|

Notwithstanding the repeated censuring of my betters against impious Heathen ways, I have to admit that Anglo-Saxon charms are, quite simply, fascinating. But then I am a bit of a naughty monk at times. Surviving in a range of manuscripts, the earliest of which are tenth-century, these incantations provide us with insight into the way facets of pagan heritage and culture endured within Anglo-Saxon Christian society. Many of the charms relate to medicine, for curing things like ague, diarrhoea and elf-hiccup – what do you mean elves don’t cause hiccups? Of course they do! Other charms may be sung for protection when you're about to embark on a long journey; others for improving the productivity of your land. Some of the charms, such as the one I’m going to focus on here, have been to some extent Christianised. You may be required, for example, to utter the Paternoster (the ‘Our Father’ prayer) over your neighbour’s nasty black ulcers, or nine times invoke an angel and the Lord whilst spitting on his painful leg – let’s hope you’re good friends! The charm below, which I’ve transcribed and translated from the twelfth-century Textus Roffensis manuscript, is fascinating for several reasons.

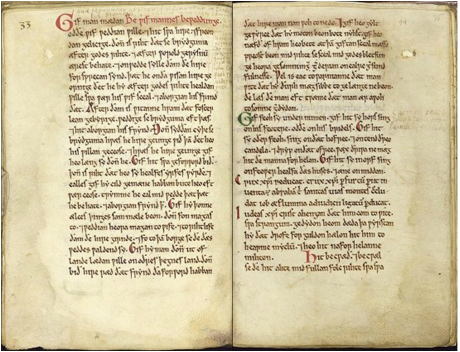

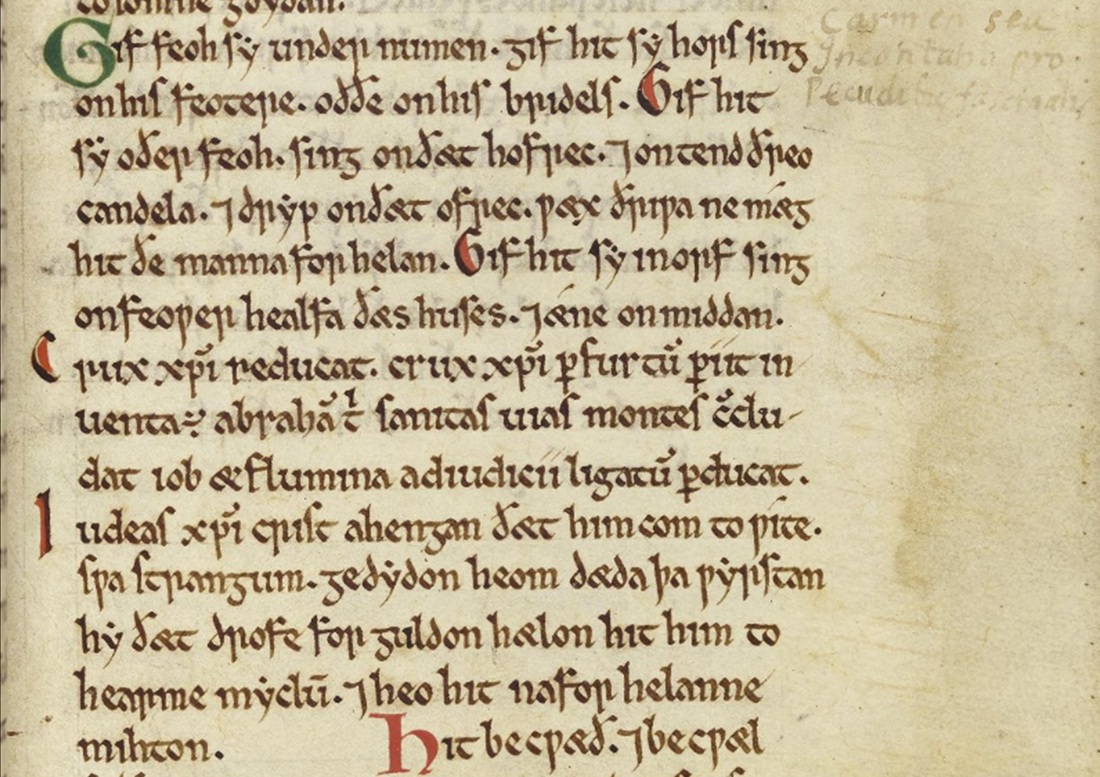

The first thing that is most curious is that it appears amidst a collection of laws. So not long after reading about Northumbrian wergilds (the legal price set against a person’s life) and the correct procedure for betrothing a woman, and just before you find out how to bequeath your valuables in anticipation of popping your clogs (I know! Anglo-Saxons don’t wear clogs: cut me some slack, blessed readers), well, you get directions on chanting a charm in order to get back your stolen sheep. I suppose all these things do relate to personal property in one sense or another – my sincerest apologies to my blessed female readers – so arguably it’s not so daft to see this charm preserved in this context. The second thing that fascinates me is the deployment of pagan traditions – what we might loosely call magic – before any invoking of Christ and the faithful pre-Christian patriarchs actually begins. It’s as if the singing alone is not sufficient: one has to physically engage with the charm process. In this case it’s lighting three candles and dripping the wax three times over the tracks of your stolen animal. One late Victorian scholar explains that this specifically relates to sorcery: the spilt wax will act as magic glue to the feet of your horse or cow, and the lit candles will illuminate the way and expose the thieves. Wonderful! The final point of intrigue relates to the wording of the charm. You see, at least in this case, you’re not simply expected to utter a load of gobbledygook. No, blessed readers, you’re expected to engage your capacity for understanding narrative similitude. In other words, when you read below about the crime of the Jews crucifying Christ – I’m afraid a fair bit of anti-Semitism runs through the charms – you should realise that their deed was