|

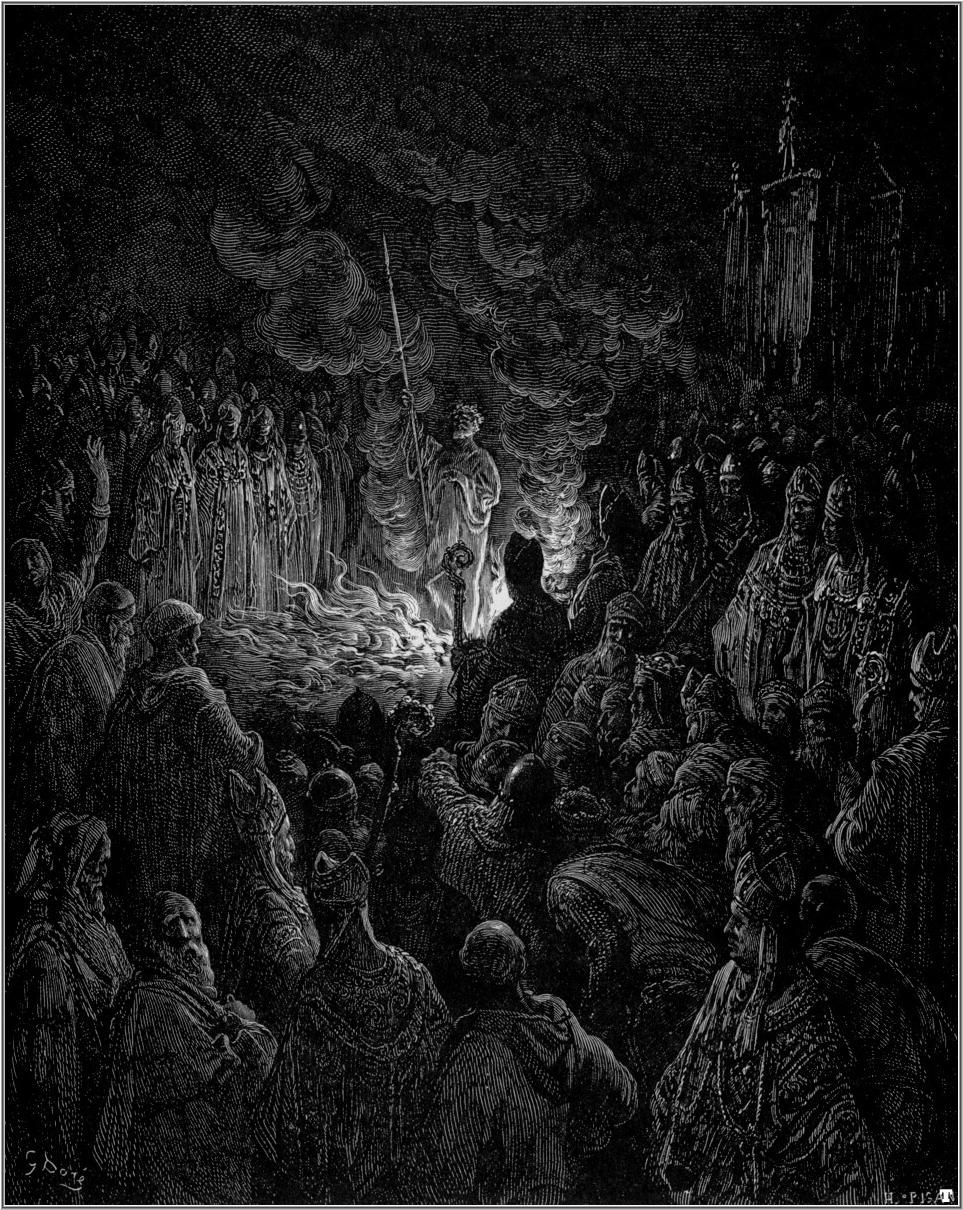

The Anglo-Saxon Monk offers his contemporaneous take on the infamous trial by ordeal in Anglo-Saxon England  The mystic Peter Batholomew undergoing the ordeal of fire, by the artist Gustave Doré (1832-1883). Public Domain image; click on image for the source. The mystic Peter Batholomew undergoing the ordeal of fire, by the artist Gustave Doré (1832-1883). Public Domain image; click on image for the source. Beloved readers, As you may be aware, that other Monk has been busy translating Textus Roffensis, the remarkable 12th-century collection of early medieval laws. Well, good for him. Unfortunatley, whilst I was helping him out with his domestic chores, allowing him to pursue his more scholarly endeavours (we Anglo-Saxon Benedictines like to show a little humility now and then), he decided to abuse me with a snide comment about the backward ways of the Anglo-Saxons. Invevitably, I was provoked (Father, forgive me) and so I asked him to amplify his meaning. He told me he was profoundly disturbed by one of the anonymous laws he was reading in Textus Roffensis, to be specific, the one known as Ordal ('Ordeal') which was probably produced during King Athelstan's time (r. 924-927). How could the Anglo-Saxons, he asked accusingly, have been so backwards and cruel with their justice system? Well, we've always had a testy relationship at best, but that was just adding fuel to the flames! Rather appropriate, now I come to think about it...  The anonymous law known as Ordal (literally 'ordeal', meaning 'judicial decision' or 'judgement') was likely written in the reign of King Athelstan, here shown in the frontispiece of the contemporary manuscript known as Bede's Life of St Cuthbert. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 183, f. 1v. Public Domain image via Wikipedia: click on image for source. "Your trouble," I lamented, "is that you focus on the negative. So, alright," I continued, "back in the tenth century we required thieves and the like to be punished rather severely, and one way of determining whether they were innocent or guilty of an alleged crime was to commit them to the judgement of the Lord by means of the trial by ordeal." Well, blessed ones, he just ranted and raved: "Asking someone to walk nine of their own feet in length with a red hot iron bar in their hand, and then bandaging their hand up for three days before inspecting it to see if it has healed [= innocent] or is full of puss [=guilty], is not my idea of reliably ascertaining if the Lord wishes you to declare somone innocent or guilty!" Alas, he is Monk only by name. He is completely devoid of the understanding of the power of the Lord to intervene in our mundane lives. And so he just continued prattling on about the idiocy of making someone plunge their arm into a cooking pot of boiling water in order to retrieve a stone, and how the same procedure of determining the accused one's guilt or innocence by simply inspecting the wound three days later was astonishingly stupid. I tried to reason with him, blessed ones, I tried. I told him it was all very fairly administered by the priest. All those present as witnesses of the ordeal were in equal number from both sides, supporters of the accuser and the accused. They had all fasted and couldn't go home to their wives that night and indulge in you know what. I ignored, at this point, blessed ones, his snort of derision and his exclammation "What the Hell has that got to do with anything?" and simply persisted with my observations about the spirituality of the ordeal: how the priest spinkled all these fellows with holy water, allowed them all to taste of the holy water, and even to kiss the Gospel book whilst he made the sign of the cross. And, moreover, each man was not permitted to utter a word unless it was to beseech the Lord most earnestly that He should reveal the truth. I was, admittedly, slightly thrown off my discourse when he asked me why they couldn't have just left it at that, why prayer wasn't a sufficient means of asking the Lord to reveal the truth. But I came to my senses and pointed out the obvious, that the Lord needs to see our commitment to the truth. And so concomitantly praying and heating up the piece of iron on the coals and then putting it upon a post for the accused and everyone else to look upon was a satisfactory way of allowing the solemnity