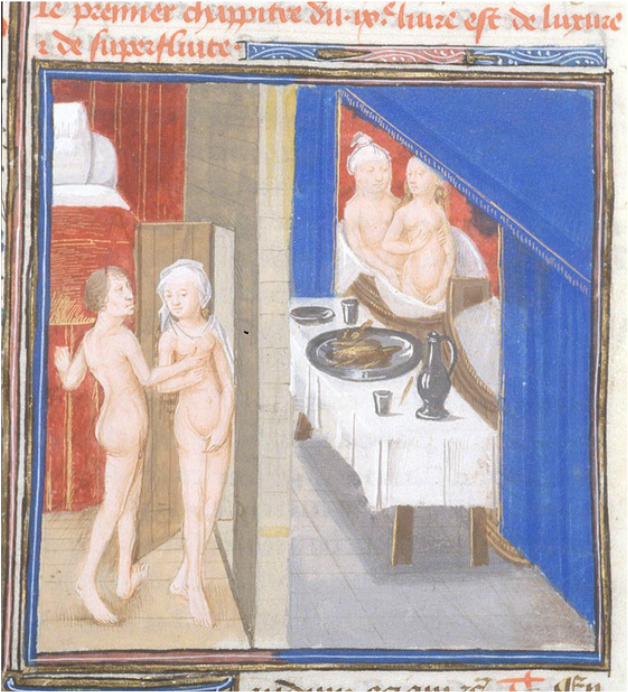

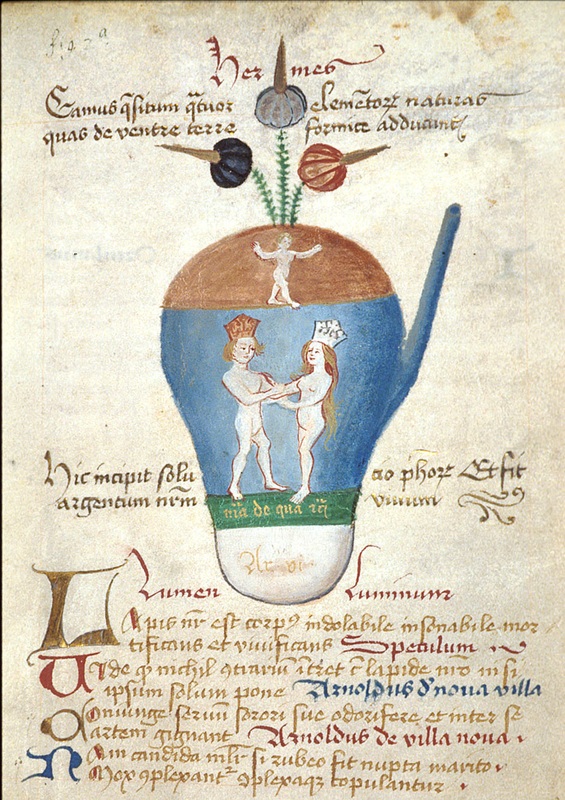

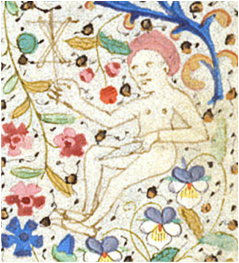

Naked bodies are never incidental in medieval art. There’s always a reason behind the exposure of flesh, and particularly the exposure of genitals – not something with which I have a great deal of experience, blessed readers. That reason, however, is not always the same. In biblical narrative art, for example, the naked body can convey both innocence and sinfulness: there's only a fig leaf between sinless docility and the awakening of rampant desire. In scenes representing Judgement Day, the soul is usually depicted as a naked body as if to emphasize that we’re all naked before the Lord. Nakedness is often linked to shame or humiliation, but the context determines whether we’re meant to engage our feelings of compassion or utter a disapproving Tut! Tut! at the sheer excess of it all. So there are the poor, naked ‘least brethren’ of Christ’s parable, whom we will want to clothe as if they were Christ himself (Matthew 25:36, 40); see the ivory roundel above; and then there are those blatant exponents of luxuria who rightly meet with our severest disapprobation. Outrageous! The most mercurial manifestations of nakedness in manuscripts are those really, really rude marginalia. Just what are we meant to think of half naked men balancing a spindle between their nether regions whilst inhabiting the floral border of a lady’s book of devotion? I jest not! I’m reddening even now at the prospect of taking you there ...

