|

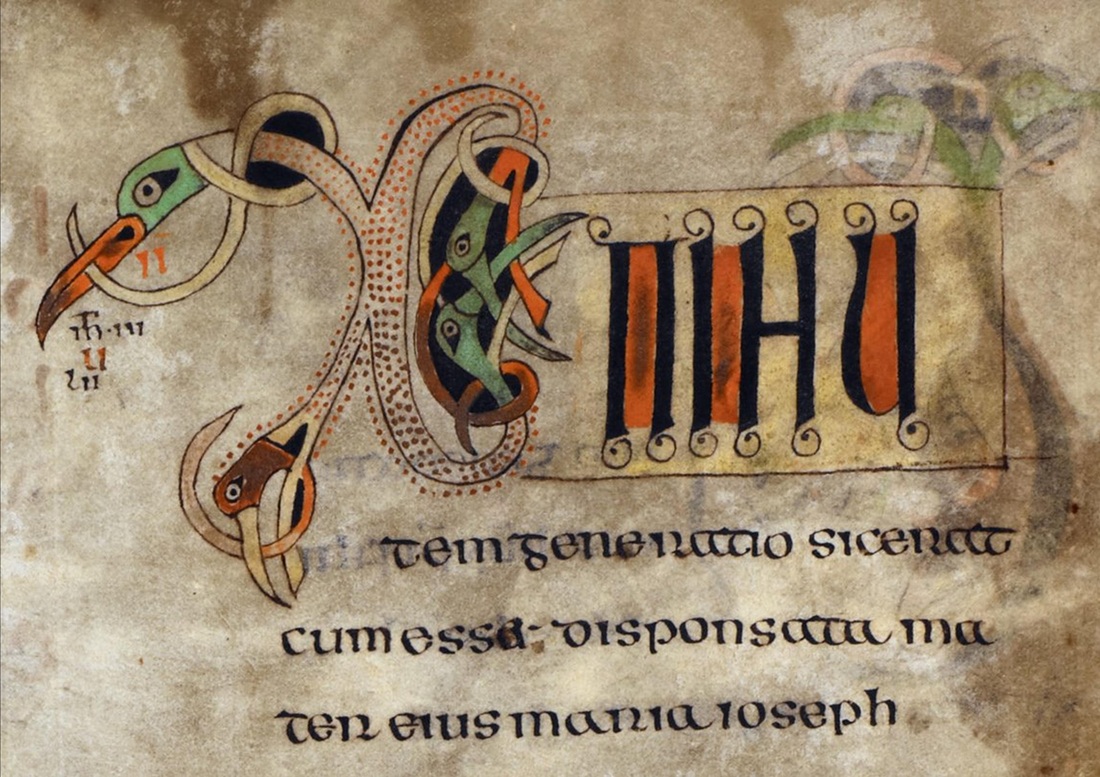

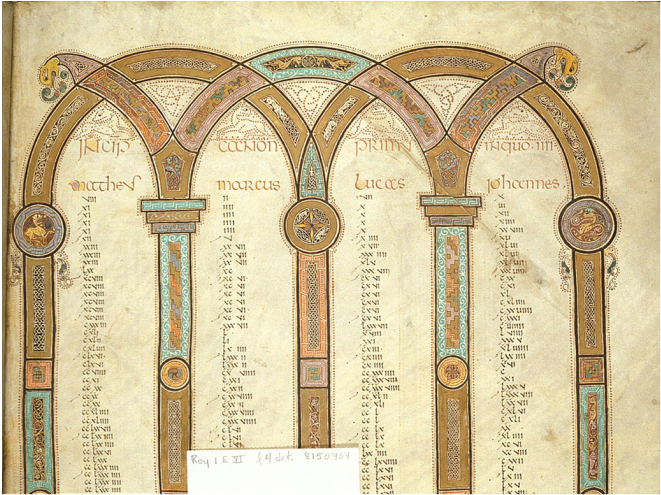

King Alfred. We all know he was Great. Resilient, doughty warrior and subduer of Vikings. Champion of education, lawmaker and military reformer. Not so good at baking, mind you. Let’s just say that he wouldn’t have got his cakes past that devil in disguise Mary Berry and her blue-eyed tormentor Paul Hollywood.* *Non-UK readers: Mary and Paul are the feared judges on one of the UK’s most popular TV shows, The Great British Bake-Off. Now I mentioned just now that Alfred was a lawmaker. Yes, indeed. He wrote the largest piece of early medieval legislation in Old English. Well, he probably got some lowly scribe to work the quill. Someone like me. Part of the reason that his law-code was rather long was because he wrote a preface to it, in which he actually translated several chapters from Exodus, the second book of the Bible. Now, all you blessed theologians out there will know that Exodus incorporates the law attributed to Moses (big white beard and ten plagues of Egypt fame), which includes, at its heart, the Ten Commandments, written initially by the finger of God on a couple of stone tablets (handily knocked up by God, too, I imagine), and subsequently transcribed by more human means onto a human-prepared medium, this following Moses’ smashing of the tablets in a moment of righteous indignation (see DVD image above). By now I’m sure you’ve anticipated me and you realise that King Alfred actually translated The Ten Commandments in his lawcode. Well, actually, he didn’t. Alfred produced The Nine Commandments. Moreover, not content to omit one of God's own big laws, he also took his legislative pruning shears to a couple of the others. Kingly privilege, my blessed readers, kingly privilege. Now as you read his version through, below, and compare it to the version that appears in the Bible, I wonder if you wouldn’t mind thinking about possible reasons Alfred may have had for engaging in – what shall I call it? – a moment of shrewd editing. Please note that I’ve put the numbers of the commandments in square brackets. Traditionally, there are various ways of dividing up the Ten Commandments. I’m following the so-called Septuagint tradition, not because I think it was something Alfred or his clerical advisers were familiar with, but rather because it simply makes more sense to me. It’s my blog, so I’m sticking by this! Alfred’s Nine Commandments. I’ve provided the Old English text for you should you wish to read it. The translation is my own and is quite conservative, tending towards a literal rendering, in an attempt to capture the nuances of the original tongue. [Preamble] Dryhten wæs sprecende ðas word to Moyse and þus cwæð: [Preamble] The Lord was speaking these words to Moses, and said thus: [1] Ic eam dryhten þin God, ic ðe uttgelæde of Egypta lande 7 of heora þeowdome. Ne lufa þu oðre fremde godas ofer me. [1] I am the Lord your God, I who led you out from the land of the Egyptians and from their thraldom. Do not love other foreign