not hidden, and neither will the wicked work of your horrid thief be concealed! Rather neat similitude, I suppose. Well, I suspect you want to get on with it, don’t you, blessed readers? I know the pilfering that goes on around here! So, get your three candles, get ready to drip, and chant out that charm! The instructions for giving the charm are written in Old English. The charm itself is a mixture of Latin and Old English. The coloured letters correspond to those in the Textus Roffensis manuscript. [Instructions] Gif feoh sy under numen: gif hit sy hors, sing on his feotere, oððe on his bridels. Gif hit sy oþer feoh, sing on þæt hofrec and ontend þreo candela and dryp on ðæt ofrec wæx ðriwa: ne mæg hit ðe manna forhelan. Gif hit sy inorf sing on feower healfa ðæs huses, and æne on middan. [To be sung] Crux Christi reducat. Crux Christi per furtum periit: inventa est. Abraham tibi [semitas],# vias, montes concludat; Iob et flumina; [Iacob te]* ad iudicii ligatum perducat. Iudeas Christi, Crist ahengan ðæt him com to wite swa strangum. gedydon heom dæda þa wyrstan hy ðæt drofe forguldon hælon hit him to hearme myclum and heo hit nafor helan ne mihton. # TR actually reads ‘sanitas’ (‘sanity’), but this seems to be an error as it does not fit grammatically; ‘semitas’ appears instead in other manuscripts. *The subject and object of the verb are missing in TR; ‘Jabob te’ is used in other manuscripts. Translation: [Instruction] If livestock is stolen: If it is a horse, sing [the charm] upon its fetters or upon its bridle. If it is other livestock, sing over the hoof-track, and light three candles and drip wax three times over the hoof-track: no man may hide it. If it is household property, sing to the four sides of the house and once in the middle. [To be sung] May the Cross of Christ restore. The Cross of Christ was lost by theft: it was found. May Abraham shut up to you paths, roads, mountains; and Job the rivers. May Jacob lead you to judgement bound. The Jews of Christ’s [day] hanged Christ; that came back upon them as a punishment just as powerful. They did to him the worst of deeds, they paid for that with trouble. They concealed it to their great harm, but they were never able to conceal it. If you would like to hear part of the charm text read out loud, click on the link below. A freely accessible edition of the charm texts, complete with translations, is available online. Just click the link below. Go on ... you know you want to leave a comment.

4 Comments

Chris *The Anglo-Saxon Monk

23/3/2015 12:04:13 am

Thanks, Char! I suspect the charms held a fascination for the Norman conquerors. After all, the one I use in the post is found in a manuscriot dating to c.1123. Not only that but the Normans had a Viking heritage themselves and may have therefore been familiar with Norse magic including charms. Off the top of my head, I don't know if the charms survive into Anglo-Norman literature. I will ask a friend of mine ...

Reply

Christopher Monk

8/8/2016 08:37:48 am

Thanks, Kim.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|