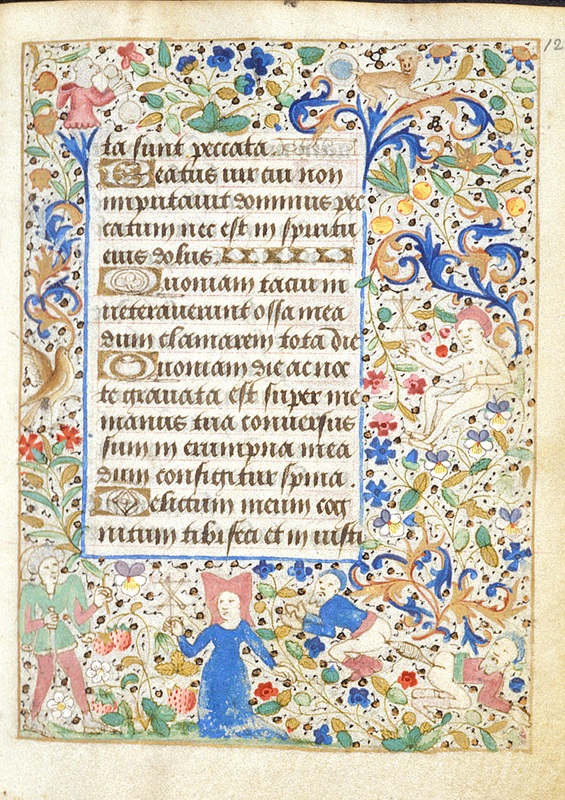

What we need is something beautiful, pure and devotional, to show you a different side to the naked body. What could be better than this exquisite Parisian book of hours? This type of book is often associated with women's private devotion. But look a little closer, blessed viewers. If you dare! Amidst the floribunda border is a vision you wouldn’t wish on the wickedest of Vikings. No, I don’t mean the fellow sitting right of the text. He’s not holding what you think he’s holding. My goodness, you have to stop seeing filth in everything! No, beloved, I allude to the two half-dressed fellows on the right-hand corner of the text, on their knees – still with their socks on, mind you – and engaging in a spot of hide the spindle. But before you hyperventilate through sheer horror, let me just assure you of something. This is the part of the book of hours known as the penitential Psalms, and if you can read a bit of Latin you’ll notice that at the top of the text the word ‘peccata’ (‘sins’) lurks. Yes, this is the part of the book where the reader ruminates over her sins as a precursor to confession. What can be more devotional than to reflect not on her virtuous deeds but on those less than honourable ones that she’s perpetrated? So to help her with that spiritual process the kindly artist has introduced a few images to remind her of the depths of depravity that humans may sink to. It’s quite simple in the end. Now and again it does everyone the world of good to reflect on wanton ways. It refreshes the soul. I wanted to finish this illuminating foray into the world of medieval manuscripts with an upbeat message: With the Lord’s help, Christians can withstand any trial of their faith, even the humiliation of wearing your underwear in public. The alternative message, according to one of my fellow monks (who will go unnamed) is: Less is more.

As you ponder the image above of two faithful, golden-locked Christians, cast before the malevolent Minos, who will heartlessly feed them to the Minotaur, just reflect on those messages. But, blessed readers, if you’re having a problem with my fellow monk’s rather complex message, he has sent me a link to what he terms a visual clue: something to do with a well known marketplace’s merchandise. I have no idea what he’s talking about:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|