|

Medieval millers have a bad name. I’m quite sure, knowing as I do, blessed readers, the bent of your minds, that you’ve come across Robin, the drunken, wrestling-loving miller of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (pictured above). I have to say that I only know about this miller's outrageous contribution to the pilgrims’ tales because my alter ego, Dr Monk, told me about it. He lectured on Chaucer at the University of Manchester, you see. But the less we say about hot pokers and arses the better! My own mind is even more troubled, dare I admit, by a real life scandal involving medieval millers and monks. Though the details of the scandal are tantalising sparse, I think you should nevertheless know what waywardness took place in the monastery of Rochester at the beginning of the twelfth-century... just in case it may help you in your journey through life.

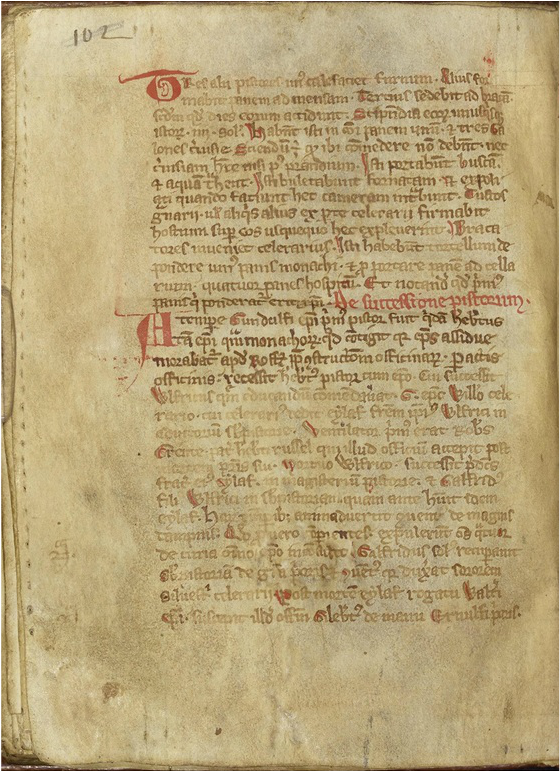

Tales from a customs book According to an account about ‘the succession of the millers’ in Custumale Roffense,# the thirteenth-century customs book of Rochester Priory, the very first miller appointed to serve the monastery and the cathedral was a certain Herbert. He was a tolerably decent fellow, it would seem, assigned by Bishop Gundulf (bishop 1077-1108), no less, who acted as prior and was well known, as the account shows, for his expansion of the monastic workshops including the mill-house. Well, ‘Herbert the miller passed away with his bishop’ and was succeeded by Wlfric, whom the good Gundulf had commended for training when he was alive. Wlfric was not a troublesome miller either, but the same cannot be said for his brother Eylaf, who was initially appointed as under-miller to Wlfric, but then succeeded Wlfric on his death. Here is where things went awry. The account tells us that ‘during these times, the monastery turned its mind to great losses’. These were not spiritual losses but financial ones of some sort. We are then told, somewhat vaguely, that once the brethren discovered the truth they ‘immediately expelled all four from the court’, from the priory, without even consulting the bishop. Now I have to own that it pains me that the monkish compiler of this story was not a little more fastidious in explaining who the ‘four’ were. However, it’s possible to deduce, from names already mentioned in the account, that he was referring to the master miller Eylaf; his son Galfrid, newly appointed as under-miller; the winnower Robert Grente, who worked in the monastery’s granary; and probably the winnower’s son, who went by the name of Herbert Russell. What this dodgy foursome actually got up to is not said. Certainly, the master miller had a lot of responsibility. He would oversee the production of flour from the grain that came into the monastery as food-rent from the various lands in Kent and beyond, owned by the monks. The under-miller, we learn earlier in the Custumale Roffense, was responsible for making sure the right amount of flour was produced: 7 skeps of flour from every 5 skeps of wheat.* Perhaps somewhere along the way, the millers, in cahoots with those aforementioned fellows in the granary, were short-changing the brethren and secretly selling off flour elsewhere. We cannot be sure. What we are told, however, is that one of the fiendish four gets let off the hook. And I know you are simply dying to know why. Well, with a degree of reservation, I give you the remainder of the account: ‘Galfrid alone regained his position of under-miller by the grace of the prior and the convent, because he had led the sister of Sylvester the cellarer.’ Ah, the wonderful quality of grace! But, as you see, my blessed readers, Galfrid was one fortunate man. The phrase ‘he had led the sister of Sylvester the cellarer’ means that he was married to the sister of one of the senior monks of the community (or, subsequent to the scandal, he got married to her). As cellarer, Sylvester was in charge of the stores at the monastery, and would have had daily dealings with the millers, particularly the master miller. It seems he was able to put a good word in for Galfrid to the prior and the rest of the brethren. Let's be kind for a moment: maybe Galfrid was less to blame, or was coerced by his father. But that troubling direct statement that he was married to the cellarer’s sister serves to emphasise, I fear, the true reason for mercy, that Sylvester didn’t want his own sister to suffer on account of her husband’s waywardness. Ah, there’s nothing quite like looking after your own, is there now? Well, back to my own personal grindstone. #All translations from Custumale Roffense are by Christopher Monk who is presently researching the manuscript for Rochester Cathedral. For more information see Projects. *A skep, in Latin eskippa, is half a bushel; a bushel equates to 8 gallons. See relevant entries in Christopher Corèdon with Ann Williams, A Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases (D. S. Brewer, 2004). Go on! Let the Anglo-Saxon Monk know what you think about his post by leaving a comment below.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|