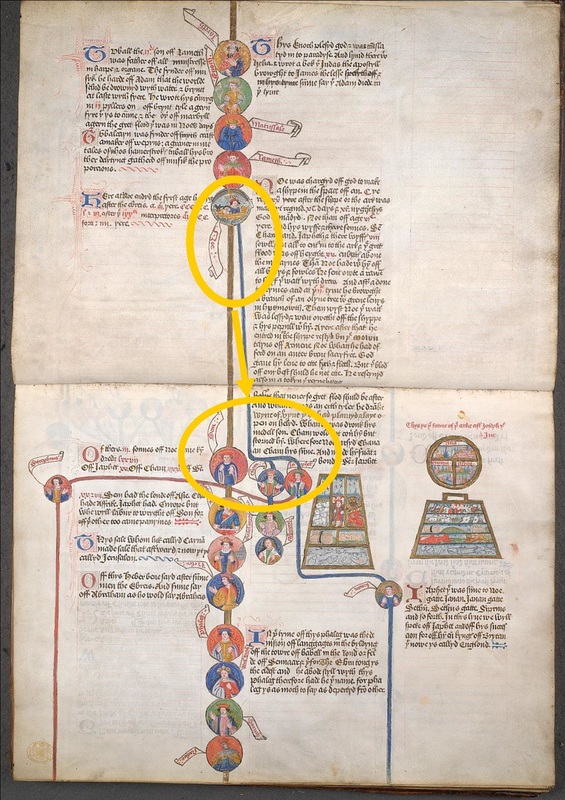

First, by way of providing some context, I should probably point out that the earliest direct evidence for Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies comes from the early part of the eighth century, though it has been argued that they were derived from earlier, pre-literate and pagan Germanic practices, an idea that is supported when we consider the inclusion of many Germanic gods in the genealogies, particular the god-hero Woden. And if you are wondering why pagan gods appear, you should note that scholars have put forward the theory that pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon kings (those of the fifth and sixth centuries) traced their decent from pagan gods in order to set themselves apart from the rest of the population. Eventually, the development of the Wessex (or West Saxon) royal genealogies led to the inclusion of biblical figures, such as Noah, Enoch and Adam, and this probably indicates a similar desire, within a Christian context, to lay claim to divine ancestry. In fact, in the genealogy preserved in the twelfth-century manuscript Textus Roffensis, from which the images above are taken, the West Saxon list finishes with ‘Our Father, who is Christ’. Well, fair enough, I suppose. So to Noah: I'm going to focus now, blessed readers, on the two royal genealogies preserved in Textus Roffensis that show the lineage of the last king of the house of Wessex, good old Edward the Confessor. These lists are essentially updated versions of earlier genealogies preserved in copies of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. If you look at the line above the highlighted passage at the top of this post, you can see that it says, in Old English, 'Bedwig, Scefing', meaning 'Bedwig, son of Scef'; the '-ing' bit means 'son of' or 'descendent of' in Anglo-Saxon genealogies. Now this Bedwig fellow is a legendary figure, but the point is that he is of royal blood, and part of the reconstructed genealogy of King Edward. Next we read that 'Se Scef wæs Noes sunu & he wæs innan þære earce geboren', which word-for-word translates as: 'This Scef was Noah's son and he was inside the ark born'. Yes, blessed ones, Noah and, of course, Mrs Noah found the time for you know what and thus managed to sneak an extra son into their postdiluvian world. And so it wasn't just Shem, Ham and Japheth that walked off the ark as sons of Noah. (Well, I guess Scef probably crawled off.) Now we should observe that since this genealogy is largely a list of 'so-and-so, son of -' entries, then this little amplification is rather significant. Indeed, the genealogist wanted his audience to take note: Our King Edward is related to Noah, he was saying, the blessed and faithful man of God! In other words, by creating an imagined fourth son of Noah, born on the ark of salvation no less, we witness a clever way of building a foundation myth for the English kings of the house of Wessex. And foundation myths should never be underestimated in establishing a sense of nationhood and the divine gift of royal power. The other genealogy of the Wessex kings found in Textus Roffensis is a little unclear about who Scef's father was. Nevertheless, it still serves the same purpose of demonstrating the divine origins of Wessex kingship. Let's take a closer look: Here, on folio 101r, we should first note that this genealogy differs from the majority of Anglo-Saxon genealogies in that it does not start with the most recent king first, but rather commences with the simple statement (starting from the large green A), ‘Adam wæs se æresta man', meaning 'Adam was the first man’. Now, if you were to read Genesis chapter 5 in your Bible (yes, of course you will check this later), you would see that the opening few lines of the Textus Roffensis genealogy correspond very closely to the biblical text. Remarkably, however, though it traces the male line from Adam to Noah, just as Genesis does, it then introduces the apocryphal figure of