gods above me. [3] Ne minne naman ne cig þu on ydelnesse; forðam þu ne byst unscyldig wið me, gif þu on idelnesse gecygst minne naman. [3] Do not call upon my name in idleness; because you will not be innocent with me, if you in idleness call upon my name. [4] Gemun ðæt þu gehalgie þone restendæg. Wyrcað eow syx dagas, 7 on ðam seofoðan restað eow; forðam on syx dagum Crist gewohrte heofenas 7 eorðan 7 sæ 7 ealle gesceafta ðe on heom sindon, 7 hine gereste on þone seofoðan dæg; 7 forðam Dryhten hine gehalgode. [4] Be mindful that you hold holy the day of rest. You will work six days, and on the seventh you will rest; because in six days Christ made the heavens and earth and sea and all creatures that are in them, and rested himself on the seventh day; and for that reason the Lord sanctified it. [5] Ara þinum fæder 7 þinre meder, þa þe Drihten sealed, þæt ðu sy þe leng libbende on eorðan. [5] Honour your father and your mother, whom the Lord gave you, so that you yourself may live long on the earth. [6] Ne sleah þu. [6] You must not kill. [7] Ne lige þu deornunga. [7] You must not lie in secret [i.e. have illicit sex]. [8] Ne stala þu. [8] You must not steal. [9] Ne sæge þu lease gewitnesse. [9] You must not give a false witness. [10] Ne gewylna þu ðines nyhstan yfres mid unryhte. [10] You must not desire with unrighteousness the property of your neighbour. The Ten Commandments, according to the Latin Vulgate (Douay-Rheims translation into English). The red text indicates Alfred’s omissions. Exodus, chapter 20 [Preamble] 20:1 And the Lord spoke all these words: [1] 20:2 I am the Lord thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. 20:3 Thou shalt not have strange gods before me. [2] 20:4 Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, nor of those things that are in the waters under the earth. 20:5 Thou shalt not adore them, nor serve them: I am the Lord thy God, mighty, jealous, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children, unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me: 20:6 And shewing mercy unto thousands to them that love me, and keep my commandments. [3] 20:7 Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain: for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that shall take the name of the Lord his God in vain. [4] 20:8 Remember that thou keep holy the sabbath day. 20:9 Six days shalt thou labour, and shalt do all thy works. 20:10 But on the seventh day is the sabbath of the Lord thy God: thou shalt do no work on it, thou nor thy son, nor thy daughter, nor thy manservant, nor thy maidservant, nor thy beast, nor the stranger that is within thy gates. 