|

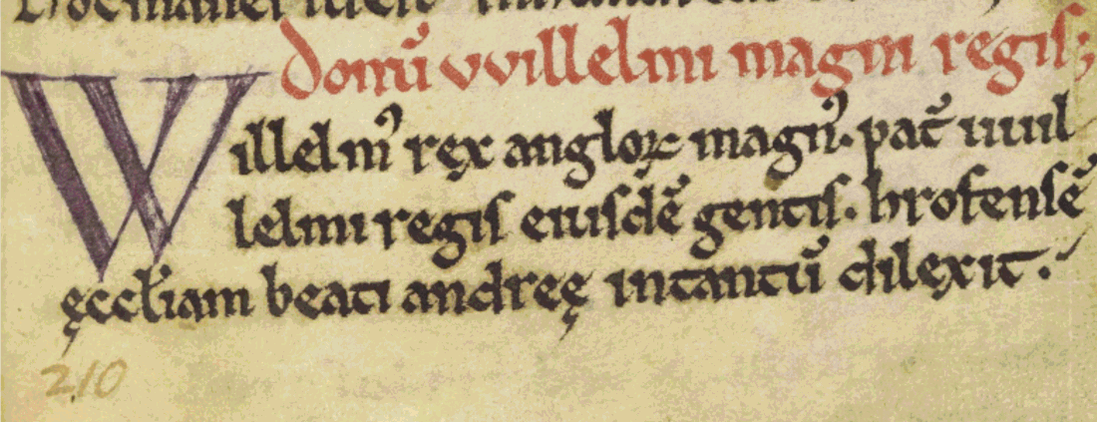

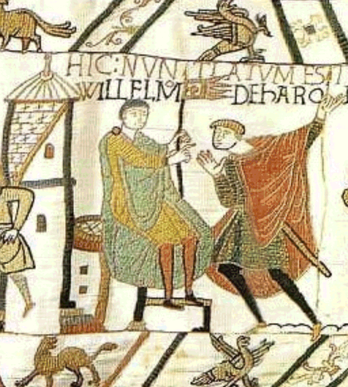

The Anglo-Saxon Monk takes a gander at what King William I bequeathed to Rochester Cathedral priory Blessed readers, Dr Monk has published four more translations from the wonderful Textus Roffensis, all of which you can find links to below. One of these, however, stood out to me: the deathbed bequest of William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087). Being an eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon monk, I am quite sure I don't need to spell out for you why I always shudder at the mere mention of that king's name. But as a time-travelling Benedictine, I must also report faithfully on all matters that come to my attention, regardless of my prejudices. I am nothing if not godly. Let us now swallow out pride and take a look at what the 'great king' bequeathed to the cathedral priory of Rochester. Just to make it clear, that epithet is not mine but was issued by the scribe and his fellow monks, the majority of whom were most likely of Norman descent. Just take a look at the image, below, showing the rubric (the red ink) to the relevant text in Textus Roffensis: Donum Willelmi magni regis ('The gift of the great king William'). And I suppose I should point out the big, purple letter 'W' marking the beginning of his name, and where the text proper begins. You would never guess the brothers were happy with the contents, would you now? Top of the list of goodies was one hundred pounds! One hundred smackers, blessed ones, as some rather disreputable twenty-first century folk I know would put it. Perhaps the later rumours that William regretted his mistreatment of the English are true; and so we need to ask, do we not: was this generosity in reality an act of death-bed penance? Mind you, the Rochester community needed the money because it was not long before the king's son and successor, the even less likeable William Rufus (r. 1087-1100), demanded that Gundulf, the bishop and prior of Rochester (1077-1108), build him a castle, which cost our embattled brother sixty of those hundred smackers. But a profit is a profit, as all good bishop-priors know. The remainder of the bequest is a curious mix of the personal and the ecclesiastical: a royal tunic, a special ivory horn, and a dossal with a silver-gilded frame. Certainly, the bequeathing of garments and textiles was well-known in early medieval England: the Anglo-Saxons liked to give curtains and bedding, and, yes, garments, too.* What the brothers were going to do with the dead king's tunic, however, is anyone's guess. I just hope it wasn't the one he wore at the Battle of Hastings. The 'special ivory horn', proprium cornu eburneum in the Latin, may have looked something like the Horn of Ulph, a carved elephant tusk decorated with silver, 'one of a number of surviving oliphants manufactured in southern Italy in the eleventh-century' ('A Viking antiquity: the horn of Ulph', University of Cambridge exhibition). Now I know the vast majority of you (I'm looking at those of you who don't attend church regularly) are wondering, probably saying out loud, what on earth is a dossal? Well, it is an ornamental hanging placed so as to rise from the back of the altar. At the time of this bequest, this would probably have been a panel of decorated fabric, possibly an embroidery or tapestry.** Earlier in the eleventh century, Queen Emma gave two such hangings, which she had probably made herself, to Canterbury Cathedral.*** Likely something similar was left to Rochester. Well, blessed ones, I am sure you all agree with me that that was quite a generous, and largely thoughtful, bequest from the dying William. I do hope it got him into heaven a little more quickly. Certainly, Gundulf and his monks were appropriately impressed and grateful. In fact, they were so overwhelmed by his benevolence that they established an annual 'festal anniversary' in his name. I wonder if anyone will do that for me when I am gone. Do enjoy reading for yourself the translation of the document, as well as the other three documents. There will be more translations coming in a couple of weeks, so please look out for those. There is a really good one about a later Rochester bishop getting short shrift from a papal legate over his claims to his monks' estates. We all like a bit of scandal, do we not? Update 16 Sept 2022. My older translations of texts from Textus Roffensis for Rochester Cathedral have now been reformatted, so they are no longer available as PDFs but are in webpage format. This means they now have new web addresses. Please bear with me as I correct the links. Please check out the Rochester Cathedral Textus Roffensis page for both my older and newer translations. Notes:

*On Anglo-Saxon bequests, see Anglo-Saxon Wills, ed. and trans. by Dorothy Whitelock (1930; paperback 2011). ** Dossal derives from medieval Latin dossale, which is a variant of dorsalis, meaning 'on the back'; hence the hanging is placed at the back of the altar. From the second half of the thirteenth century, the dossal is associated with the retable, an ornately painted wooden panel. For some beautiful examples, see The Frame Blog. *** See Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg, 'Holy women and the needle arts: piety, devotion, and stitching the sacred, ca.500-1150', Negotiating Community and Difference in Medieval Europe: Gender, Power, Patronage and the Authority of Religion in Latin Christendom, ed. Katherine Allen Smith and Scott Wells (2009), pp. 83-110, at p. 98.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

|