of this hallowing to sink in. His retort, that three days of subsequent agony for the accused was more than enough time for the ****ing solemnity of the hallowing to sink into his hand, was, quite frankly, blessed ones, a swear word too far for me. So I simply snapped back that had he been around in those days he would have undoubtedly disobeyed the king's law and would not only have been fined 120 shillings but would most likely have forfeited any hope in the future of being allowed himself to choose trial by ordeal as a means of defending his own innocence! Then I stamped my foot. He just laughed at me and walked off. A moral victory for the Anglo-Saxon Monk, nevertheless. Any how, we did make up later that day when he handed over his translation of Ordal for me to post for my blessed readers. So here it is, dear ones: The anonymous law known as Ordal [‘Ordeal’]: Textus Roffensis, ff. 32r-32v

Translated from Old English by Christopher Monk © 2017 Judgement by hot iron or water And with this ordeal, we are commanding the command of God and the archbishop and all bishops: No one may come into the church – except the mass-priest and the one who shall undertake the ordeal – after the one who carries in the fire, who heats up the ordeal. And, there, measure nine feet from the stake to the finish mark, according to the measure of the foot of the one who undertakes the ordeal. And, then, if it be water, heat it until it rapidly boils; and the cooking pot may be iron or brazen, leaden or earthen. And if it be a single accusation, he should plunge his hand after the stone, as far as the wrist. And if it be threefold, up to his elbow. And when the ordeal is prepared, then from each side two men go in; and they shall reach agreement that it be as hot as we first said; and let equally as many persons of either side go in and stand on both sides of the ordeal, along the church. And all should have fasted and should abstain from their wife for the night. And the mass-priest shall sprinkle holy water over them all; and each of them shall taste of the holy water; and he shall give them the book to kiss and make the sign of the cross of Christ. And no one may strengthen nor lengthen the fire when once the hallowing commences; but lay the iron upon the coals until they die down. Put it afterwards upon the post, and there let not anyone speak within, except that he beseech God Almighty earnestly, so that He the truth may reveal. And let him go forth; and seal his hand; and let it be determined over on the third day, whether it be fully clean inside the seal. And whoever shall break this law, the ordeal on [account of] him shall be void, and he shall render the king 120 shillings as punishment.

3 Comments

Jonathan Herold

15/7/2017 05:31:39 pm

You have the patience of a saint, O A. S. Monk, to endeavor to educate a creature of this skeptical age about the manifest simplicity of 10th-century judicial proceedings (of course, Dr. Monk also had the patience to translate the text, demonstrating that he's not -entirely- benighted). Kudos to you also for posting your meditation on the on the feast of St. Swithun, who, of course, we are told interceded on behalf of Queen Emma when she underwent her ordeal (which, it should be noted, was -not- entirely conducted 'by the book'--or at least not by -this- book).

Reply

Anglo-Saxon Monk

15/7/2017 05:57:07 pm

Blessed may you be, Jonathan Herold (what a shame that isn't an 'a' instead of an 'o' in your second name; it eould make you sound significantly more spiritual, heavenly even)! Quite right about the manifest patience, even that of the other Monk, I concede. And why anyone would wish to malign the gracious Queen Emma with such a scandalous accusation, I will never know. Though you do realise, blessed child, that her naughtiness with the bishop was complete and utter codswallop invented several centuries after her blessed passing. I do like the hot ploughshares elaboration though.

Reply

Jonathan Herold

15/7/2017 06:24:48 pm

Why yes, dear Brother, I am aware that the story that I referred to above is (as we might say in the 21st century) a "truth-y" tale concocted to explain why Queen Emma donated several manors to St. Swithun's church in Winchester (for which generally trusted records have been preserved). What can I say? I'm a fan of Ruth Morse. . .

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|