20:11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, and the sea, and all things that are in them, and rested on the seventh day: therefore the Lord blessed the seventh day, and sanctified it. [5] 20:12 Honour thy father and thy mother, that thou mayst be long-lived upon the land which the Lord thy God will give thee. [6] 20:13 Thou shalt not kill. [7] 20:14 Thou shalt not commit adultery. [8] 20:15 Thou shalt not steal. [9] 20:16 Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour. [10] 20:17 Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour's house; neither shalt thou desire his wife, nor his servant, nor his handmaid, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is his. Well, what to say? First, that I get Alfred’s truncation of the fourth and tenth commandments. In the case of the fourth one, Alfred just didn't share Moses’ and the Lord’s propensity for fulsomeness. In the case of the tenth, Alfred realised that Moses and the Lord were covering all bases, but he himself just wanted to be a tad more succinct. OK, it does mean that one’s neighbour’s wife is lumped together with the rest of his property; but, blessed ones, such a conflation does somewhat parallel Anglo-Saxon society, though as recent scholarship has pointed out, a wife was not owned in quite the same way as was an animal bought at the market – but that’s for another time. But what about that deletion of the second commandment with its reference to graven things in heaven, earth and sea? Well, perhaps it’s easy to see how this command may have been a bit awkward for an Anglo-Saxon king and his subjects. Just look at the two pictures above showing eighth- and ninth-century zoomorphic design in manuscript art - gospel books, no less. And then there's all that splendid graven zoomorphic jewellery (see below), sculpture and military hardware of the Anglo-Saxon era. I bet Alfred had a few choice pieces. To put it bluntly, Alfred and his people probably had enough birds and beasts to fill the ark! Now I’m quite sure that Alfred, should he have felt inclined, could have put in an explanatory note, had he actually decided to translate the second commandment, something to the effect that this commandment, dear subjects of mine, refers to idol worship, not to your fantastic works of intertwining, biting serpents, dragons and boars. But, he seemed to think the better of it – or his advisors did – and simply let the prior commandment not to love ‘foreign gods’ suffice.

Blessed ones, this reminds me of Ælfric, the great English homilist of the late tenth century, who when thinking about translating the Bible, the Old Testament in particular, tended towards the view that it’s best to leave things out that are too awkward to explain to the average man or woman, as they all tend to be a bit disig (pronounced ‘dizzy’, rather pertinently, and meaning ‘stupid’) when it comes to interpreting the Bible. Now I’m not one to echo the sentiments of my beloved brother Ælfric, and I’d be the last to imply, my blessed ones, that you lean toward the dizzy of this world, though I must acknowledge that my ears have been shamed by one or two rather alarming reports about scandalous behaviour on Friday nights! So, I wonder, what do you think, beloved, of Alfred’s Nine Commandments? Dubious manipulation of the Word of God? Or a case of considerate and thoughtful editing? Go on, you know you want to leave a comment:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|