Scef, here spelt Scyf, who is said to have been born on the ark. Looking at the close-up detail, you can see that it reads: 'Ða wæs Noe. Þa wæs Sem. Ða wæs Scyf. Se wæs in tha[m] arken geboren’, translating word-for-word as, 'Then was Noah. Then was Shem. Then was Scef. He was in the ark born.' So the order in this passage may be suggesting, though it is not completely clear, that Scef was in fact Shem's son, i.e. Noah's grandson, but whether or not this is the case the point remains that Wessex kings could trace their line right back through Noah and even to the first man, Adam. May the Lord be praised for providing such wonderful genealogists! Just as an aside, it is interesting to note that these genealogies do not include every king of a given dynasty. Indeed, it is typical that just one name per generation is provided. The genealogy on folio 101 above actually finishes with six of the more familiar names of Wessex kings, some of whom became rulers of a united England: Alfred the Great (reigned 871-899); Edward the Elder (reigned 899-924); Edmund I (king of England 939-946), Edgar the Peaceful (king of England 959-975), Æthelred (also known as Ethelred the ‘Unready’, king of England 978-1013, and 1014-1016), and Edward the Confessor (king of England 1042-1066), who is usually considered as the last of the kings from the house of Wessex. Now I just want to finish, blessed ones, with the observation that our fourth son of Noah, the mythical Scef, seems to eventually disappear from English genealogies. It's true that William of Malmesbury, England's foremost historian of the twelfth century, still includes him in his Gesta regum anglorum, but not as a son of Noah but as a descendant of another son of Noah, Strephius! Just how many sons did Noah have? My monastic mind boggles! Well, beloved, to comfort your troubled souls, as well as my own, I've provided you below with two later English manuscripts, and as you can see Noah is safely allocated just his three regular sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth. Thank the Lord for that!  This page from a late medieval English theological miscellany has got it right: Noah (Noe) > Shem (Sem) + Ham (Cham) + Japheth (Japhet). Genealogical Commentary, British Library, Harley 658 (England, late 12th century/early 13th century), folio 33r, detail. This image is PUBLIC DOMAIN, identified by the British Library as free from known copyright restrictions. Click on it to go to the source.  Highlighted here from the genealogy of Edward VI are Noah in his boat (top) and his three sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth (below). Genealogical Chronicle from Adam and Eve to Edward VI, British Library, King's 395 (London or Westminster, c. 1511), fols 2v-3r. PUBLIC DOMAIN: identified by the British Library as free from known copyright restrictions. Click on it to go to the source.

5 Comments

James walker

15/9/2017 01:10:31 pm

So the line of descent from Noah is not the same as the line of descent given in the prologue of the The Prose Edda?

Reply

Christopher Monk

15/9/2017 01:57:27 pm

The Edda mentions Noah but does it provide a genealogy listing him? I'm not an expert on Norse literature so can't really comment here with any authority.

Reply

James walker

17/9/2017 04:28:20 am

A vague one, but not as precise as the ones above. The emphasis is on proving a connection to Troy, just mentions Priam's decent from Noah and then starts adding names.

Reply

Christopher Monk

17/9/2017 04:54:37 pm

Thank you, James. I was thinking that the Wessex genealogies were probably not so widely distributed that the Edda author (?Snorri Sturluson) had easy access to them, and even if he did know of them, the language may not have been something he was comfortable working with. It does seem, from what you say, that myth building was as important to him as it was to the Wessex genealogists.

Reply

James walker

18/9/2017 12:52:17 am

Thanks.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|